In an age where virtually any piece of music can be played on your phone at the touch of a button, young people are buying more and more vinyl records. Why?

By Jeff McCord

Since the beginnings of recorded music, one consumer format has replaced another, each breathlessly promising a brighter future. There have always been holdouts – I have no doubt there were Edison Cylinder purists – but for the most part, music lovers have followed along in lockstep, gobbling up new technologies and trends, and never looking back.

Not any more.

Vinyl record albums were abandoned and left for dead by the record labels when CD popularity peaked in the late eighties. Yet, according to RIAA projections, 2019 vinyl sales will exceed the revenues of CDs for the first time in 33 years (once figures are in). And overwhelmingly, the buyers are under 30.

To paraphrase David Byrne, how did we get here? How is there nostalgia for something under-thirties have never known? Given vinyl’s evolution, there are no easy answers.

Disc records came along in the late 1800s. For a while, they coexisted with Edison cylinders (records were played on ‘gramophones’, to distinguish from Edison’s ‘phonographs’), but by the 1910s, discs had edged out the cylinders. Recordings were primitive, and the thick discs, initially made of shellac, grabbed noise like a magnet. The music could barely compete.

There were various sizes and speeds, but by the 1910s, the 10” 78rpm was the standard, with a limit of two minutes per side. The 12” 78, introduced in 1903, lasted a leisurely 3 ½ minutes. Initially, 78’s were sold in brown paper sleeves. The first ‘albums’ were sets of 78’s packaged with some sort of artwork.

Lots of other materials, from cardboard to plastic, were tried for discs, but it wasn’t until post- World War II that vinyl, with its durability and lower surface noise, came into common use.

After the Depression killed a false start, the 33 1/3rpm 12” long-play album finally came along for good in 1948. The 7” 45rpm debuted around the same time. It would be 1958 before the first stereo records were being sold, a format already in use on pre-recorded reel to reel tapes (yes, that was a thing, especially before the portable 8-tracks and cassettes came along).

And for decades, the vinyl album reigned. Everyone had a record collection. Record stores and stereo shops were everywhere. Equipment got more and more sophisticated. Cassettes and eight-tracks eventually became popular for cars, portable players and mixtapes (and the subject of inane music biz campaigns like ‘Home Taping Is Killing Music’). But vinyl was the mother ship, the ultimate source material. Record prices, initially in the $3 to $4 range, rose higher and higher. By 1981, Tom Petty threw a tantrum, putting his foot down over plans by his label MCA to release his Hard Promises album at a new $9.98 list price. Times were good for the music business, if not for consumers.

And for decades, the vinyl album reigned. Everyone had a record collection. Record stores and stereo shops were everywhere. Equipment got more and more sophisticated. Cassettes and eight-tracks eventually became popular for cars, portable players and mixtapes (and the subject of inane music biz campaigns like ‘Home Taping Is Killing Music’). But vinyl was the mother ship, the ultimate source material. Record prices, initially in the $3 to $4 range, rose higher and higher. By 1981, Tom Petty threw a tantrum, putting his foot down over plans by his label MCA to release his Hard Promises album at a new $9.98 list price. Times were good for the music business, if not for consumers.

They were about to get even better.

Early home computers, connected to nothing except an electric outlet, were little more than glorified typewriters. Yet they were turning data into 0’s and 1’s, and it wasn’t long before that included music. The first commercial compact discs appeared in 1983. At first, early CD players were bulky and expensive, but that would soon change. The format’s promise was enormous.

CDs seemed to solve all the limitations of vinyl we had come to accept over the years. They were lighter, easier to store and transport, not prone to warping, immune to surface noise. The discs had a much wider dynamic range than records – highs went higher, lows went lower – and because they were never touched by anything other than a laser during playback, they didn’t wear out. Vinyl records were limited to about 40 minutes of music. A CD doubled that.

Record companies and retailers saw dollar signs, and from the outset, CDs prices were 1/3 higher than LPs. It didn’t matter; everyone had to have them. Waterloo Records owner John Kunz describes this time as a real “ka-ching” moment for retailers. It was. As one of Waterloo’s early employees, I saw firsthand customers lining up to buy their favorite records over again.

