DISCLAIMER: The following article reflects views of the author and the author alone. Anything other than historical fact should be dismissed strictly as non-canon from a Wu-Tang Fan.

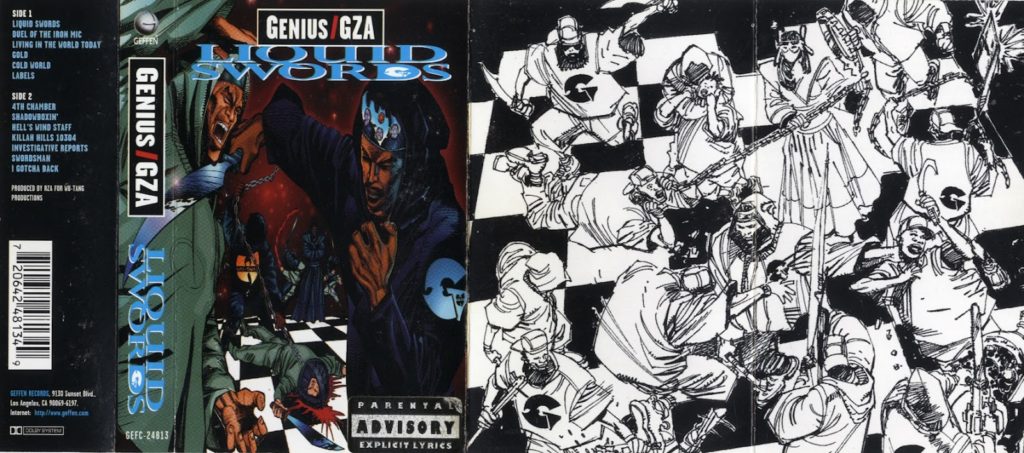

Twenty-five years ago, Geffen Records released the second solo album from Wu-Tang Clan co-founder GZA, Liquid Swords. With its extensive use of film dialogue samples, free association wordplay, and an undying atmosphere of grit, Liquid Swords has since entered the pantheon of greatest hip-hop albums, not only of the mid-’90s or from Wu’s expansive discography, but as a historic standout in the genre as a whole.

“I used to read a lot of nursery rhymes, and I learned a lot of those rhymes word for word. I would go to an aunt’s house, and she would let me play music, and she had The Last Poets album. At that time, albums didn’t have explicit stickers on them, so some of the songs had profanity on them, and I was moved by that. I would listen to those songs, to the flow, and I’d balance it back and forth with the nursery stuff I had. A year later I moved to Staten Island. I had a few DJs in my neighborhood that would play music in the streets. There was no hip-hop yet, there were just DJs that were playing disco, funk and pop music, and we would gather round, go to the parks and dance and enjoy ourselves. I would often take trips from Staten Island to the south Bronx, which is originally the first place of hip-hop. I was only around 11 years old, and sometimes RZA would come with me. The DJs and MCs there were way more advanced than the neighborhood I was coming from. It was just a culture that I was moved by, and I knew that was my calling…For us, it was just a passion and a hobby; it was something that is so much a part of my makeup. It was something I loved so much, we didn’t know it was going to change or revolutionise the world as a music genre. But if you think about it, [hip-hop is] something that children are attracted to immediately: even a lullaby – “Hush little baby don’t say a word / Papa’s gonna buy you a mockingbird” – that’s rhyming. When children hear that, they gravitate towards that faster than they would R&B or rock and pop, because it’s spoken word. It’s all art when you look at it – it’s a way of expressing yourself. Kids started doing hip-hop and rhyming and break dancing, and stopped being in gangs, so it was a powerful tool to get kids off the street and stop them from hurting each other.” (2015 Guardian interview with Mogwai’s Stuart Braithwaite)

