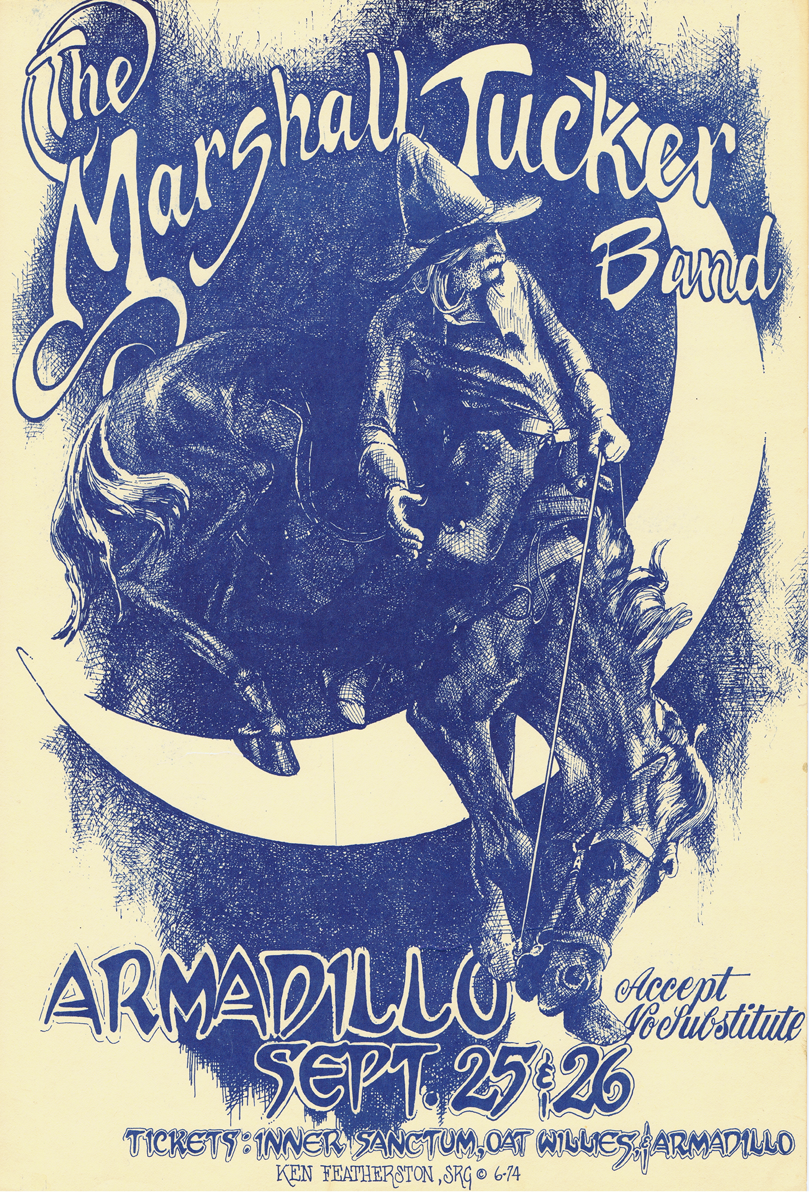

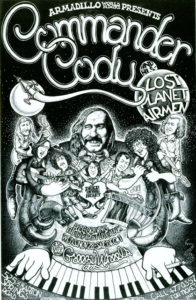

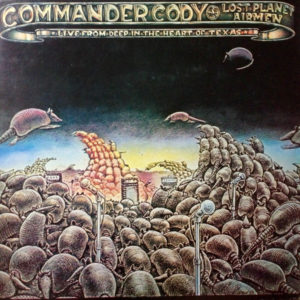

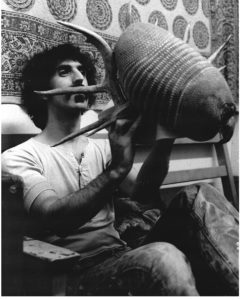

All images provided by Austin Museum of Popular Culture.

Stories from the front lines of the fabled Armadillo World Headquarters

By Jeff McCord

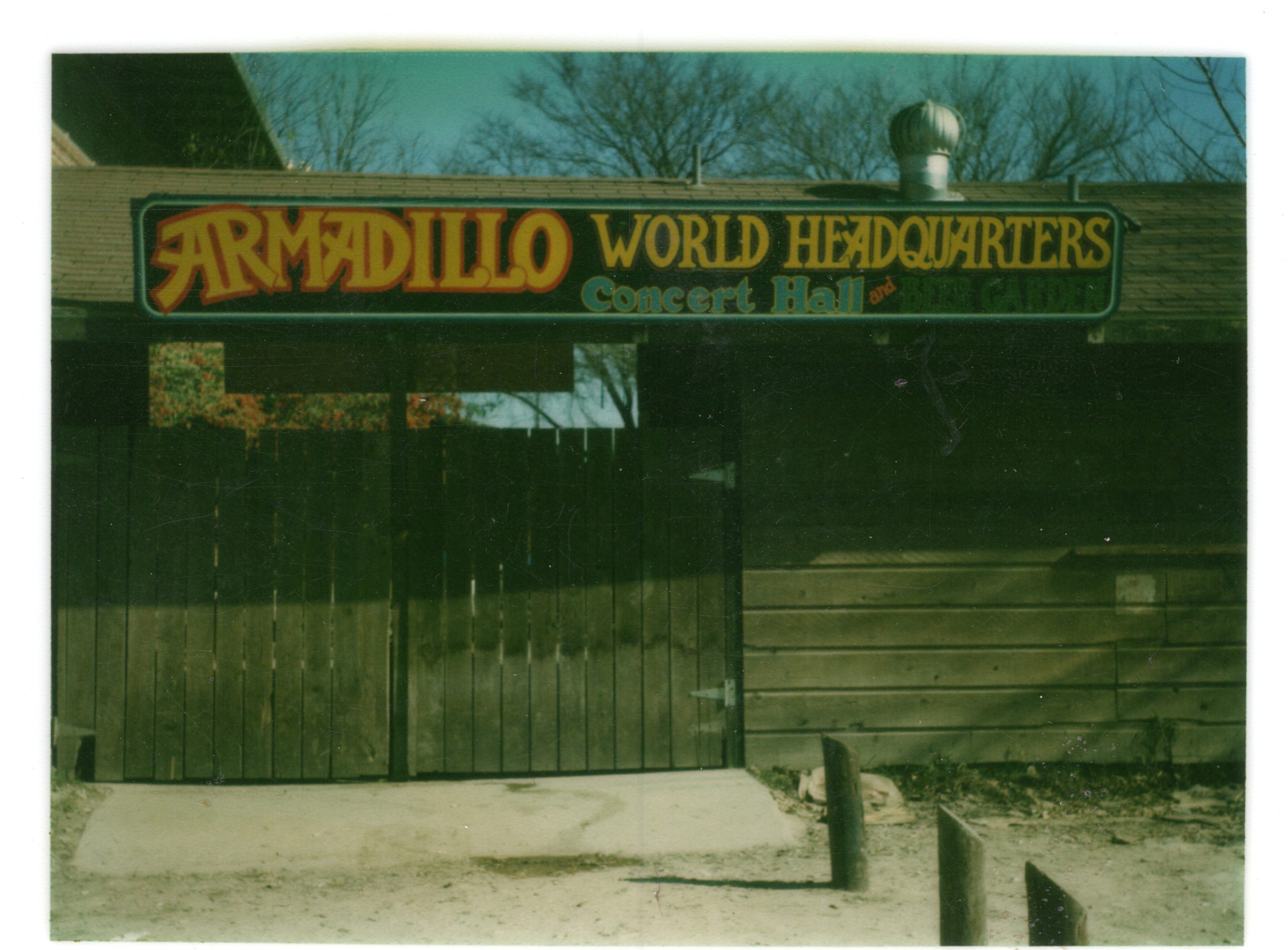

We’ve been commemorating the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Armadillo World Headquarters all this month at KUTX, with many features and a radio documentary, Back Home to the Armadillo. Pre-COVID, a large concert was also planned for the festivities.