Early CDs, with unreadable artwork shrunk over 50% from their album counterparts, and mastered directly from vinyl, were lacking. Still, CD sales shot up as vinyl sales dropped precipitously. Pressing plants began closing, turntable manufacturers were retooling or going out of business. Throughout the nineties, as CDs improved, most new releases weren’t being manufactured on vinyl at all. People were dumping their vinyl collections wholesale.

Musicians -who always seem left with a smaller piece of the pie of each new format – and vinyl lovers didn’t think so, but these were heady times for the music business. CD sales soared, and wouldn’t slow down until the year 2000. But by then, there were fins circling in the water, and storm clouds overhead.

CD burners, which made an exact digital copy of any CD, were popular and built into many computers, allowing fans to copy CDs for their friends. In the early days of the internet, “friends” grew exponentially. Napster, the peer to peer service launched in 1999 by Shawn Fanning, allowed millions to essentially swap their digital music files for free. Artists like Metallica and Dr. Dre, along with some labels, sued over copyright infringement and shut this thievery down, but it didn’t matter. The cat was out of the bag. Numerous imitators sprung up faster than they could be found and stopped, and as internet speeds grew, and YouTube and Bit Torrents came online, the young and savvy grew up thinking that music was something you found for free online. Record and hi-fi stores slowly began to melt away.

It’s been that way for two decades now. Component stereos have gone into the attic or the trash heap. The music experience for many has come down to badly compressed music played through cheap earbuds or mono Bluetooth speakers. While a few innovative indie record stores have managed to hang on, music retail giants like Tower and Virgin shut down, and other big box stores stopped carrying CDs altogether. Since 2000, CD sales have plummeted 94%. And with no new format in place, the music industry went into a tailspin.

There have been attempts to create a digital revenue stream – Apple’s popular iTunes store (launched in 2003) and line of iPod’s was among the first. But it didn’t reverse the trend. Only in the late 2000s would the industry find another stable way to monetize music, through the advent of subscription streaming services (there are many, but the biggest, Spotify, came along in 2008). While not necessarily profitable themselves, even though only paying artists a tiny sliver of their revenue, the services’ income has managed to stabilize and even grow things business-wise.

Even with their drastic fall, CDs are still being sold, but younger music fans aren’t the ones buying them. Over the past decade, physical music sales are on an upswing. But it’s vinyl, a format left for dead in the nineties, that is leading the charge. And the buyers are predominantly under thirty.

When I first started to hear that vinyl was selling again, it made sense to me. I have a large collection [though much to my regret, I sold about half of it during the CD boom, records that would now take four times as much to buy back, even if I could find them]. But I’m not one of those who ditched my turntable and stereo. I really never stopped playing records, even when new ones were not being made. For me, it was aural muscle memory for a format I grew up with, and an association for when and where I bought my favorite albums.

Plus, I love the sound of vinyl. Battered by the ‘everything loud’ creed of modern digital mastering, the best-sounding records seem more authentic, musical and alive. I was an early adopter of the convenience of digital music and its vastly superior specs. But on a decent stereo, something seemed lost in translation.

When I was a kid, records were relatively inexpensive and easy to find at any local record store. Listening to these albums years later, I ‘m transported back to my initial excitement and discovery, to what made me so passionate about music in the first place.

But seeing the young demographics involved in the revival, it occurred to me that NONE of these reasons really explained what was going on. In a day and age where virtually everyone uses streaming services that can pull up almost any song on their phone, when two decades have gone by for many without a physical format or even a stereo, what is causing them to suddenly seek out vinyl?

Former Austinite Don Radcliffe, who owns the used record shop Ella Guru in Atlanta, has his theories. “I guess there’s some people that are doing it for the same reason that we did. You’ve got to put a little work in. You’ve got to spend money rather than just finding it for free and putting it on a hard drive, when basically all you have to do is press a button to make it go away. And some people enjoy the the the tactile part of it, the cover. Vinyl records don’t hold near as much music as a CD. So, in those 35 minutes or whatever, why did they pick those songs? Why are they sequenced that way? You know, the same dumb stuff that attracted us to it. And they read credits and they look at who produced it. What else did they produce? Or they discover some musicians on it. Jesus, this guy is awesome. What other bands was he in? The web starts getting spun a little bit and they’ve got to figure out where everything sort of fits.”