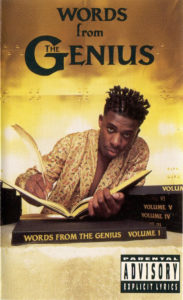

Throughout the ’80s, FOI (later All in Together) displayed early ambitions to diversify roles and talents, with each member of the trio eagerly trying out time in the spotlight both on the mic and behind the tables under varying stage names. Grice (a.k.a. “Allah Justice”) and Jones (a.k.a. “Ol’specialist“) would take the train from Brooklyn out to Staten Island to rendezvous with Diggs, and once the Wu-Prototype was assembled they’d borough-hop and rap battle in an effort to dominate New York City. They used a ruthless group dynamic, a tactic that would later define Wu-Tang’s success. Diggs’ Staten Island network of rappers steadily grew. In 1985 he formed the DMD Posse alongside childhood friends Clifford “Method Man” Smith, Jr., Dennis “Ghostface Killah” Coles, Corey “Raekwon” Woods, Jason “Inspectah Deck” Hunter, Lamont “U-God” Hawkins, and turntablist Selwyn “4th Disciple” Bougard. Though Grice had already dropped out of high school in his sophomore year to focus on developing his verbal skills, he continued (and still continues) to nurture his love of science and pursuit of knowledge, an academic quality that lent itself to his fitting self-description, The Genius.

The oldest of the three cousins, Grice was also the first to land a record deal, signing with Cold Chillin’ Records at the turn of the decade. Cold Chillin’ had helped launch the careers of Biz Markie and Big Daddy Kane on their respective 1988 debut albums, as well as the debuts from both Kool G Rap & DJ Polo and Masta Ace, introducing the burgeoning “East Coast hardcore” style to an audience outside the Big Apple. With Biz Markie recognizing Grice’s talent, the prospects looked good and The Genius was ready for his first exam.

“Clan in da Front”

The Forge Before Liquid Swords

Following the victory that was Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), the Wu-Tang Clan redefined success in hip hop by broadening their impact through solo contracts across several labels, with Ghostface on Epic, Dirty on Elektra, Method Man on Def Jam, and GZA on Geffen. RZA’s plan for complete domination of the music industry was officially in full swing, with a stipulation that “All Wu releases are deemed to be 50 percent partnerships with Wu-Tang Productions and each Wu member with a solo deal must contribute 20 percent of their earnings back to Wu-Tang Productions, a fund for all Wu members”.

The first solo effort out of the gate came in 1994 with Method Man’s Tical. RZA produced the album in full, save “Sub Crazy” (produced by Chambers turntablist 4th Disciple) and “P.L.O. Style”, produced by Meth himself. It’s been speculated by some that Tical came first due to Method Man’s perceived celebrity status, with some fans considering him to be the breakout star…judge for yourself in this clip below.

Regardless, Tical emphasized the haunting style that made Chambers great, even including the only track cut from Chambers, “Meth vs. Chef”, an example of RZA’s method for choosing who would appear on each track, by making the members battle one another (in this instance Raekwon against Method Man) over the beat in question. Clearly, the group dynamic was still key to Tical‘s success despite it being a platform for Method Man, with appearances from both RZA and Inspectah Deck amplifying the magic on “Mr. Sandman”. The post-release remix duet, “I’ll Be There for You/You’re All I Need to Get By”, featuring Mary J. Blige, reached #1 in the R&B singles chart for three weeks straight, earning Meth, Mary, and RZA the 1996 Grammy for Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group.

Next up was Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version, released in late March, 1995. Produced again mainly by RZA, The Dirty Version gave Ol’ Dirty Bastard (ODB) the extended platform he’d always needed for his “fatherless style” of sing-shout rapping with its hour-length. And though Return introduced the world to several new Wu-Tang affiliates and gave Dirty airplay with “Brooklyn Zoo” and “Shimmy Shimmy Ya”, the focus was on ODB’s wild vocals rather than the atmosphere. But RZA made sure to keep GZA’s gift in the limelight, giving him a feature on one of Return‘s most succinct and strong offerings, “Damage”.

