This Week in Texas Music History, the queen of the boleros enchants the Texas-Mexico borderlands.

Episodes written by Jason Mellard, Alan Schaefer, and Avery Armstrong

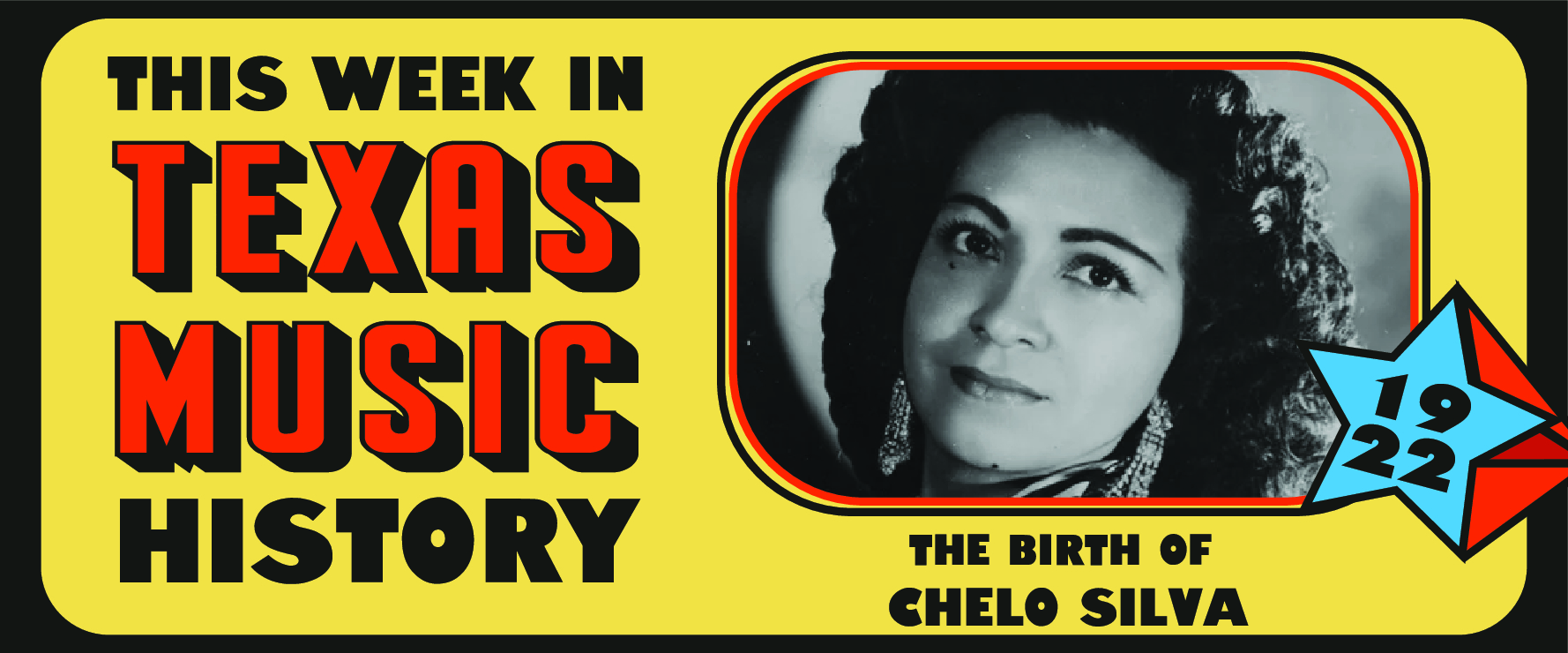

The Birth of Chelo Silva

Jason Mellard from the Center for Texas Music History at Texas State University

On August 25, 1922, singer Chelo Silva was born in Brownsville. She began performing in local groups as a teenager and in 1938 sang at the very first Charro Days celebration, now a Brownsville institution.

In her youth, she also performed with and was briefly married to Américo Paredes, who later became a prominent Southwestern folklorist. When Silva’s star rose, though, she shone on her own. In 1952, she cut her first records with Discos Falcon in McAllen and eventually released seventy tracks on the label, gaining fans across Texas and Mexico. In 1955, Silva also joined up with Columbia Records, giving her a greater commercial platform in the U.S.

Silva was a master of the canción romántica, her smoky, melancholy voice perfectly capturing the bolero spirit.

Living the night life of her songs, Silva gained a reputation for being risqué in stage patter and performance. Nightclub audiences loved it, but she also courted controversy in the Lower Rio Grande Valley while going on to larger and larger stages across the United States and Mexico. As such, for a long time her Brownsville hometown muted her public memory.

Scholar Deborah Vargas estimates that, despite her commercial success through the 1980s, there may have been as few as five official pictures of Chelo Silva in circulation during her professional career.

As Vargas notes, “the more successful and popular she became as a singer, the more excluded she was from the canon of borderlands music.” There are few printed stories on Chelo Silva from the period that don’t allude to her coarse language or love life. But, the records she left behind remain undeniable, and her devil-may-care persona and bold expressions of artistic freedom have won her new audiences in the 21st century, the queen of the boleros returned to her rightful throne.

Sources:

Manuel Peña, Musica Tejana: The Cultural Economy of Artistic Transformation. College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 1999.

Juan Cartos Rodriguez in Laurie E. Jasinski, Gary Hartman, Casey Monahan, and Ann T. Smith, eds. The Handbook of Texas Music. Second Edition. Denton, TX: Texas State Historical Association, 2012.

Deborah Vargas. Dissonant Divas in Chicana Music: The Limits of La Onda. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2012.