Spencer Smith, 30, who bartends and is a projectionist at the Alamo Drafthouse, has been a vinyl fan since age fifteen, when he first asked his parents for a record player. “At the time, I was listening the way most kids do, downloading from the internet, mostly illegally. I think something about the process felt kind of cheap to me. I could download a thousand records a day, but I would never really listen to them. You take a kid and put him in the middle of a candy shop. There’s no clue where to go first. Something about having the music physically and listening to every song in order really appealed to me.”

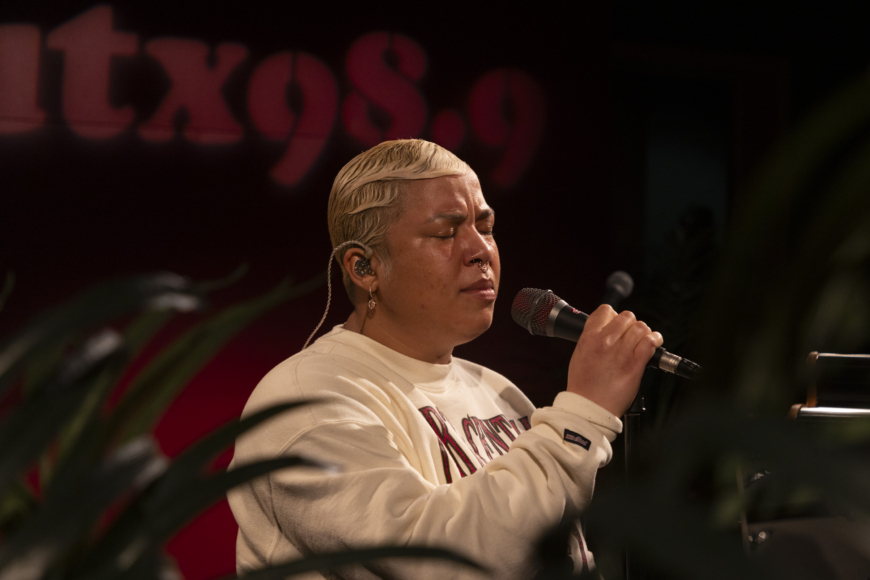

“I didn’t start collecting records until I was in college,” KUTX host Taylor Wallace, 29, confesses. “I’m from a small town and didn’t know anyone who did. My parents grew up in the CD era. This was around 2009-2010, right when it was getting popular. All my friends, and these guys I wanted to date, they all had record collections. I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is a thing.’”

John Kunz recalls it being about fifteen years ago when he first started seeing a vinyl sales uptick at Waterloo. Superstar artists with clout, perhaps disappointed in declining CD sales, began demanding limited runs of vinyl – because they could. Labels obliged. Stores generally had one shot at ordering them. But their scarcity added to their appeal.

Kunz remembers the advent of Record Store Day, started by a coalition of independent record stores in 2008, as the moment while vinyl sales really began to rise. “The record labels were giving every Circuit City, Borders, Best Buy and Wal-Mart exclusive bonus tracks. And we [independent record stores] were all here saying, you shouldn’t be messing with the core product. That’s really confusing to the customer. Give them the exclusive as a digital download. But we want an exclusive release on vinyl.” [It’s a tradition that continues to this day. Record Store Day 2020 is on April 18th.]

While Austin still mourns the loss of classic record stores like Inner Sanctum and Sound Exchange, it is fortunate to have some pre-2000 survivors – Waterloo and Antone’s Records – and numerous other excellent post-2000 vinyl shops across town, several of them also offering a wide assortment vintage hi-fi gear, including End Of An Ear, Sound Gallery, and Breakaway Records.

Breakaway, which is exclusively analog, is co-owned by Gabe Vaughn and Josh LaRue.

“It’s not a lot of people;” LaRue tells me. “Many young people are music fans but only a few go down the vinyl road. Some people get the nostalgia thing – they saw their parents play records or they saw it in a movie or something.”