The final predecessor to GZA’s debut was Raekwon’s August ’95 release, Only Built 4 Cuban Linx. OB4CL marked the first album since Chambers to be produced entirely under RZA’s direction, and witnessed the participating Wu-Tang members adopting organized crime personas, re-popularizing “mafioso rap” after its creation by Kool G Rap in the ’80s. Presented as sonic film of sorts, Cuban Linx was executive produced by Ghostface Killah, who monopolized features as resident guest “Tony Starks” (Ghostface’s first venture into his Iron Man concept), while RZA made his first stride as “Bobby Steels”, and GZA, ever the academic, masquerading as “Maximillion”.

Given the slower, layered and polished sound of Cuban Linx, it was hard to imagine that RZA could string together a more impressive Wu-Tang “solo album”. But as we all know, we must beware the fury of a patient man.

Liquid Swords Unsheathed

“The only two albums I did with nobody fucking with me was Linx and Liquid Swords. I was on a mission. To make all those early albums took three and a half years of my life. I didn’t come outside, didn’t have too many girl relations, didn’t even enjoy the shit. I just stayed in the basement. Hours and hours and days and days. Turkey burgers and blunts. I didn’t know if it was working. But nobody could hear or say nothing, no comments, no touching the board when I leave. Everything was just how I wanted it.” (2005 XXL interview with RZA)

“It’s hard to say something is gonna be classic or not. But I can say that I felt the magic with that one. I actually saw it grow and come together, and felt that it was special as we were doing it.” (2008 Wax Poetics interview with GZA)