And despite laying out a case for the venue, many of you are no doubt wondering – why? What is the big deal about a club with a silly name that closed forty years ago? Lots of great music venues have come and gone. The pandemic is taking them from us right now. So what is it that made this funky, un-air-conditioned warehouse so memorable?

Happenstance, as much as anything. The Armadillo arrived at a pivotal point in time in this sleepy college town. The counter-culture was on the rise, clashing with a redneck vibe that had permeated the city. The Armadillo didn’t create the cosmic cowboy movement or any of the varied musical branches that grew from it, but it became its defacto clubhouse, a place to hang, drink beer, smoke pot, stop, and look firsthand at what was going down.

No one person made this happen. The Dillo was a collective, held together by the barest of threads. Eddie Wilson found the abandoned hulking shell, as detailed in his memoir, and while he oversaw the opening and the venue’s early era, he had a lot of help. Bobby Hedderman did most of the booking, Mike Tolleson was their attorney, and Hank Alrich would rescue the place from bankruptcy and oversee their final years. Surrounding them was a cast of characters as rich as any Dickens novel. They kept the place going, doing everything that needed to be done.

What follows are stories, remembrances and eyewitness accounts, taken from new interviews and from the Armadillo History Project ten years ago.

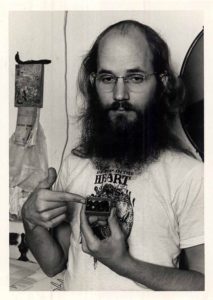

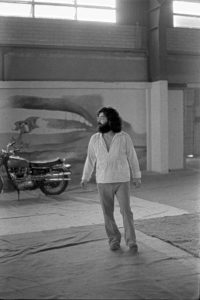

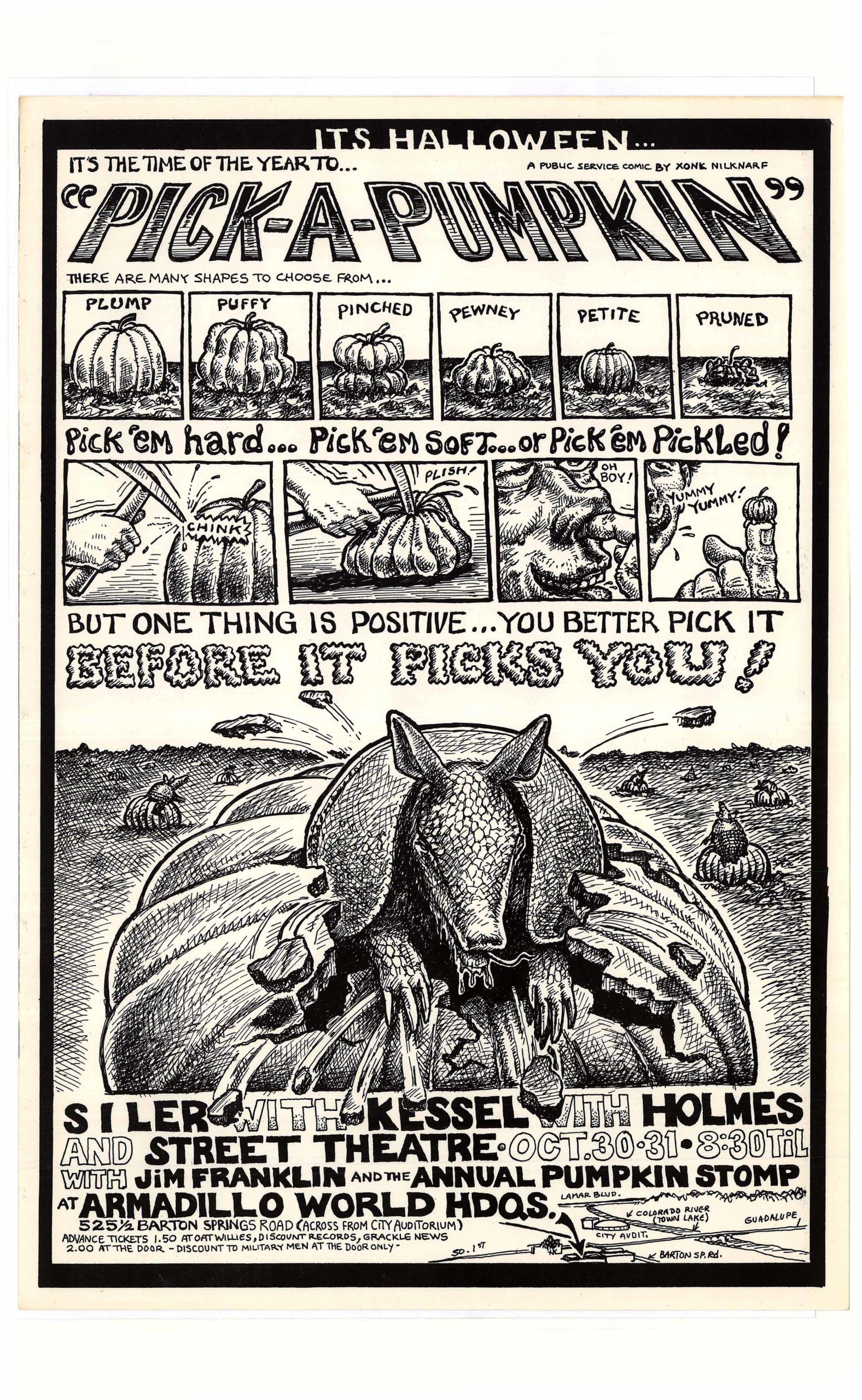

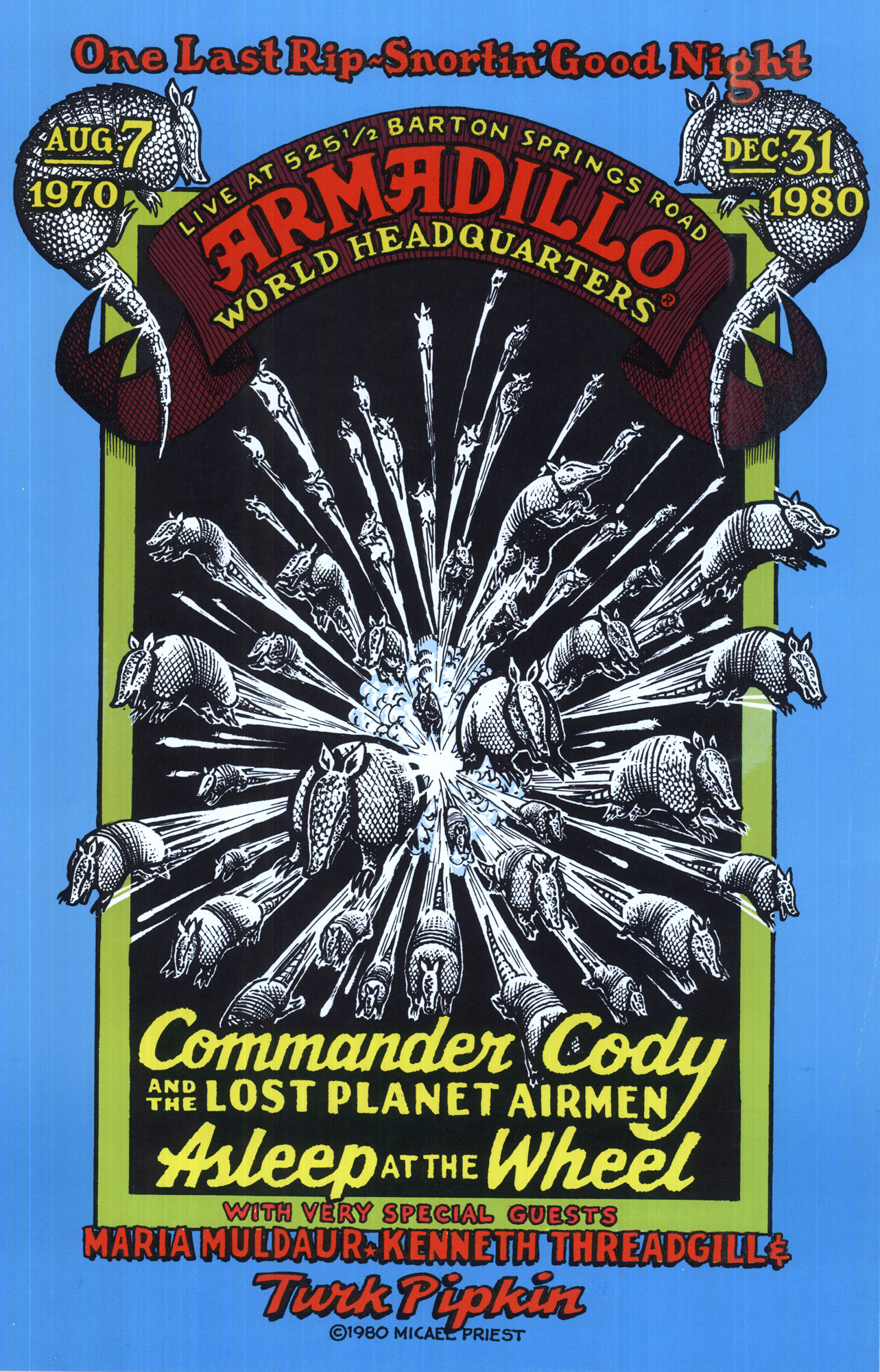

Everyone has a slightly different interpretation of the history of the Armadillo, the huge 1500 capacity building which opened in August of 1970 and closed a little more than a decade later, on New Year’s Eve, 1980. But everyone agrees on their spiritual leader, Jim Franklin. Franklin, whose original Armadillo poster inspired the venue’s namesake, is a serious artist whose discomfort with using his art for commercial purposes balanced his zeal for being their crazed emcee, decked out in his full armadillo regalia.

“I had found a handbook on the mammals of North America. And there was a painting of an armadillo. Franklin recalls. “It keyed a memory of a hunting trip with my father, where we were creeping up on a sound in the bush. And it was an armadillo. My father laughed. I slipped under the wire and when it stood up. I froze. It goes back to digging. I get right up to it. The damn thing turned around and walked between my legs.”

“I get a request to do a handbill for a love in concert at Woolridge Park. The armadillo was occupying my imagination for a couple of days. I did an ink drawing. It’s just come across a pack of papers and about three or four joints rolled and laying there on the ground, and the armadillo’s got one in its mouth puffing. And overnight it turned the armadillo on to all the hipsters. What struck me was that at the time beatniks were getting beaten up by bubbas from the university, frats in Austin. It was dangerous if you had long hair to walk around the streets of Austin at night.”

“So the idea of using the armadillo as to illustrate the beatnik audience, I thought, well, perfect, because we’re always getting run over by rednecks and pickups.”

Franklin had been involved in the Vulcan Gas Company, an earlier attempt at a counter-culture venue downtown on South Congress, which hosted the Thirteenth Floor Elevators and the Velvet Underground, among others.