“And for some people, it’s an identity. I remember being younger and wanting to be about something, you know, like I’m a collector.”

Not everyone who buys vinyl is a collector. Collecting most anything never makes a lot of practical sense. [If you want to know if you’re stricken with this malady, take this simple test. Read this recent New York Times article about the Archive of Contemporary Music’s collection of three million albums needing to find a new home. If your initial thought, like mine, was “I wish I had room for that”, you’re a collector.]

Other buyers seem to be, um, more casual. All three record store owners who spoke to me told me versions of the same story. When they asked certain young vinyl buyers how they were playing their records, it turns out – they weren’t. They owned no turntable at all.

“I have a conversation on a pretty regular basis where people are, you know, buying dollar records.,” explains LaRue. “Or even more expensive records, you know, like ten-dollar, 15 dollar used records. And I’ll ask about a turntable or what they’re doing right now. And they’re like, oh, I don’t have anything. So some kind of disconnect going on there. Maybe they’re listening to them at a friend’s house or maybe it’s easier to spend 20 bucks on used records than to spend hundreds of dollars on a turntable, or 400 dollars on a system. I get that. But I don’t understand what they’re doing with the record.”

“There are some kids that are buying them just to put the artwork on the wall,” says Kunz. “Others say I just want to support that artist.”

But these are odd exceptions. For the most part, young vinyl buyers are playing and enjoying their records. On what, though, varies widely.

It’s easy to see why. Turntable manufacturers have sprung back in action in the wake of the vinyl revival. But good precision gear, like the best of today’s vinyl pressings, can be expensive. One of the things fueling the vinyl revival was the emergence of low-cost, kitschy all-in-one record players made by companies like, er, let’s call them ‘Crosbys’. [To be fair, the same company also makes high-end turntables.] And at Waterloo, where they sell the portables, they are careful to describe them to customers as “the perfect record player for your eleven-year-old’s slumber party.” Nonetheless, some buyers aren’t getting the message.

Austin musician Scott Riegel, 26, who became a vinyl enthusiast at the age of 12, describes his beginnings. “My dad grew up in the ’70s, and had a pretty decent record collection for a guy his age. He bought me this cheap, all-in-one “Crosby’ player. So I started listening to stuff on that, and then I posted about it on a forum. They started roasting me for playing records on that cheap all-in-one turntable. So I dug my dad’s stereo setup out of the attic.”

Without such treasures hidden in the attic, though, the process gets tougher. New vinyl hopefuls go from “Hey, Siri, play the Beatles” to being told about all they need to make a physical record play. “It’s understandable,” says Kunz.”They start looking at a turntable and we ask them what they’re going to be pairing it with. They don’t know what a receiver is. An amplifier. When they say they’ll be hooking it up to their A V system, you say, does it have a phono input? And they don’t know what that is. Speakers? You got to have all this stuff.”

“There are people who just buy like a pretty lousy record player because they see it at Target. And there’s no way that sounds good,” says LaRue.

Yet despite the steep learning curve, many have pulled it off and are enjoying their vinyl on good gear. LaRue sees that happening. ”It’s hard for me to know what percentage, but there’s certainly a good number of people who are looking for quality pressings of records and buying real stereo equipment to hear it on. They’re aware of and paying attention to how good it can sound.”

LaRue describes vinyl’s audible aura. “There’s a certain human error vibe that’s very relatable. You know, it’s like a lot of hip hop. After a while, they started making the beats not totally perfect. They would still use a click track and drum machines and samples and all that, but they would make beats slightly more human-sounding. And I think people, even if you don’t notice it on a conscious level, [vinyl] feels a little more natural, it feels a little groovy.”

Yet vinyl’s distinct sound, a chief reason why long-time vinyl enthusiasts have put up with storing and lugging around record collections for decades, doesn’t come up as much among younger record buyers.

“I think people have a point when they say it,” says Spencer Smith, who estimates he owns two to three hundred vinyl albums. “But I question how true that is. People say there’s better quality or it sounds warmer. I’m inclined to say that since the streaming services are so good, it’s a hard argument to make.”

