Listen to an hour-long special broadcast featuring a collage of songs, sounds, and remembrances of an Austin legend, from longtime colleagues, friends, Austin musicians, and listeners all over the world.

LISTEN HERE:

Produced and hosted by Art Levy, with assistance from Jack Anderson, Susan Castle, Mike Lee, Taylor Wallace, and Jacquie Fuller.

KUT/X and Austin mourn this one-of-a-kind talent

By Jeff McCord

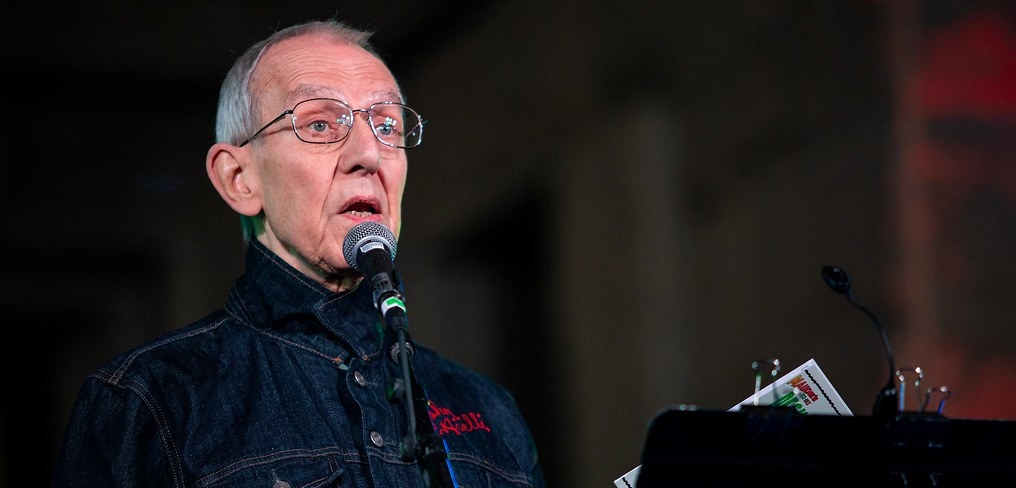

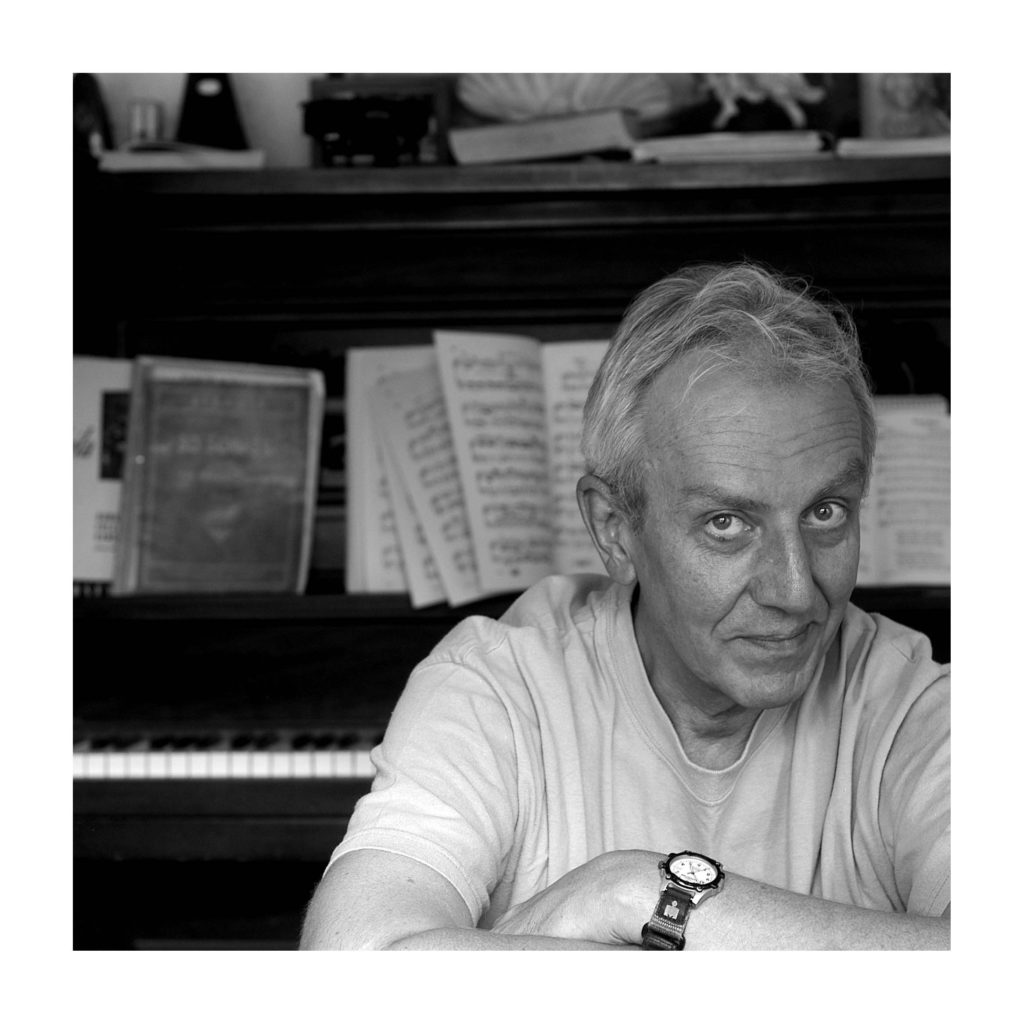

It’s not just that he changed the face of Austin radio, but the way that he did it – by being himself. John Aielli, who passed away July 31, after two years of fighting complications from a stroke he suffered in 2020, dominated mornings on Austin’s airwaves for over fifty years. During that time, he delighted his many generations of fans and confounded an equal amount of others with his eccentricities. There was simply no one else like him on the radio.

John was born in Cincinnati in 1946, but his family relocated to Killeen when he was eight. Because of nearby Fort Hood, John described Killeen as split between well-traveled military sophisticates and “local yokels”. And as a serious vocal and piano student studying under elite instructors, he found himself out of step with most