“I had been going to the Vulcan,” recalls writer Bill Bentley, “which was a great club. But, you know, it was unsustainable because the people that ran it just really didn’t know what they were doing. They didn’t have a beer license. So there was never any money to be made there.”

In his memoir, Eddie Wilson recalls visiting the Vulcan in the daytime in a suit and tie, trying to warn them of an impending raid. No one would speak to him. When Wilson acquired the Armadillo building, the Vulcan had been closed for some time. Franklin was one of the first to approach him.

In his memoir, Eddie Wilson recalls visiting the Vulcan in the daytime in a suit and tie, trying to warn them of an impending raid. No one would speak to him. When Wilson acquired the Armadillo building, the Vulcan had been closed for some time. Franklin was one of the first to approach him.

“Franklin came to me and said, you really need some help, And this is Bobby Hedderman. He’ll probably be able to help you.” Wilson explains. “We started recruiting people who heard about us from Houston, Dallas, Oklahoma. And they would try to get to Austin because they heard there was a little stronghold of tolerance for the same things they were getting whipped with rubber hoses for in Dallas.”

“ I had to create my own universe. I got [to Austin] in ’48. I was five years old. Mama had a nursery. Everything I’ve ever done has been an industrial version, kind of a nuclear version of what my mother did with her nursery school.”

Wilson recalls meeting Mike Tolleson. “Tolleson walked in while we were trying to get scrubbed up for the opening. We had the place maybe two, three weeks. We didn’t have time. We didn’t have money to do anything. So the only reasonable thing to do was, you know, charge a dollar and open the doors and see if we could start bringing some money in. When Tolleson heard me talking about what I obviously didn’t know anything about, he knew I was a receptacle for a lot of information. And he asked me if he could be a part of it. And I said, sure, I’ve got an extra bedroom and the house. I don’t have any money to pay for salaries or anything. And we suddenly had an entertainment lawyer.”

“When I walk into the building the first time,” says Tolleson, ”there was Eddie, and Jim [Franklin] had moved into space in the back and set up a studio. They were painting and cleaning up. I knew who Jim was. And I learned that Spencer Perskin of Shiva’s Headband was part of the organization, which was good because they were the only band in town that had a record deal. I mean, from the moment I got here, I could be doing this 24 hours a day. That’s the way it was from the beginning. There is no end of things to be done. So it was get up and go down there and do it, go back home to sleep, and get up and go do it again. The Armadillo for like five years is like having a party in your living room every night.”

Eddie Wilson:

“Well, it was a picture, the Hole in the Wall Gang, a place as big as a canyon in the middle of town, hidden completely from sight behind the Skating Palace.”

“You still had to keep asking to find it. Once you walked through that moonscape parking lot and then into that beer garden, you were suddenly on the set of a whole new movie. We called it the Beer Garden of Eden. It was a world in itself completely devoid of outside influences. And so people came. in and enjoyed stretching the limits of their own imaginations.”

Within the first week, Tolleson remembers, “we had no money. I mean, whatever money there was, got it open. And then after that, it was like a week to week to week to week to just make just to pay the rent, keep the lights on.”

