NPR | By Jewly Hight / Published March 21, 2023 at 11:16 AM ET

Lawmakers’ agendas would ordinarily be too stodgy a subject to interest drag performers. So it was an ominous sign last December when Eureka O’Hara opened her “Big Mawma” music video with a clip of a news report about Republicans from her home state of Tennessee fixating on “deceptive claims about young transgender children having gender-affirming surgeries.”

“Well, it’s the truth,” O’Hara reasons over Zoom about her decision to use that current event reference as a 13-second intro. The rest of the clip depicts transgender coming-out narratives — partially inspired by her public acknowledgement of her own trans womanhood the same day as the video drop — and the allyship of plus-sized, cis women over her track’s militantly anthemic electro-pop.

Over the first three months of 2023, the Republican supermajority in the Tennessee Legislature has fashioned the alarmist narrative about trans youth that served as a grim backdrop for O’Hara’s on-screen defiance of transphobia into a raft of restrictive legislation. Those lawmakers have been pushing through a sweeping collection of bills that crack down not only drag shows, but may imperil the performing careers of singers and instrumentalists who don’t do drag at all, but happen to be nonbinary, transgender or gender-nonconforming, while also eroding the rights of trans youth, adults and their families in crucial education and health care matters.

The first two to clear the Tennessee Senate and House and get signed into law by Gov. Bill Lee deny minors access to gender-affirming health care and ban “male and female impersonators” from taking the stage on public property or where anyone under 18 could be present, effectively categorizing drag as sexually explicit adult entertainment that’s harmful to minors. On top of those measures, Republican lawmakers are advancing a bill that will further limit drag by requiring professional performers to obtain permits, another allowing government employees to refuse to solemnize same-sex marriages on the basis of religious beliefs and a third that would legally define gender as a male-female binary prescribed by a person’s anatomy at birth. Still another under consideration would prevent insurance companies that cover gender transition treatment anywhere in the U.S. from working with Tennessee’s Medicaid program, TennCare.

Tennessee is hardly the only state where Republicans are erecting such obstructions around the lives of LGBTQIA+ residents. That’s nearly become a national obsession among conservatives this legislative session. Similar drag bills are in the works in Kentucky and elsewhere; Arkansas, Florida, Utah, South Dakota, Alabama and Mississippi have also already put a stop to gender-affirming care for youth; North Dakota, Montana, Oklahoma, Georgia, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Missouri, Ohio, West Virginia and Texas are debating their own legislation, often targeting not only transgender health care, but athletics too.

Still, Tennessee’s actions are notable for how aggressive they are — according to the Human Rights Campaign, they outnumber those of many other states — and for how they’ll impact Nashville’s lucrative and widely watched music industry. Given how many of country’s leading women have served as judges on RuPaul’s Drag Race — roughly half a dozen and counting — it’s not surprising that there are murmurs of concern about the fate of drag in certain corners of the country mainstream. But the implications for musicians of many stripes means the worry’s spread all around. It could disrupt numerous other scenes: those populated with young, queer voices; or those inclined toward activism; or those that pride themselves on their independence. Pop stars could be deterred from bringing their tours to Music City, or going there to make use of its infrastructure, work with its seasoned pros or brush up against its history. It’s hard to imagine an entertainment town thriving when LGBTQIA+ expression, a prime mover in popular culture always and everywhere, gets constricted. Nonbinary roots singer-songwriter Adeem the Artist forecasts a drain of talent and influence: “The strength of Nashville is going to only diminish from here out,” they say, “especially as the world develops beyond it.”

A lot left open to interpretation

Republican leaders who championed the new drag law have repeatedly insisted that their fundamental motivation is protecting children, not attacking the queer community, and that the statute’s purview is clear and easy to enforce. Tennessee Senate Majority Leader Jack Johnson, who drafted the anti-drag bill, tweeted that the bill “gives confidence to parents that they can take their kids to a public or private show and will not be blindsided by a sexualized performance.”

But legal experts like Kathy Sinback, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Tennessee, point to dangerous ambiguity in lawmakers’ choice of wording. The fact that the statute names “male and female impersonators,” rather than drag queens and kings, she notes, opens the door to conflating the art and craft of dressing in drag with the everyday embodiment of transgender, nonbinary or gender-nonconforming people, music-makers included.