It’s true that new bands and releases, in this day and age of recordings being mastered for compressed mp3’s, streaming and earbuds, don’t really shine on vinyl. Yet this seems to be primarily what’s selling at Waterloo. Kunz estimates 75 to 85% of his new music is being sold on vinyl. “When they were doing all the digital mastering to put vinyl on CD, they were using an analog master person. The reverse was true going back the other direction. It was someone that didn’t know what they were doing, and the mastering was fucking everything all up.”

LaRue hears it, too. “Now that most people listen to super-compressed digital files on earbuds, they try to make recordings sound good for that format, which is hard. A lot of music that’s recorded digitally, straight into Garageband, can sound really great, except that it’s a different type of music and a different type of recording. It’s very different from the 60s and 70s, you know? There are so few pressing plants anymore. They have so much demand. They’re getting digital files like that are just getting emailed to them. They’re doing stuff as fast as they can. And the quality control has dropped.”

“I think a lot of the appeal for me and for some young people getting into records for the first time is the stuff that was, you know, recorded and pressed in the 60s, 70s, even through a lot of the 80s, when the goal was to make it sound good on a record on a turntable. Even like early hip hop and dance, it was about deejays and clubs like with sound systems and turntables, everything was geared towards that.”

Which might explain why this era is now selling again. Don Radcliffe loves getting rare records in his store, but the 60’s and 70’s hit recordings are his go-to records for young buyers. Nestled among the new releases in Waterloo’s top vinyl sellers is Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, an album that looks exactly like it did when it was released with an $8.98 list price in 1977. It sells for $24.99. Waterloo keeps a six month supply on hand.

There’s a lot of mystery around the vinyl revival, but it does seem to be bridging generations. Parents and grandparents are gifting their kids their favorite albums, and discovery is starting all over again.

John Kunz imagines a father surprising his son or daughter, telling them “In the back of my closet, I’ve got all the Led Zeppelin records. All the Supremes records or whatever, they are owned by grandma. And suddenly grandma is not this little old lady that doesn’t know shit. She’s the coolest person on the planet. Music is doing exactly what it should do. It’s bringing people together.”

Years without physical product, with fans essentially renting music from streaming services, seems to have left listeners hungry for something more tangible. They like streaming for musical discovery, but it’s not enough.

“I like owning the album,” says Taylor Wallace, “Especially when it’s about local bands, because that’s money in their pocket. And I like shopping. It gives me another reason to go out and buy something.”

In a world of multiple entertainment options, ownership seems to be adding value back for music fans. “I think that people pay more attention,” says LaRue. “They are literally invested in it. People like going to the store and buying something that they’re into. It’s not just food and clothing. This is something they really like. ”

Hanging out in record stores used to be the path to finding new music. For some, at least, that seems to be true again. But it’s not just the buying. It’s the process itself.

Scott Riegel finds it transporting: “A nice Zen day off for me is putting on a record, hanging out with a cup of coffee. You’re listening to it and appreciating the subtleties of the sound.”

“I think the physical motions of taking a record out of a jacket, putting in on, you know, the whole process, because it’s harder,” says La Rue, “makes somebody much more focused on the music. For me, it still does. My family, everyone has Spotify and all that. And but we play records all the time. My kids pay more attention, you know, just because they pick a record out, they go to the shelf. There’s a lot more to it. It’s a deliberate physical act that takes multiple steps to hear the music.”

Whether it’s the process of obtaining or playing vinyl, one thing is clear – there is no single answer to what is driving young people to buy and play a format that began a century ago. It’s puzzling for a lot of reasons. But discovering music, bridging generations, rediscovering the value of the album, listening more intently – all are big positives for music fans, artists and the industry. And for whatever reason it is happening, everyone seems happy that it is.

I was at a party over the holidays where my friend Andy was playing records. I started discussing the vinyl revival with him and asked if he had any explanation as to why young people were turning to a format that effectively ended before they were born. Without saying a word, he walked over to his records, pulled out his copy of ZZ Top’s 1973 album Tres Hombres and opened it up. And there it was, staring me in the face. An eye-popping 24”x12” gatefold photo, a technicolor burst of cheesy tex-mex gluttony. We both just stood there grinning. Maybe it really is as simple as that.