of his peers. Eventually, his talent earned John a piano scholarship with UT Austin. Yet it only covered tuition, and Aielli couldn’t afford the room and board. His parents were both musical; his father was a jazz pianist, his mother a singer. Yet his father clashed with John over his chosen career path. Seventeen and stuck at home, John went looking for work – any work- to earn enough money to leave home and get to Austin.

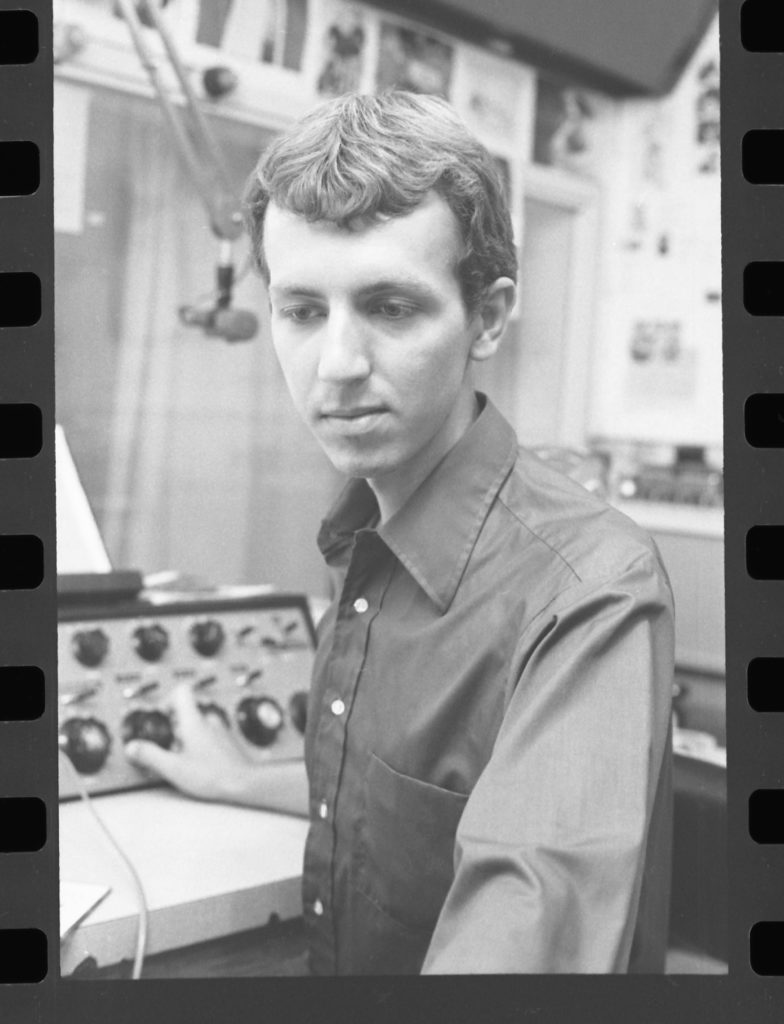

He found it at Killeen’s KLEN, where, hoping for any job, he was, to his surprise, put on air the next day. This forced on-the-job training and lack of fundamentals, a situation that would repeat when John made it to Austin and joined a young, pre-NPR KUT, gave John his many characteristics and quirks. John worked long hours at KLEN, hosting everything from country to rock to classical programs, and he eventually gained absolute comfort behind the microphone. Thrown into a pressured situation – Aielli recalled being alone at the station when news broke of the Kennedy assassination – John did what he already knew how to do: talk. He would adopt a conversational style as if he was doing nothing more than having a private, unguarded conversation with a friend, and he would maintain that throughout his career.