“It is definitely broad enough to include trans people,” Sinback observes. “I think the intent is to be able to enforce it against anyone who [legislators] feel is not complying with the gender norms that they think they should be exhibiting. Anyone who’s dressed as a sex that they were not assigned at birth is a ‘male or female impersonator’ in their point of view.”

Another aspect of the law Sinback thinks is left far too open to interpretation is the settings to which it applies. Though Republican lawmakers made clear that curbing Pride festivals in their communities is a specific priority, she says, the way the statute’s written casts a much wider net: “It’s so broad as to be able to be enforced in most places, depending on who wants to enforce it and their beliefs. It can be basically any venue. It could [apply to] somebody’s house if [the performance] could be seen through a window, potentially, by a minor.

Attorney Abby Rubenfeld, who specializes in LGBTQ family law and testified against the bill in front of a House committee, warned that it will certainly be challenged as unconstitutional. “A law is unconstitutionally vague criminal law if it doesn’t give people specific notice of what behavior is prohibited,” she explains, seated behind her desk in a law office housed in a century-old, converted brick bungalow.

At odds with the entertainment industry, past and present

At least so far, pushback from the entertainment sector on economic grounds hasn’t really fazed The Volunteer State’s Republican legislators. Not when a proprietor of Nashville’s two most prominent gay bars, Play and Tribe, and its popular, touristy transportainment venture, The Big Drag Bus, appealed to a House committee to take into account the revenue generated by those businesses. Nor when more than 200 companies, among them leading country management, publicity and marketing firms, booking agencies, publishing outfits and record labels, signed the Tennessee Pride Chamber’s letter to the governor. Its closing plea, that Lee veto the drag bill because it’s “bad for our economy” and “our soul,” went unheeded.

The same politicians who are portraying the drag law as a triumph of traditional family values over a perceived new moral threat appear equally uninterested in the tradition of drag even in their own state. “It’s not like drag just popped up in 2023,” says historian Philip Staffelli-Suel. He’s found newspaper accounts of forms of it that predate the Civil War, at circus and theater engagements that catered to middle-class families, no less.

Staffelli-Suel can reel off names of numerous drag-hosting establishments that have coexisted with various eras of country tourism in Nashville’s downtown entertainment district since the dawn of the 1970s. In the ’90s, a country drag spot right on Lower Broadway was where Reba McEntire first enjoyed her consummate impersonator, the late Coti Collins, who eventually landed a role in a pyrotechnics-aided production stunt on McEntire’s tour. As of 2021, a side street less than two miles away bears the name of Bianca Paige, a drag queen who was a local leader in raising funds and awareness at the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis.

When the initial two bills became law in early March, a coalition of artists and industry professionals, convened by Allison Russell, immediately began plotting to put on shows benefiting organizations that work on the behalf of LGBTQIA+ Tennesseans, like Tennessee Equality Project and Inclusion Tennessee. They were able to book 16 drag queens and kings and nearly two dozen musical artists — Mya Byrne, Brittany Howard, Jason Isbell, Hayley Williams, Julien Baker, Joy Oladokun, Autumn Nicholas, Maren Morris, Brothers Osborne, Adeem and more — for Monday night’s Love Rising concert at Bridgestone Arena. The impressive lineup not only brought together an array of pop, indie-rock, Americana and country performers, some of whom move in overlapping orbits, but not all of whom would ordinarily share the same stage — it counted as the state’s largest gathering to date of LGBTQIA+ people and allies who oppose the legislation, reinforcing for the thousands that packed the arena that they, too, speak for The Volunteer State.

Show organizers were in a hurry to beat the April 1 deadline, after which the drag ban goes into effect and an event like that, in front of an audience of all ages, would likely be out of the question for the Bridgestone. The arena’s one of many prominent Nashville venues that allow minors at least some of the time. The venerable Ryman Auditorium, where Ashley McBryde recently brought her cleverly downhome and colorful Lindeville Live musical theater piece for two consecutive nights with drag queens in the cast, is another.