“Eddie and Bobby and I would get up and go down to the Armadillo and spend all day trying to figure out how to put enough people in the place to pay the bills. The vision, I think, was always that we’re gonna make it. It’s going to get better. I think the first name that we had, other than local talent that would draw, was Freddie King. Another big act we had was The Incredible String Band. And we bet real wrong on John Sebastian. losing five thousand dollars, one of the biggest hits that I can remember taking. Nobody showed up. In those days when we opened the place, it had no connections to the outside world. One of the first things that I’m doing is getting on the phone with a major talent agents saying, hey, we’ve got a venue here, we’re looking for talent. That took a lot of effort just to get them to recognize us as being a viable facility in Austin, Texas, during those days when bands didn’t want to come to a redneck area.”

Austin writer and musician Jesse Sublett, who lead the Skunks and co-wrote Wilson’s memoir, discovered the Armadillo’s instant appeal. “I think for anybody who’s not a baby boomer, it’s really hard to really put your mind there because, anywhere else in Texas, the long hairs were getting beat up you just you didn’t belong anywhere. Here’s a place with things that you related to, and people that you related to, but it was big enough that the cops weren’t going to come in there and bust you for smoking a joint.”

“I came to the Armadillo in 1971,” recalls writer Joe Nick Patoski.” I was a radio deejay up in Arlington, and I wanted to see why the bands, in particular Captain Beefheart and the Flying Burrito Brothers, shit that we were playing on the radio, how come these acts weren’t coming to Dallas or to Houston, but they’re passing through Austin. What was this place? So I drove down one Saturday morning and walk in about 10 am. I woke up Jim Franklin, hung out with him a little while. It took a little bit, it was confusing having to figure out the pecking order. Eddie seemed to be in charge more than the others did, and talking to him I tried to actually find out what their schedule was because I wanted to announce it on the radio. But I was more organized than they were.”

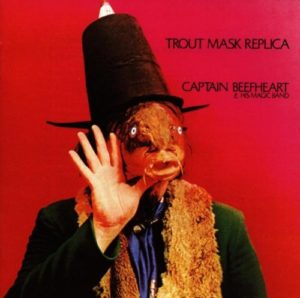

Bill Bentley was at Captain Beefheart’s first Armadillo show. “Ry Cooder and Captain Beefheart played in 1971, when the stage was still in the back of the venue. Ry was good. But, you know, being in Texas, we had a ton of great guitar players, so I was impressed by Ry but he didn’t knock my head off. Franklin came out on roller skates with his armadillo head on and introduced Beefheart, and then the Beefheart band came out, the original Magic Band, and just started blowing out.”

In a 2010 interview, artist Micael Priest (who died in 2018) recalled being there, too. “ I have a boy who was born the year that Armadillo opened. In fact, when he was nine weeks old, he and I went to see Captain Beefheart for the first time. It was after Trout Mask Replica come out. And it was just the most astounding thing I had ever seen in my whole life.”

“Beefheart had a soprano sax and stuck the microphone up in the soprano so that just there was cacophony,” says Bentley “A lot of people started leaving because they had not they did not know what Beefheart was about. This wasn’t “Diddy-Wah Diddy”, it was just out of control. A lot of people left. I remember telling my friend that night ‘You know what to do here, man. When Beefheart plays, let people in free and then charge them to leave.”

Alongside Beefheart and Freddie King, many other acts graced the Armadillo’s stage in their first year – Lightnin’ Hopkins, Mance Lipscomb, the Flying Burrito Brothers, even Ravi Shankar.

Rikke House, the famed Armadillo kitchen maven dubbed the Guacamole Queen by Jim Franklin, recalled the Shankar show in an interview a year before her death in 2011. “Oh yeah, Ravi Shankar. We thought, cool -macrobiotic food. Brown rice curry, organic tea. Instead, it was, ‘I like Lipton’s tea. I don’t eat curry.’ We ended up feeding him white rice.”

“He was not interested in health food,” concurs Wilson. “He wanted Kentucky Fried Chicken.”

For most though, the Armadillo kitchen offered a welcome respite from the usual road food, and actually helped pull in acts. House helped put the kitchen together. “We have hardly any money. So I went to San Antonio to these derelict places where they had stoves for a hundred dollars and we’d bring them up. All of the girls would take their bras off in the kitchen, wear real tight t-shirts and the guys would come up and repair everything. So we actually furnished everything for the kitchen real cheap and just it just kept going.”

House explained that the Beer Garden had similar origins. “The UT shuttle bus drivers went on strike. By then I was doing lunch specials or dinner specials and we had beer. Barely opened, but there was nothing out there, just tables and chairs in the hot sun. And they said, if you will feed us and give us a pitcher beer, each a day will come. And they came and built it. All the wood and trellises and plants. It was beautiful.”

Bentley laughs at the memory.

“When the Flatlanders [Joe Ely, Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Buth Hancock] started playing in the Beer Garden, it got crazy ’cause people would get so drunk out there.”

“If I remember right, it was free. And the beer was like a buck a pitcher or even cheaper. So people would just, you know, I bet you anything the staff would come the next day and there’d be people sleeping it off.”

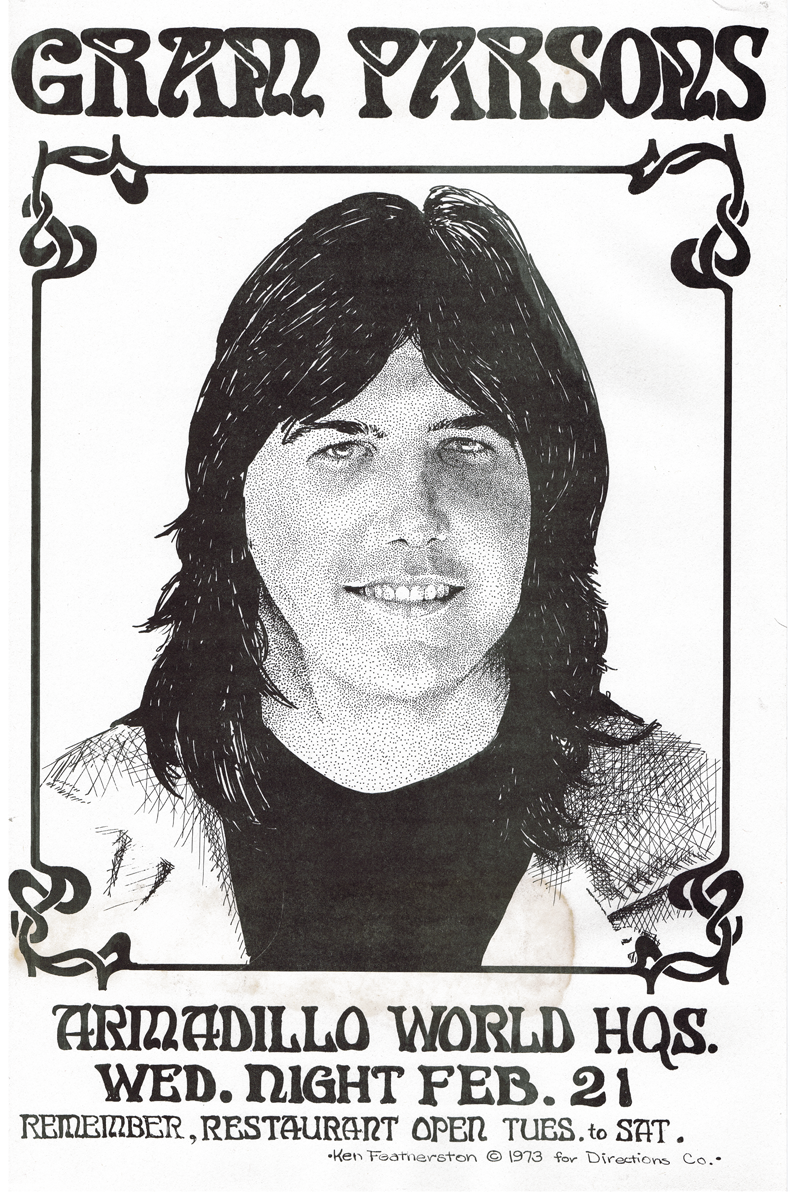

“The hippies at the Armadillo learned by experience.,” explains Patoski. “When Bill Ham four-walled [rented] the venue for a ZZ Top show, they saw how it made money. These people, even if they weren’t real pros, loved treating their entertainers with hippie love, feeding them, and doing all this stuff because they couldn’t provide other things. Never mind they didn’t have air conditioning. It was a kindness built on naiveite and an inability to come up with much capital. So, you know, Gram Parsons was crazy to score some weed and the Armadillo got him weed. And, for touring bands, it’s like, shrimp enchiladas.”