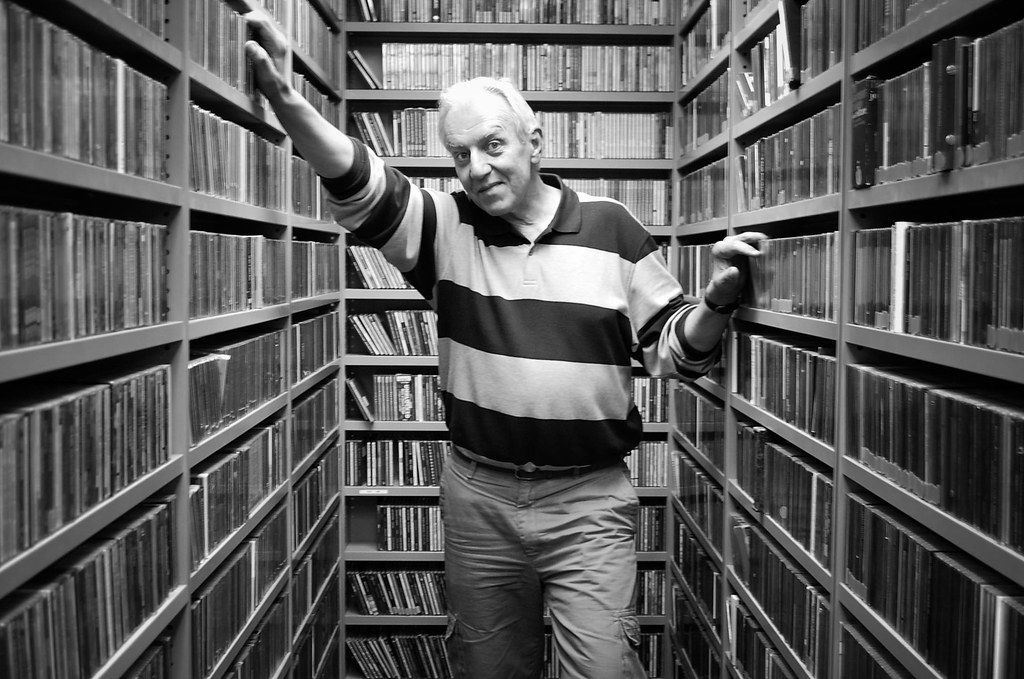

John first began to learn about classical recordings at KLEN, amassing a large record collection. Splitting time between marathon air shifts and pursuing a degree at Temple Junior College, Aielli eventually saved enough money to make it to Austin.

It was 1966, and John was quickly hired by a KUT station just eight years old. His radio experience and affinity for classical music made him a good fit to fill in time between public affairs programming on the station called the “Longhorn Network”. NPR was still a few years off. The news organization incorporated in 1970, ‘All Things Considered’ premiered in 1971. There was no ‘Morning Edition’ until 1979.

By that point, Aielli was already nine years into hosting his morning program ‘Eklektikos’, and it was becoming wildly popular, beaming out to an Austin that was still maturing into something other than a hippie college town. While primarily classical, John was not immune to Beatlemania and the explosion of rock and roll and began to incorporate bits of that, along with folk and pop music into the mix. He was also interviewing guests, going long-form (up to an hour) with many of them. There was no one to tell him otherwise.

When I first started part-time at KUT in the early nineties, the control room was tiny, and the music library was across the building in a locked room. Getting there, finding what you needed, and getting back before the length of a typical song was virtually impossible. And exhausting. So when John would find a guest willing to keep up the conversation, he welcomed the respite. At the time, Eklektikos was six hours long, five days a week – an epic amount of time for anyone to be on air. Aielli had some time to fill. Thus, occasional long silences (“dead air”), longer classical selections, even longer interviews with a remarkable array of talents.

And John’s interview style was basically, “Well, what have you got for me?” He wouldn’t do prep, despite our urgings. He felt – he once told me this – if an interview subject couldn’t interest him, they wouldn’t engage our listeners, either. Some interview subjects, particularly locals who grew up listening to John, and a few touring talents – Judy Collins and Kevin Russell come to mind- were accustomed to his ramblings and played along beautifully. Others froze like a deer in the headlights. He’d ask a famous author about some other book he just read, talk with composers like Philip Glass about growing vegetables, Guy Clark about the shirt he was wearing, Rufus Wainwright about his shoes.