“We have to protect these people too”

Drkmttr Collective, the smallest venue to sign the letter to the governor, wears its teen-friendly status on its exterior. Adhered to the window of its strip mall storefront is a sticker of a cartoon angel beaming goofily over the words “all ages.” “When we say ‘all ages,’ ” clarifies Olivia Scibelli, one of the owners, as she jiggles her keys in the lock and coaxes the door open, “we do mean all ages. It always has been such a safe space for any human being, regardless of how you look or who you’re with. As long as you’re not hurting anybody, you’re welcome here.”

Jewly Hight

Drkmttr has already survived longer than many other independent, all-ages spots in Nashville, thanks to its resourceful, DIY approach and commitment to adapting to meet local needs; besides shows, they’ve hosted community organizing and reading groups and mutual aid efforts.

Scibelli looks slightly perplexed when asked what portion of the shows they’ve booked might defy the new law. She has no estimated percentage to offer: “For us, it’s more of just, like, all the time.”

“I mean, we have trans entertainers in here all the time,” she elaborates. “We have nonbinary people, people who dress in drag. We are here for the community in whatever capacity, whether it’s to blow off some steam at a metal show or to have a safe space to walk a ball and have some drag.”

The new law won’t change that, she vows. “But I also want to maintain the idea that we have to protect these people, too. So if we had a drag show, I don’t want to just get the drag queens arrested. You have to stand in front of them and protect them.”

“So, arrest me,” she challenges with a burst of mischievous laughter. It’s gallows humor, but a scenario she may have to seriously consider in the days to come.

“It’s because it affects me as a human being.”

At the Bluebird Cafe, the storied home of the most Nashville of all performing formats, the writers’ round, seasoned songsmiths take turns singing unadorned renditions of their compositions for multi-generational crowds in an atmosphere of rapt, reverent listening, enforced when necessary by shushing staff. Cidny Bullens played the final March 2020 round there before the pandemic shutdown. Now he’s worried about legal prohibitions against him returning to share his songs. “Does this [new law] mean that I can’t play the Bluebird because I’m a trans person in Nashville?” he asks during a Zoom interview, letting the question hang heavily in the air. “The way it’s worded, it’s a draconian [law]. Basically, it might as well say that you have to dress as your birth gender.”

Bullens has been in the music business for half a century. Early on, he grew acutely aware of the scrutiny of certain performers’ outward gender expression in certain climates. He knew from age 3 that he was a boy in a girl’s body, and dressed accordingly. That continued when he got a big break in the ’70s singing backup for Elton John in stadiums, and labored to build a solo career with a rousingly kinetic stage presence, his style “to swing a Les Paul and jump off pianos and not be frilly.” Back then, the industry still viewed him as a woman, and the androgyny that suited him personally didn’t boost his professional image the way it did some cis male rockers of the era. “It was difficult to move through the world as who I was, but I couldn’t be anything different,” he recalls. “I lost record deals because I wouldn’t dress like a woman. I lost professionally because I wouldn’t conform.”

By the time that Bullens transitioned in 2011, he was 61 years old and had drifted away from his rock origins toward deep involvement in the Nashville singer-songwriter community, clicking with similarly searching veterans of country and Americana renown. The Refugees, his folk trio with Wendy Waldman and Deborah Holland, simply adjusted its old way of billing itself as an all-woman lineup. Though he had never been much for pointedly topical writing, he began to embrace autobiographical work, giving documentary interviews and shaping a one-person show.

Sharing his account of what it was like being perceived as a woman even as he carried certainty about his male identity with him through decades of music-making, marriage and parenting has taken on even greater importance, as Republicans justify their legislation by characterizing the desire to transition as the whim of confused people. Through a stirring memoir that comes out in June, TransElectric: My Life As a Cosmic Rock Star, and speaking engagements around it, Bullens is further fleshing out his lived testimony. “As I say in the book, I was putting a bomb in the middle of my life, but I couldn’t not do it,” he says of his decision to live openly as a transgender man. “Because it’s who I am. It’s who I’ve always been. I feel like I am in the right place in my life. And so that’s, I think, the power of my story — not just protesting on the street. There are other people who are much better at the political speech and the advocacy than I am. I have a story to tell.”

What Bullens is unsure of is whether he’ll stick around in Nashville, where he and his wife bought a house in 2020, to do that: “I mean, do you think I want to live there if I can’t perform there? If living in the state of Tennessee further restricts my being, why would I live there? And it’s not because I would be running away from the problem. It’s because it affects me as a human being. I’m not 21; I’m not 31; I’m not 41. I’m an elder now. Where am I going to live the rest of my life? Where am I going to be free to be who I am?”