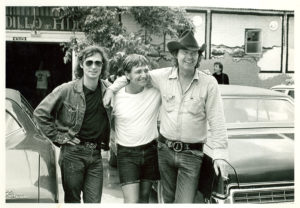

With the Armadillo gaining notoriety, it wasn’t long before a new arrival to Austin, Willie Nelson, would show up there. Wilson recalls meeting him at the bar and inviting him to play. Nelson’s triumphant return to Texas was marked on the Armadillo stage in July of 1972.

Rikke House recalls the show. According to her, Nelson was scared to play there. “And we were scared to have him play there because that was early 70s when the rednecks beat up hippies It was beautiful, though, because of the music. Everyone enjoyed it, no animosity at all. By the end of the night, he’s just grinnin’.”

This was a milestone in the Outlaw Country movement, but it wouldn’t last. The Nelson-Armadillo connection would unravel after a couple of more shows, “When you think about all that period of Willie and Waylon and then Tom T. Hall, it was short-lived. Willie settles on the Texas Opry House, which has air conditioning, sells drinks.” remembers Patoski. “Bobby Hedderman in the early years was really responsible for doing booking. Hedderman was also responsible for alienating Willie’s people forever.”

Eddie Wilsons remembers it differently. “We had an aversion to guns that some of his [Willie’s] cohorts couldn’t abide by. And so he ended up with his own place on the other side of Congress.”

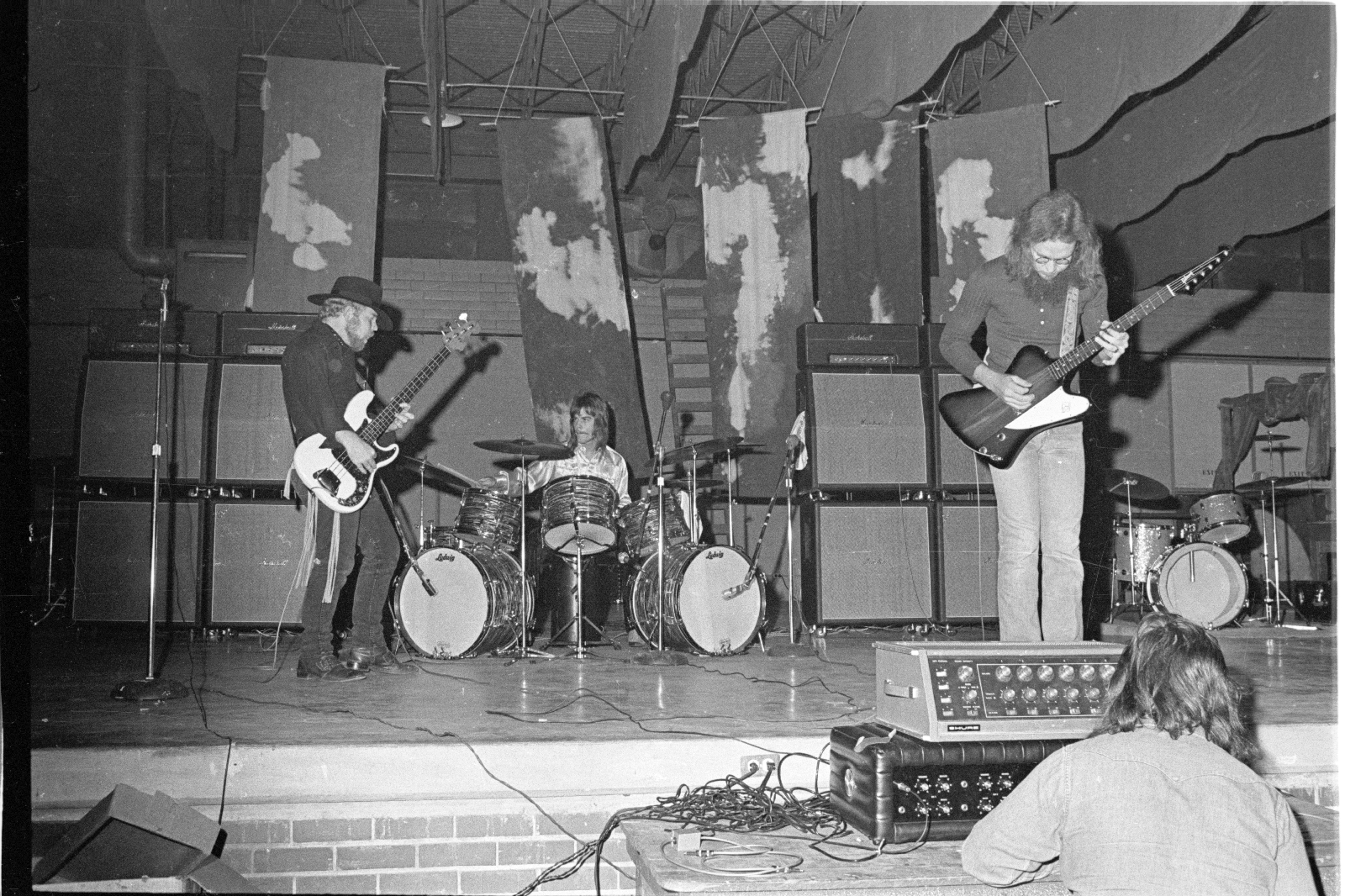

In 1972, though, Nelson was inviting his friends down to the Armadillo. Waylon Jennings played with Willie on December 1st. On the next night, the opening band was a Bay Area band that began in Ann Arbor, and they would become one of the Armadillo’s unlikely mainstays – Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen.

Their guitarist, Bill Kirchen, who calls Austin home these days, talks about that night. “I don’t think we’d met Waylon before. I’d been singing “Only Daddy That’ll Walk the Line” since the 60s. I was a big fan. I mean, who wouldn’t be? I think a lot of people were there to see us, though. Waylon had not quite blown up like he would, you know, in a year or so later. He was huge, but he was still transitioning from the hard country to the alternative. And we were firmly in the alternative already. I remember him sitting on a chair there on stage, right offstage. We all come together at one point he just stood up and went, ‘I was talking to some friends and they said you weren’t country. And I said you were.’ And then he sat back down. I’m like, ‘Okay. My work here is done.”

“Another thing I remember was they invited us up to their hotel room after the show because they were playing poker. And we said, yeah, we’ll go to the game because we’d been playing poker on the bus. Of course, we played nickel-dime. We get to the room. Ralph Mooney is asleep on one of the two beds. Everybody else is sitting around on the other bed. There’s a big ass pile of money in the bed, and they explain the rules to us ‘This is a called pot-limit poker. In other words, there’s four hundred dollars in the pot. That’s all you can bet on that round.’ We’re like, ‘I think our mothers are calling us.’ We basically slink out of the room.”

Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen would become one of the Armadillo’s most successful acts, selling out and playing there more frequently than any other touring act, up until the band imploded in 1976. In late 1973, they would record a live album at the Dillo, Deep in the Heart of Texas, complete with cover illustration by Jim Franklin.

“We instantly fell in love with the whole shebang of the Armadillo.”

“We considered ourselves the out-of-town house band. We were treated just like royalty when we got there. One of the last times we landed at that old airport, they had their limos waiting on the tarmac, and a bunch of the Armadillo waitresses came out and were doing the can-can.”

Cody would soon bring along another Bay Area-based band to the Dillo, Asleep at the Wheel, and Ray Benson describes their instant love affair.

“You look out at the audience and they were you. The Armadillo was a very friendly place, probably a place you might be able to find a little marijuana if you turned to the right or left or right, other psychedelic drugs, and an incredibly diverse array of music. We parked our bus in the parking lot and lived on the bus. There was a kitchen, there was beer. They would feed you. They made these nachos, Rikke, the Guacamole Queen. Rikke was the ship.”

Frank Zappa would soon start a residency of sorts at the Dillo, too, falling in love with the atmosphere, dancing with the Guacamole Queen onstage (and later immortalizing her in song). Like Cody, Zappa would record his own live album there in 1975.

And there was Bruce Springsteen’s dramatic Armadillo debut in 1974, detailed here. “One of the most exciting shows I ever saw,” says Bentley. “And I’m not the big Bruce head like most people are. But I totally respect him. The first night there are probably about 300 people, respectable. The second night you couldn’t sneak in. They knew what they were doing. Because Austin had that great sort of musical grapevine. That band was just completely out of their minds great. They still had that crazy drummer, Mad Dog Lopez, who I loved. And those songs on Wild, Innocent. It was incredible.”

Just a few years into its existence, The Armadillo was making big impressions and getting written up in the national press.

“I moved here right away.” – Ray Benson, following Asleep at the Wheel’s first Armadillo gig.

He wasn’t the only one. We began our month of coverage with this piece describing how the Dillo led me here from San Antonio. Many others told me the same thing.

The Armadillo brought KUTX’s Jody Denberg here. “I was living in El Paso, Texas, and I was a big prog rock fan. I traveled to Austin to go see Genesis and the Armadillo booked this other prog-rock band the next day, Nektar. So I went to the Armadillo for the first time in 1976. Having grown up in New York and only seen concerts in big arenas and coming into this place, the intimacy of it, I couldn’t believe you could just walk in and get that close to a band. I thought, I want to move to Austin and I want to go to the Armadillo World Headquarters all the time. And I did.”

“I saw Van Morrison at the Armadillo. I think it was seventy-eight and seventy-nine. I know I saw Frank Zappa as soon as I could. I just went there all the time. It was that eclectic booking approach that appealed to the eclectic music lover in me and really symbolized what I found in the rest of Austin as well.”

Bentley was an early convert. “I’d been going to school up in Georgetown and I came down to Austin to take a couple of classes and I had a little night job down there for the summer. So August 1970 was gonna be like, back to Georgetown. And I went to the Armadillo opening night and I swear, after an hour I went like, screw Georgetown. I’m not going back to Georgetown. This is too cool.”

Few, if any other music venues held this kind of sway. The Armadillo became an indispensable part of the city’s fabric almost as soon as it opened.

And their kitchen-sink booking policy served them well until the end. You never knew what you were going to see there.

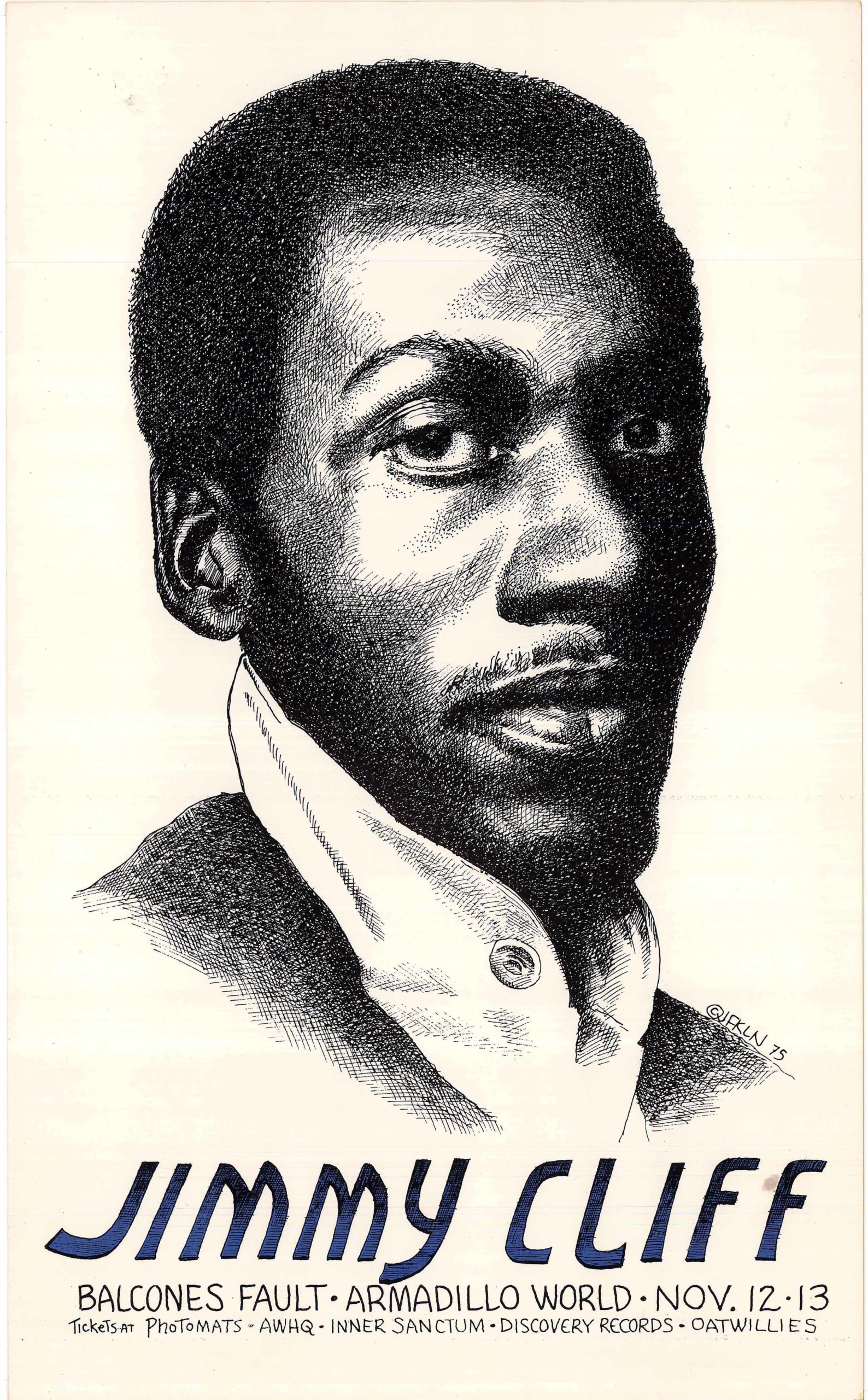

KUT/KUTX host John Hanson recalls great shows by Freddie King, Funkadelic, Ray Charles and Jimmy Cliff.