And John would famously obsess on things – words, something he read or spied in a thrift store, and he would spend an entire program randomly playing songs with titles that fit the theme. If he liked the song, he might play it numerous times in a row. If he didn’t, he might yank it off air in the middle of the tune. “Well,” he’d say, that was interesting.” One of his best-known fixations occurred when the film Titanic was released. He just wouldn’t stop playing the soundtrack, often multiple times in a single program. After weeks of this, with listener complaints steadily mounting, I had no choice but to throw the CD in a desk drawer and feign ignorance.

By this point, I was KUT’s music director and tasked with ‘supervising’ John, a man now into his third decade of winning every popularity award there was by doing whatever he felt like doing. At times, he’d listen politely and try my suggestions – focus and shorten his interviews, for example, try not to repeat the same song over and over. Other times he’d be irritable. Either way, the end result was the same – after a few days, it was as if the discussion never happened. He was back to being John Aielli. It was a pattern that would repeat with all his subsequent supervisors.

You’d forget sometimes, and tell John something personal, only to hear it repeated by him on the radio a bit later. He loved to talk, and had no real filter. He was liable to say anything at any time. With one exception: Despite a wide array of friends, John lived alone, and did not easily share details of his personal life. All of us knew he was gay, but it was only much later on in his life when he would openly discuss this. I remember a remote broadcast KUT did in San Angelo many years ago, where John and I ended up in a room doing some late-night drinking. Finally, I thought, I’ll crack some of the Aielli mysteries. No such luck. Here was the irony of John’s life. He was a gregarious extrovert who thrived on conversation with his many friends and co-workers, and with his listeners, yet beneath it all was a private undercurrent of loneliness.

There was a time when Eklektikos tapped the zeitgeist of our city. The arts community thrived on his support. John’s acclaim, ratings and fundraising numbers were all through the roof. Longtime Austinites who grew up on Elektikos stayed with him over the decades. As for those new to town, well, less so. As the decades went by, it was hard for them to understand who this guy was, and the weird things he was saying. Why he was talking about Patti Page in the year 2000, playing songs numerous times in a row, inserting strange classical pieces in the middle of the modern music he was programming? John was fully aware he had his detractors. He proudly displayed an “If You Don’t Tak To Your Kids About John Aielli, Who Will?” bumper sticker above his desk. And we were all aware, too. When out among people, if someone would walk up to me and say, “I have to ask you something,” I knew immediately it was going to be about John.

It’s not an unusual phenomenon. You stay anywhere a very long time and you watch the world change around you, each generation further and further removed, less understanding of who you are or how you got there. John just did it in a public arena. And he had changed, too. He came to Austin hoping to become a professional vocalist. He kept up his studies throughout the seventies, but as his popularity increased, he realized he had stumbled into his true calling. And he thrived on it. He loved his job and was there enthusiastically every morning until health problems began to slow him down. He’d taught himself how to do it all, invented and innovated every step of the way. If it wasn’t how everyone did things, so what? The music and audiences would change, but John was still John, and that, more than anything, was what Eklektikos was about.

I remember, early in my college radio days, gushing on air about a show I had seen the night before and playing several songs by the artist in a row. The next day, I had a note in my box from the program director. It was just one sentence: “Moderation is a virtue.” But it stuck with me.

In our low moments, the air staff, all of us who had come up with at least some degree of direction and training, found it difficult to understand how a man who had been on the air longer than any of us there wouldn’t wear headphones, forcing us to try to give him weird hand signals when he’d forget to turn his guest’s microphone on. Or how he managed, despite years of playing their records, to treat a popular group like R.E.M. as a new artist when their fifth album was released. Or managed to confuse the Hold Steady’s Craig Finn for Crowded House’s Neil Finn, or U2’s Bono for Sonny Bono. Or how our programs scraped for every listener and fundraising dollar while Aielli played silly records of yodeling cows and the acclaim and money poured in.

And then we’d remember: we all loved the guy. His uproarious laugh. His seen-it-all zen. His over-active imagination. The way he’d buy things for people, food, thrift store finds, and bring them to work. The way his weird vocal scales echoed in the stairways. His holiday singalongs. The outrage he’d muster over the latest current event. His absolute devotion to the city’s arts and culture. The gossip he loved hearing and telling. The sprawl of his knick-knacks and ephemera around his desk. The way he drew people to him like a magnet.

We all got frustrated with John at times. The office would buzz with “did you hear what Aielli said today?” comments when he would misstep. But for every one of those comments, there would be another. A wry observation, a way of looking at something commonplace with a renewed passion or enthusiasm, a comment on a song or piece of music you’d heard a hundred times before that made you think about it in an entirely different way. Delivered offhand, in his casual way, these moments would floor me, almost make me pull over my car. “How did he think of that?”, I would marvel. So would thousands of others. John is gone now, but his legacy, the eccentric one-of-kind radio he made for so long, is what we will all remember, the gift he gave to Austin. It’s impossible to imagine this crazy city without him.