He’s not the only one contemplating leaving Tennessee. Adeem the Artist has been measuring the kind of upbringing they want to give their young kid, whom they describe as having “a very elastic understanding of gender,” against tightening constraints in their home state. Already Adeem’s had a foretaste of a selective and subjective crackdown; last year, at a festival near Knoxville, they were hurried off stage mid-set, and later learned that they’d been accused of “talking about sexually explicit things in front of children,” on account of singing a dreamy, bashful song about kissing a guy, mentioning they/them pronouns and wearing a romper. They don’t want to also be denied future chances to provide their child with a different type of festival experience that they shared last year: watching a Dolly Parton impersonator together. “It was a really sweet and important moment I was grateful to give my kid,” they explain. “And the idea that somebody’s bigotry could restrict my freedom to take my kid to an event like that, to expose them to an artistic expression, is just bewildering.”

“It is a long-term issue for the state that will cause serious repercussions moving forward, because the rest of the world is going to continue to explore a deeper understanding of gender,” they go on. “The people of this state will grow up without that representation, without the language. My kid asks other kids what their pronouns are. It’s the same as asking someone what their name is. And the reality is, whether you like that or not, that’s the future. That is where we’re heading.”

Moving their family beyond the reach of the legislation won’t keep them from returning to The Volunteer State and wearing whatever feels right on stage. The only modifications they intend to make are to safeguard those who remain behind. “I will be at regional protests around Tennessee with drag queens and other performers as I’m available,” they promise. “If safety was my primary concern, I would not be an openly nonbinary, queer musician taking shots at Toby Keith within the country music world. I will collaborate with venues where possible to make shows 18 and up. I expect to make those concessions where necessary to embolden the businesses and the communities that need protection here.”

“We’re going to fight it with our art”

Houston Kendrick began interrogating the traditional models of masculinity he was surrounded with while growing up and growing into his musical inclinations in suburban Alabama. When he arrived to study and pursue music in Nashville — where sturdy, proven templates are frequently favored over conceptual daring and the smoothest path to professional success is set aside for straight, white, cis men bound for the country music machine — his devotion to refining his artistic identity as an expansive pop and R&B ruminator, unafraid to experiment, was inherently a bit transgressive. It helped that he could look elsewhere — to the elegance, interiority and queerness of Frank Ocean, and the vivid, virtuosic and liberatory fluidity of the Black and brown drag ballroom legends of New York City immortalized in the 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning.

“I think that being Black and gay, I always feel that there is something more to prove,” Kendrick reflects. “But I’ve really enjoyed the opportunity to create and grow and mature here, specifically because this is a pressure cooker for people like me. Access isn’t easily granted. You have to really believe in yourself and you have to believe in the art and the message that you want to convey. And I would not have been able to garner that kind of tenacity and endurance anywhere else. I really am grateful to Nashville. I’m grateful because I think that I have changed lots of minds, and I think I’m going to change a lot more minds.”