“The Armadillo was basically a white venue. When they started bringing in African-American acts and reggae acts, that’s what I actually started checking it out. Those audiences were maybe 75 percent white and maybe 25 or 30 percent African-American. I didn’t see any racial strife, people minded their own business, they were there to have a good time, drink a whole lot of beer and whatever. The venue reflected laid-back Austin at the time.“

“They didn’t have a lot of Black music,” remembers Bentley. “I know two of the best shows I ever saw there, though, were Jimmy Cliff and Toots and the Maytals, but they really didn’t have much soul. By the time Antone’s opened in 74, they started getting acts like Bobby Bland. For whatever reason, it wasn’t a soul joint. It would have been great if, like, Curtis Mayfield had come or somebody like that.”

“Hippies, people that are different offbeat. It was the cultural center, not just for Austin, but Texas in the 1970s,” recalls Patoski. “There are all these you know what I consider satellites in the forms of great music clubs, but there was a certain critical mass when you went to go see road bands and that was all the Armadillo. It was a local hang for the beer garden. It was always a good place to listen to bands outside, but mainly to drink beer and hang out with your friends.”

It was a cultural center for the employees holding the place together, too, and not without its share of drama.

Rikke House tells how she would run out of pot. “I’d go into the audience and follow the smells. I’d go, ‘Hey, the narcs are here.’ and they’d hand over their pot. I did it quite often.”

And she tells the story of the time no one scheduled showed up to help her cook 100 turkeys for a Thanksgiving benefit. Or when she first discovered Jim Franklin’s warning mural outside the men’s room, threatening to turn guys caught beating off over the Guacamole Queen.

“There was a shower for the employees that was there. So one day I stepped out, was drying off.

And I looked up and saw it [the mural]. I’d had no idea. I ran upstairs to Jim’s room naked. I was pissed.

“He opens the door, says “I wondered how long it would take you.” He throws a blanket at me to wrap up and he says, ‘This is so-and-so. He’s here for a New York Times magazine interview.’”

And there’s this story, from a time when the Armadillo was having a problem with overzealous security, told by longtime employee Bruce Willenzik.

“I shouldn’t have been working there that night. But we were trying to keep security under control and a situation happened. It was the Black Oak show, November of 77. And the fire marshal had given us a bunch of hell about people putting chairs in fire aisles. I’ve been back in the security office, had just burned a big one, and was headed back to the kitchen. And I see this big redneck put two chairs down in the fire aisle. He’s got this girl with him with glasses on and curly hair. He’s big. So I go over there to go talk to him. The first band had just started in. They’ve never played there before. Way too loud. The guy could not hear me at all. I’m trying to tell him he’s got to move. ‘You gotta move!’ He can’t hear me. He didn’t know who the hell I was. I’m probably not handling it well and I’m feeling the pressure of the fire marshal who said, we’re gonna ticket you. We’re gonna close you down. So I was fairly aggressive with the guy. He could not hear me at all. Finally, he stood up. I thought he’d heard me. So I grabbed his chair. She stood up. I grabbed hers. He took exception and took a swing at me.”

“I saw the swing coming straight in. He was much bigger than me. It’s only time a customer ever hit me.”

“By then the first song is over. ‘No, you don’t understand,’ I say. ‘I’m trying to help you.’ ‘What? What Do you mean you’re trying to help me?’ ‘You’re in the wrong place.’ And right as I said that, I saw a big arm, Jerry’s arm, go across the guy’s neck and I look and there’s terrible Tom cocking his fist to go right through the guy’s jaw. And I’m thinking, got to stop the brutality. I don’t know this guy, and he just punched me. But I’m not gonna let him get hurt. ‘STOP!’ I scream and I can be a human megaphone when I need to. They both froze. ‘He’s a friend from high school. Leave him alone.’ ‘Sorry, man.’ They back off. And the guy is totally freaked. So is his girl.”

“So I explain to him, now that the band’s down enough, he can hear me. ‘I’m going to move you to a better place where you’re legal.’ ‘Oh, man. I’m sorry. I thought you were trying to steal my chair.’ Don’t worry about it, it’s all OK.’ ‘No, I’m sorry, man. I’m sorry.’ All these apologies I get people to scooch over. We get the chairs in there, we get them set. They’re still apologizing. And I said to the guy, ‘Look, you’re OK. Security is not going to touch you because they know you’re a friend of mine now. And I’m not a lawyer. I’m not going to sue you.’

“And she goes, ‘Oooooh!’ Oh, shit. I said the wrong thing. What did I say? She said, ‘We’re both lawyers.’ You got to be kidding me, I think. What kind of lawyer hits a stranger? She says. “My husband Bill is Attorney General of Arkansas, and my name’s Hillary. I work for the Rose Law Firm in Little Rock.’ “

“’Oh, my God. Sorry.’ ’No, you don’t need to apologize. We need to apologize.’ So I go back to the kitchen and tell my little brother what just happened. And I said, ‘Man, we’ve got to get serious about the brutality here, because imagine the headline, ‘Attorney General of Arkansas gets Mauled at the Armadillo’. We’d have been out of business. During the break, I went brought him beer and nachos and I was all apologetic and they were all apologetic, it was really funny. So at the end of the gig, I went and gave them the whole tour, and left them with the band.”

“Twenty-two years later, I’m at the opening of the new airport, here’s Bill Clinton again. He was the chair of the new airport terminal task force. I was on the board. I was with all the VIPs and he comes right up to me. I said, ‘I met you at 77, at the Armadillo, the Black Oak show.’ ‘You know, Hillary and I were talking about that last night. What a great experience that was, our best night ever in Austin. Somebody on the staff was so nice to us. That was you, wasn’t it?’ He comes right through the thing. He’s all hugging me. He’s all friendly. He comes back four times to thank me. Mayor Watson, on the bus on the way back, asks ‘What’s the deal with you and Clinton?’ ‘Old times,’ I say.”

By 1977, Eddie Wilson had moved on and the Armadillo had gone through a painful bankruptcy and reorganization.

“I think it was a local radio station that blew the whistle on us, you know, we’re going to sue if you don’t pay.” Tolleson recalls. “And that led to an internal restructuring, a bankruptcy, Chapter 11. Hank Alrich, who had loaned us a fairly large sum of money, he took over. He had been part of our group and musician and an engineer and built out a studio in the back. It was a natural evolution. By then, the systems were in place. So we were able to scale down, scale back the staff, and continue going.”

Alrich would stir a new genre into the Armadillo cake — jazz. Over fifty prominent jazz acts would appear in the Dillo’s final years, including giants like Sonny Rollins and Charles Mingus.

Dr. James Polk remembers performing there. “I had a band called James Polk and Company. They became Passenger later on, kicked me out when I went on the road with Ray Charles. The beatnik era, you know, you sat on the floor. And I met a lot of people there. Herbie Hancock, Eddie Harris. It was very nice while it lasted. I wish we’d had something like that again. If we could get rid of this coronavirus.”

Future KUTX host Jay Trachtenberg rolled into town around this time. “I was a grad student. I didn’t have a lot of discretionary funds, but I saw the Heath Brothers who were sensational. I saw Old and New Dreams. I remember at the Heath Brothers, there couldn’t have been more than 50 people in the house.”

“The way they gambled early on, they tried to run it like a Fillmore concert hall,” says Patoski. “ John Sebastian almost caused the place to close because they bet so hard on him. Money for an act like that was so big as opposed to a Old and New Dreams, which, you know, you learn to take a risk and you’re going to lose a little bit on this one. But they did that on the country end, and kind of on the roots bluegrass end they did it with country-rock, anything vaguely country.”

