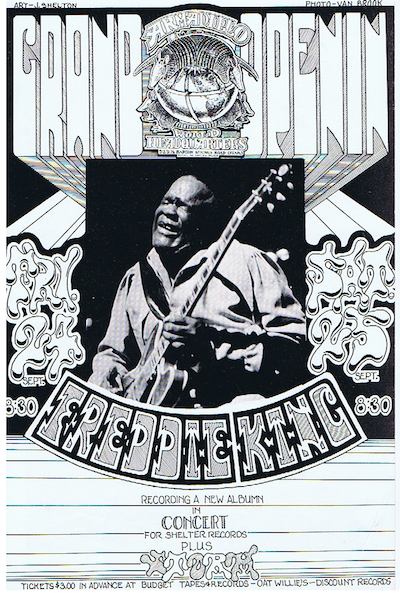

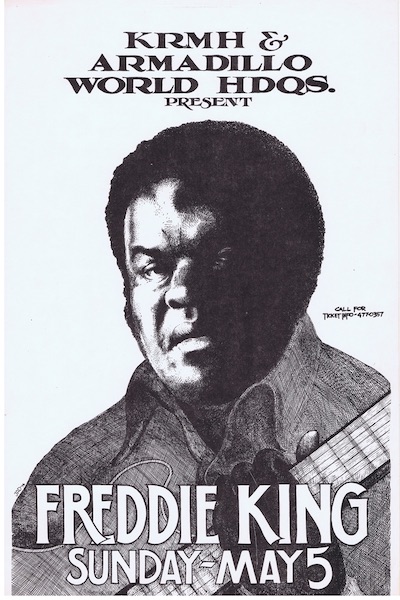

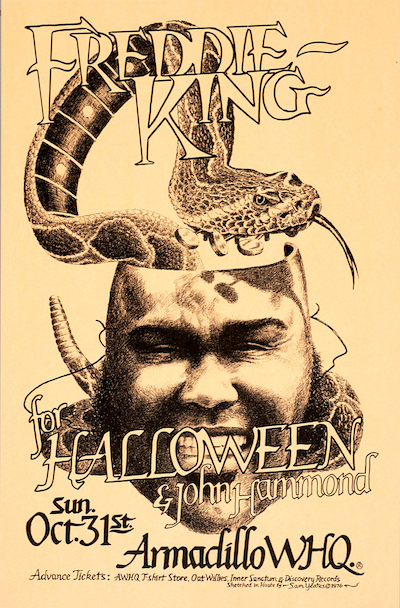

Poster by Jim Franklin. Image courtesy of Austin Museum of Popular Culture.

by Art Levy

When it opened in August of 1970, the Armadillo World Headquarters was not set up for success as a music venue. For starters, the space was a cavernous, former National Guard armory—no air conditioning, no seating, certainly no acoustic treatment or high-end sound equipment. The building could fit an audience of thousands, but there were no local artists with that big of a draw. As a city, Austin was something of a cultural afterthought, a sleepy town centered around the state government and the University of Texas.

“We would sit around for hours trying to figure out who we could get to play there that would actually break even or make money,” remembers Mike Tolleson, the Armadillo’s in-house lawyer. Cut off from the national touring circuit, Tolleson had to build connections with New York and L.A. booking agents, “just getting them to recognize [the Armadillo] as being a viable facility in Austin, Texas in those days when bands didn’t want to come to a redneck area.”

Freddie King soon changed that perception. Born in tiny Gilmer, Texas, King grew up in Chicago and immersed himself in the blues scene, first sitting in with Howlin’ Wolf’s band at the age of sixteen. He developed an idiosyncratic take on blues guitar, combining Chicago’s electrified sound with a Texan wildness influenced by Lightnin’ Hopkins and T-Bone Walker. His booming voice traded punches with his searing lead guitar licks, sounding like a force of nature.

Yet King’s first national exposure came on an instrumental. “Hide Away” was a Frankenstein of a song, combining ideas from Hound Dog Taylor, Jimmy McCracklin, and even the theme to the popular TV series Peter Gunn. Released in 1960, “Hide Away” hit number five on the R&B charts and number 29 on the Billboard Hot 100, becoming one of the first blues songs to cross over to a white audience. A few years later, Eric Clapton covered the song, which helped spread King’s sound to British audiences.