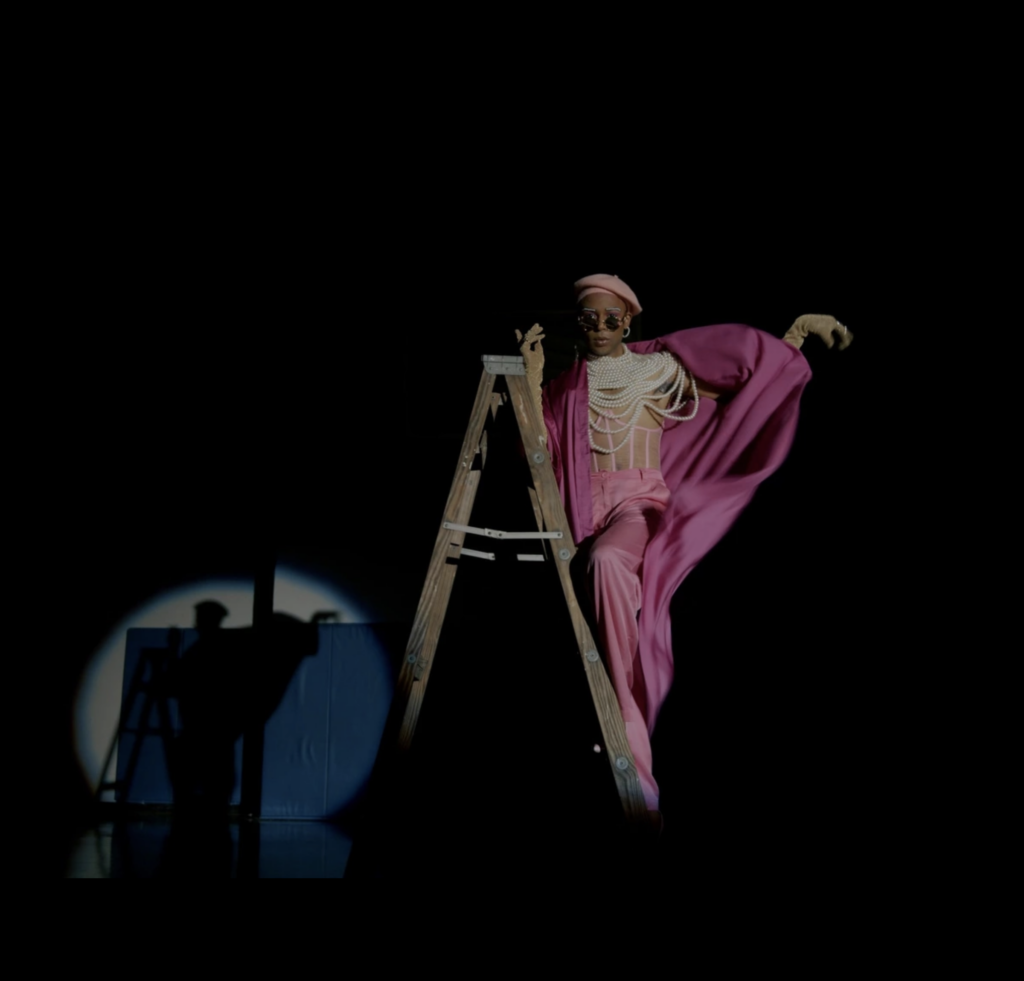

Courtesy of the artist

On his self-released 2021 album Small Infinity, stocked with airily arresting melodies and deft, moody shifts in tone of voice, Kendrick made room for owning and exploring his many sides, sketching his inner life, validating his youthful restlessness and teasing out unbounded desire. He also began working on a short film to accompany it. The video for his song “Concrete” has been in the works for two and a half years, and completed for at least one. Kendrick was impatient to release it, and his team’s search for label or distribution partners delayed the process. But he’s realized that, coming from a Nashville-repping visionary, its arrival later this week, on March 23, will register greater meaning; it depicts his inner life as a drag ball.

First he serves a masc look, “sort of like a little bit worker, overalls, Timbs, bandana, gold chains, just giving you real the Southern type.” Then he walks femme, “in this long, flowy, satin, caftan moment with pearls everywhere.” In the clip’s culminating scenes, he inhabits a third persona, dressed in purple and transcending both of the others. “So basically, the entire concept is how we coalesce the masculine and feminine without shame, because I think there’s room for both of those things in all of us,” he explains. “There is no binary, actually, at [the end]. There is just soaking up all that love in all this that is going on within me.”

Kendrick’s most lavish exploration of drag to date coincides with his resolve to grow even bolder in response to Tennessee’s new laws. “I guess I’m just gonna have to be a little bit louder,” he muses. “Is it crazy that I still have this sense of optimism? I feel like we’re in a renaissance of trans and queer creativity right now.”

“There’s this continued attempt to make people illegal, to make people feel unsafe, unworthy, undervalued and invisible. We’re going to fight it with our art, with our voices, with our bodies if we have to.”

Fixing it for the next generation

Ellen Angelico, a top-flight guitarist who’s been active on the Nashville circuit for just over a dozen years, realizes that the state’s Republican lawmakers probably have no concept of why the sort of advocacy Kendrick pledges is so vital. She says, “They don’t see the Nashville that I see.”