“I mean, you look at it — Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris and Linda Ronstadt playing with Little Feat and Bruce Springsteen for a dollar — seeing Alvin Crow scare the shit out of him before he went on the stage. That was great. Who could have predicted that?”

“There were some bad acts and, you know, cover bands and even some of the house bands weren’t my cup of tea. The local bands were less impressive to Armadillo than they were in other clubs. And I remember the air conditioning experiment when they tried to blow refrigerated air with big blowers into the club being such a joke. The carpets reeked of fermented beer and puke combined. But from the outside looking in by the time they emerge after bankruptcy, the Armadillo is an institution. Everybody wants to play there, even though it may be a dump. Why would anyone want to play CBGB’s or the Rat in Boston? I mean, these are toilets. It’s the rep. At the Armadillo, the bands were treated well. It gets beyond the money. By 1976, Austin was a music town. It wasn’t just, you know, cosmic cowboys anymore, but there were all these musical tribes and through Inner Sanctum, the record shop, and until the end of KOKE-FM in 1977, you had these arms. So it was like, service these music tribes.”

Punk and new wave were exploding on the scene, and the Dillo took note. The Police and Elvis Costello made their Austin debuts. Austin author Cindy Marabito recalls the Armadillo debut of the Dicks, one of the city’s seminal punk bands.

“You can blame the Armadillo for bringing hardcore to Austin. God bless the Armadillo.”

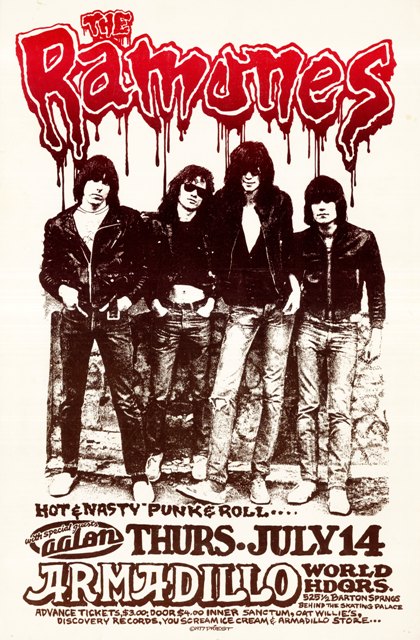

Micael Priest had lots of tales of this era, such as trying to dissuade a sickly-looking Joey Ramone from wearing his leather jacket during the heat of their summer ’77 debut. “I never had so much fun in 50 minutes. And when they were done, [Joey] just fell over. I went to pick him up and he didn’t weigh anything. It was like picking up a broken kite or a real old kitty.”

Or the time he was imitating David Byrne’s spasmodic moves backstage after the Talking Heads played, rolling his eyes up into his head, only to open them and see… David Byrne. “Yeah, just like that,” Byrne replied.

Priest also claims to have contributed to the band’s future repertoire. At a backstage party after the Head’s 1980 big band show, someone asked Micael how he was doing. “And I said, ‘High, high, high, high, high’. The next thing we know, it’s on a record.”

Larry Seaman was in Standing Waves, already making a name for themselves in the exploding scene at Rauls. He recalls opening the Austin debut of the Pretenders. “We played really well, people are cheering wildly. And it’s like, man, an encore. We get on the stairs to get up on the stage and the Pretenders rather large stage manager is there, dissuading us from continuing. So, our manager Roland [Swenson, soon to be co-founder and managing director of SXSW], comes running up saying, “What are you doing? Go, go!” and shoves us past the guy. We play the encore, and in turn, the guy shoves Roland down the stairs. The glory of rock and roll.”

Bill Bentley recalls the Clash/Joe Ely show as a pinnacle. “Ely was sort of like Texas punk anyway, the velocity that he played at was always really high. He played the most amazing — I’d never seen Joe play a set like that. And the Clash were like, well, holy hell, you know, who is that?”

“The wildest show I saw there was Iggy Pop. He climbed up on top of the speaker stack, almost to the ceiling. His chest was bleeding, he’s completely out of his mind, and he wouldn’t come down.”

Kevin Wommack, musician and manager/publisher, remembers the Armadillo as a vital part of his entry into the music business. “My brother and I were touring and actually playing really young. I knew Hank and his assistant Killer. The reason we had so many shows there, I would just go and look at the calendar go. ‘I don’t see any support there. We’ll take that one.’ When we weren’t playing, I actually worked there. I ran spotlights, worked making nachos, selling t-shirts. If I wasn’t working, I was there watching the show. A lot of what I do, you know, comes from the base of what I learned working there, watching Frank Zappa or Boz Scaggs, getting to sit and talk to them backstage. There were a lot of people working there. The kitchen, the bar staff, the bouncers, which were basically the same people doing the artwork upstairs, the P.A. staff, your back end people booking and running the joint. There were certain personalities, some leaders, and when we’d have a catastrophe happen, like the night when Ken Featherstone [an artist also worked security] was shot and killed in the parking lot while the Pointer Sisters were playing, everyone would pull together. The Armadillo was a community of people. And whenever there’s the Armadillo Christmas Bazaar, I see a lot of them back. It’s like going to your any kind of reunion with people that went to the war, where there you have this common thread. None of us made any real money. It was all because we loved it.”

“Eventually, by the end,’ remembers Tolleson, “they had paid off the debts and were a bit in the black and probably could have continued for some period of time, except for the fact that the property owner, he and his sisters wanted to get their money out of the property. So that necessitated a sale. And our crowd couldn’t raise the money to buy it — a million dollars at that point in 1980. This was before the. the Chamber of Commerce, the people in this town who had the money and power understood what the music business was about, what the entertainment industry was about, or what it could become or what it meant economically.”

So the end drew near, the shows more sporadic, and for the final shows at the end of 1980, the Dillo returned to the country-roots-rock horse that brung them: A Lubbock night featuring the Flatlanders and the Supernatural Family Band.; Gary P. Nunn, Steve Fromholz and Jerry Jeff Walker, Delbert McClinton, and for New Year’s Eve, Asleep at the Wheel and a reunited Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen.

The final night was sentimental booze and drug-fueled sendoff. Ray Benson remembers taking the stage again after Cody’s set and playing until the wee hours of the morning, wrapping with Leadbelly’s “Goodnight Irene” and walking home alone at 4 in the morning. Kirchen recalls serenading a sea of empty beer cups after everyone had left, a cowboy song written by a friend called “When the Sun Sets On the Stage.” You can almost hear it.

At some point early on the first day of 1981, the Armadillo World Headquarters locked its doors for good.

I asked Kirchen, in all his years traveling with Commander Cody, if he ever encountered another venue like the Armadillo. I barely got the question out. “NO! No, no, no, no, no. Really! There were other places that have varieties of acts.”

“But nothing with a vibe and a whole culture and a proud image… I mean, I wanted to move there! We played the Fillmore’s. the Avalon Ballroom and all around the country. There was nothing like the Armadillo.”

“What an education, what a breadth of entertainment crossed that stage,” marvels Joe Nick Patoski. “Frank Zappa, Commander Cody and Freddie King. Are there three acts that could have less to do with each other? The Armadillo succeeded for all the wrong reasons. And the sad thing is it towards the end, it really had succeeded as a business. My thirty-five-year-old son remarked, ‘It seems almost dreamlike.’ And, you know, it kind of is. If you look at a certain time and what was out there and what came past you because you were here, and the Armadillo was here, it’s pretty f**king remarkable.”