Throughout his career, Freddie King was on the road nearly three hundred days per year, supporting acts from James Brown and Sam Cooke to Led Zeppelin and Grand Funk Railroad. In the late ‘60s, his constant touring first brought him to white Austin audiences. The Vulcan Gas Company was a counterculture-run club intended to showcase burgeoning psychedelic rock acts like the 13th Floor Elevators. But it also became home to a passionate and dedicated blues scene, featuring national stars like King along with Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Big Mama Thornton and others. When the Vulcan closed, its sensibility seeped into the Armadillo. The staff hoped blues giants like King could help pay the bills and turn the Armadillo into an in-demand live music destination, for fans and musicians alike.

King soon became an Armadillo favorite. He played the venue thirty-four times, in the top ten of most appearances of any Armadillo act. “Freddie was tremendous. Freddie was wonderful. Freddie was so giving,” Bruce Willenzik, an Armadillo employee, told the Armadillo Oral History Project in 2010. “Every time we were really in bad financial straits, call Freddie and get him in for two days and pack this joint and make some money.” Those shows were legendary for a lot of fans. “It seemed like he’d always show up [in] August, when it was just the hottest time of the year,” Frank King said in 2010. “It was just brutally hot, and he would play a smokin’ [set]—just two hours straight.” Under the Armadillo lights, sweat poured off Freddie King’s towering frame, but he always kept that sense of Chicago cool. “I remember him always being dressed up in a suit, big lapel,” Susan Rose recalled. “Once he started, I don’t think he stopped for a long time…I was mesmerized. You really couldn’t do anything but listen.”

For Micael Priest, one of the Armadillo’s iconic poster artists, Freddie King had almost supernatural abilities. “In the middle of a gigantic thunder and lightning storm, he hits this long, leaning note. Everything gets real quiet. And then the biggest clap of thunder the world has ever seen, right on the end of that note when it was so quiet…[and] the entire audience just levitated! Actually left the ground.” In 1975, King sought to capture this intense Armadillo connection. He recorded part of his album Larger Than Life live at the venue, electrified by a full horn section and thousands of screaming fans. “At the Armadillo he was a bigger star than he was anywhere else in the world,” Willenzik recalled, and “the audience at the Armadillo made him feel 100 miles tall.”

While King’s incredible shows earned sold-out crowds and awed fans in Austin, he also helped spread the Armadillo far and wide. “Freddie was probably our number one promoter,” says Eddie Wilson, the venue’s proprietor until the mid-1970s. Everywhere he went, King told musicians about the devoted audiences he was finding at the Armadillo. It was King who first convinced superstars like Leon Russell to take a chance on this funky venue in Austin. “Leon signed Freddie to Shelter Records,” Wilson explains, and King told Russell “you’ve never heard an audience like this, and forced Leon to come to play [the] Armadillo.”

One of the biggest markers of the Armadillo’s success: the staggering amount of beer the venue sold. “We were selling more Lone Star than any other outlet other than the Astrodome,” artist Jim Franklin remembered in 2010. The beer brand teamed up with the Armadillo for a statewide radio advertising campaign. King voiced a number of these spots and even recorded the jingle “Nights Never Get Lonely,” a Lone Star-themed blast of blues-rock that became a regional hit thanks to the extensive airplay.

Yet King’s years of travel soon caught up with him. He developed stomach ulcers and pancreatitis in 1976, dying at age forty-two. King left a big hole at the Armadillo. He helped the venue stay financially solvent in the turbulent early years, connecting the club’s black blues roots to its later national ambitions with some of the most memorable shows in the Armadillo’s ten years. “Whenever there was a blues act that played the Armadillo, they would play ‘Hide Away’ as sort of an homage to Freddie King,” Armadillo fan Michael Wimer remembered in 2010. Jim Franklin visualized his impact with a gruesome but accurate painting: King, deep in blues ecstasy, with a bloody armadillo shooting out of his heart. But the biggest nod to King’s outsized legacy? The Armadillo World Headquarters’ quasi-official slogan: “The House That Freddie King Built.” Austin wouldn’t be the “Live Music Capital Of The World” without the Armadillo’s success, and the Armadillo couldn’t have succeeded without Freddie King.