She recognized from the beginning of her Tennessee tenure that her queerness and, as she playfully puts it, “gender amorphous” presentation made seeking out solidarity and forging like-minded alliances just as essential as leaning into her nimble musicianship and deeply knowledgeable appreciation of country ancestors. The decor of her condo living room reflects that range: one wall holds vinyl LPs by Roger Miller, mid-20th century archetype of mischievously and masterfully witty songcraft; another displays posters from the girl-group tribute shows where she’s led bands assembled from the indie underground, the roots scene and teen rock camps alike; yet another commemorates one of the big concerts she’s played with the contemporary country star Cam. (Full disclosure: Angelico and I have taken a dive bar stage together as part of the backing band for a country drag show.)

Angelico’s strategizing quickly took on an organized form. She made a flow chart to guide conscientious decision-making about which side gigs to take. It prompts her to evaluate everything from the quality of the music and travel accommodations to the quality of an artist’s character (sample question: “Are they a known racist?”). Then there’s a spreadsheet she shares around town that lists dozens of top-tier pros she’s worked with who too often get passed over on the basis of their gender, gender variance, sexuality, race or age.

“I just want to connect people to the people they may not see,” she reasons. “The real solution to that problem lives a lot higher up the food chain than me. But I’ve got to do what I can.”

Over the years, Angelico’s grown far less willing to accommodate anyone’s expectation that she take on a femme appearance on stage. She scrolls through her phone in search of photographic evidence of a long-ago night when she let members of a band she was playing with pick out her look.

“You want to talk about banning drag?” she teases. “I’ll show you drag.”

In the old backstage photo on her screen, she’s unrecognizable.

“Like, this is just not a nice outfit: a crop top and tight jeans with the boots on the outside and lots of sparkles and big hair!”

Those days of dress up are long gone. Angelico pressed onward in her career, getting an instrumentalist of the year nod at the 2020 Americana Awards, as her musically accomplished, genuinely butch self. “I can just show up in a black T-shirt and jeans and fade into any band as long as I don’t open my mouth,” she says. “There are so many people like me that don’t have that choice, people who have the exact same skill set that I do, but are Black or they are more visibly trans than I am.”

She’s spent the last few weeks conferring with a member of the Metro Human Relations Commission who’s transgender and firing off emails to state representatives, but her highest priority right now is encouraging the artistic leanings of the city’s LGBTQIA+ youth. “The only way that I know to fix it for the next generation is just to continue showing up and being myself,” she says, while packing a lunch to take to her job at an East Nashville music store. “I’m going to Fanny’s [House of Music] here in a couple of minutes, and there’s going to be a kid that comes in and sees me in the fullness of myself in that store and maybe feels like, ‘OK, there’s an adult who looks like me, who feels that they have permission to be creative. So I have permission to be creative.’ “

Finding people further down the road to self-acceptance was what really turned things around for Eureka O’Hara as she stood on the cusp of adulthood in her Johnson City hometown. She lost friends and endured bullying and banishment from church before being embraced by the local drag community. Veteran performer Jacqueline St. James became her drag mother. “It created a family for me, and a place to belong in East Tennessee,” recalls O’Hara. “Everywhere else I went, I did not feel safe and I had to hide a lot of who I was. But not there; not in drag.”

Her professional opportunities multiplied after her memorable runs on seasons 9 and 10 of RuPaul’s Drag Race and season 6 of RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars. But none excited her more than the prospect of joining two other queens, Shangela and Bob the Drag Queen, on another series, We’re Here. Each episode begins with a self-aware conceit where the three arrive like glamorous aliens landing in potentially hostile landscapes (i.e. culturally conservative towns). From there, they proceed to meet the locals, make LQGBTIA+ folks in their midst feel seen, heard and less alone and stage zealously uplifting drag shows for everyone. Says O’Hara, “I wanted a job where I could give back to communities like mine that need it.”

It’s not lost on her that this showcase of drag’s therapeutic and communal sides is the absolute opposite of the picture Tennessee Republicans are painting: “I wish that some of those people would just watch an episode of We’re Here, you know, watch RuPaul’s Drag Race, watch anything that humanizes queer people, so they can realize that we’re just like them.”

O’Hara’s career has taken her far from the South, but she feels it’s more important than ever to return to her home club in Johnson City, New Beginnings, and be there “with bells on, looking fabulous, to show them my appreciation for keeping me alive.”