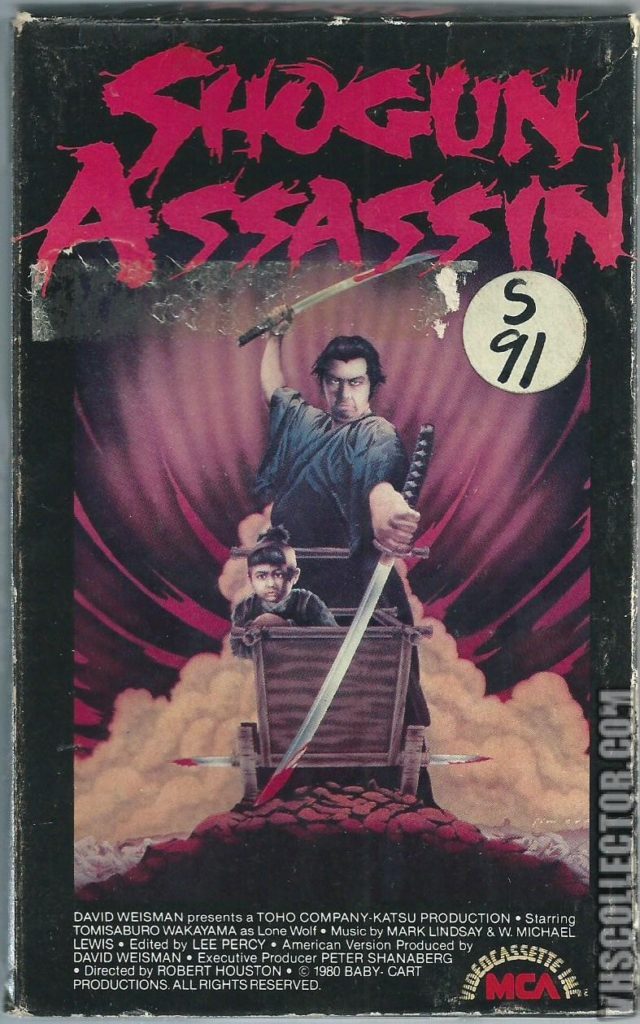

By summer of 1995, RZA’s Staten Island basement studio (a small, two-bedroom apartment) had become a 24/7 dojo for Wu-Tang’s growing roster of lyrical pugilists. RZA was finalizing the cinematic ambience on Cuban Linx, when he began working on a new batch of dark, hard-hitting instrumentals. Hearkening back to his earlier Wu roots, RZA packed the grimy baker’s dozen with compressed drum patterns, ’60s-’70s jazz and soul, and some of Shogun Assassin‘s most extravagant dialogue. The beats would be played on loop for up to two days at a time, with GZA perfecting his verses like a careful game of chess, one of Liquid Swords‘ central themes. Against RZA’s bleak grooves, GZA’s lyrics portrayed the day-to-day life for a criminal-minded Staten Island/Shaolin resident, often painting violence as a cartoonish metaphor (a common tactic in battle rapping) in a non-glorifying, brutally realistic manner.

Speaking on the “slow” recording process and his enthusiastic reception to RZA’s dark beats in a 2008 interview with Wax Poetics, GZA elaborates, “I don’t say slow in the sense that it necessarily took me a long time to finish what I’m writing. I mean, Raekwon and Ghostface can step in and record a song in about forty-five minutes. I on the other hand, would often go back and finish rhymes that I started. I would say I pieced things together [more] slowly then. Songs generally take me two to three days to write. Sometimes I take different sentences and put them together. For a few tracks on the album I remember, the beat would be running and it’d be four o’clock in the afternoon…RZA would leave and go to the city to handle business. He’d come home hours later and I’d still be writing the same shit I started when he left [laughs].”

RZA predicted that the 1980 film Shogun Assassin would match the artistic palette of the new tracks, and after an engineer returned with a rented copy, the film was shown to GZA who agreed that it fit the album well. The scenes chosen from Shogun Assassin were treated more like a “thread” coursing through the album rather than a specific theme, and for the first time in his production career, RZA experimented with incorporating digital sounds into his beats, finding MIDI tones that aligned with Shogun Assassin‘s brooding soundtrack. The overtly Eastern nature of Shogun Assassin gave both RZA and GZA an opportunity to revisit the martial arts and samurai overtones that had made 36 Chambers so idiosyncratic. The Scientist and The Genius took their time and soon enough Liquid Swords was ready to quench.

Based on GZA’s concept of a chessboard occupied by sword-wielders (owing itself to the album-wide boast of lyrical sharpness), former DC Comics penciller and Milestone Media co-founder/chief artist/creative director Denys Cowan designed the artwork for Liquid Swords, commissioned by GZA’s personal manager Geoffrey Garfield, a longtime comic book fan. True to Wu’s strategy of diversifying, GZA Entertainment‘s subsidiary GZA GrafX oversaw the creation of the digital cover art by Milestone color editor Jason Scott Jones and gave approval to the black and white ink piece from Prentis Rollins. And with Wu-Tang DJ Mathematics designing and rendering the sideways Wu-Tang “W” into a G, The Genius had officially caught lightning in a bottle.

The Legacy of Liquid Swords

“It has great songs, it’s not an ignorant album, it doesn’t sound dated. If you listen to it and compare it to what’s out now, it’s timeless….A lot of dudes write these street tales and they’re so gory, ’cause they think gory is visual … they’re so literal, and so street level. You know, like crack spots and whatever…I wanted to write something and take it to a level where nobody’s done it…Lyrically, it’s not my best work. Not at all. But the chemistry? Production? Overall, I mean, c’mon! RZA’s atmospheric production? Yes. It’s my best album.” (2008 Seattle Times interview with GZA)

Liquid Swords was released in the United States on November 7th, 1995 through Geffen records, and was met with instant critical acclaim surrounding RZA’s production and GZA’s unparalleled prowess as a wordsmith. It reached #2 on Billboard‘s Top R&B charts and an outstanding #9 on Billboard‘s USA 200. On October 8, 2015, the Recording Industry Association of America announced that Liquid Swords had earned a platinum certification for having sold more than 1 million copies. All of its four singles found success on the Top Rap & Dance charts, with “Cold World”, “Shadowboxin'”, and fan-favorite “Liquid Swords” all landing within the top ten.

From the critics’ point of view, GZA’s boast of being lyrically sharp assuredly hadn’t been a bluff. AllMusic, Pitchfork, and Record Collector all awarded Liquid Swords a perfect score; The Guardian, Q, and The Source gave four of five stars.

GZA had amalgamated all his observations and experiences from childhood to his time as a bicycle messenger into the present and spun them together into a sophisticated web of expression. He and RZA continued the Shaolin saga that started with 36 Chambers and created a worthy sequel with Liquid Swords, reaffirming Wu-Tang’s status as a ruthless foe to any contender, with GZA as Clan elder. Where Tical puts the horror aspect first, Return has a soul-singer feel, and Cuban Linx, a more lavish orchestral score. RZA’s matured production on Liquid Swords oozes with the energy of all three. On top of that, RZA’s inclusion of all nine original Wu-Tang Clan members on the record instantly evokes the group’s eponymous debut, more than the other solo albums at the time.

Between the transformation of RZA’s cramped living space into a recording mecca for musical martial arts, the continuous blurring of borders between real-life situations in the harsh cityscape of Staten Island and surreal, character-driven scenarios in Shaolin, the interstitial prevalence of cinematic dialogue (that has become just as quotable as the verse’s lyrics), and GZA’s incredibly well-calculated rhymes, Liquid Swords is rightfully considered one of the greatest hip-hop albums of all-time and one of the finest installments in Wu-Tang Clan’s colossal catalog.

Track by Track

Even if you’ve never seen Shogun Assassin, you could probably guess that the first sounds on “Liquid Swords” comes from the movie’s introductory scene, albeit with some of the fat cut out of it. What’s impressive about this is how seamless RZA’s synth work bleeds out of Shogun‘s soundtrack and into the Willie Mitchell samples that steer the beat. It’s always a ton of fun seeing this performed live; once the crowd hears, “when I was little…” they go friggin’ nuts. As the album opener, title track, and most successful single, “Liquid Swords” is one of the ultimate hype-up songs in ’90s hip-hop. Even according to GZA, it’s “just braggadocios. It isn’t meant to stand for anything. I’m talking about my skills and how I’m better than the rest.” Bonus points on this for the callback to the mid-’80s FOI routine, “when the emcees came, to live out the name…”

The Genius’ top pick, “Duel of the Iron Mic” jumps to another early scene in Shogun Assassin where the title target challenges the willing protagonist. It’s another case of the dialogue being thought of as part of the lyrics to the song, where you can recite it better than the verses (at least for me). The piano beat is dark but slick as hell, giving Shaolin its character as an ubran stylized R-rated Gotham. With what may be the shortest hook in Wu-Tang history, “Duel” also features Liquid Swords’ only appearance from Ol’ Dirty Bastard, who delivers the concise hook in his trademark slur. The posse cut energy is great in this one, with some solid stuff from both Masta Killa and Dreddy Krueger. The use of dynamics is a notable step up in RZA’s production’s given the volume range between the intro, GZA’s bars, ODB’s bombastic vocals, Inspectah Deck’s buildup that explodes into the track’s finale. Such a crowd-pleaser, (myself included).

As with “Liquid Swords”, the cadence of “Living In The World Today” is another remnant of ’80s hip-hop hooks, adapted from “if you listen to me rap today, you be hearing the sounds that my crew will say. And we know you wish you can write them, we’ll don’t bite them, well okay…,” transforming into a rallying Wu-Tang anthem. It’s a prime example of RZA’s ability to walk a thin line between the spooky, beautiful, and hazardous with his sample choices. Method Man’s elasticity against GZA’s discipline makes for some amazing chemistry on tape.

“Gold” has an entirely treacherous feel to it, apt given its subject matter of street hustling and RZA’s sporadic horn stabs. Ascending legatos depict the slums of Shaolin as a malicious hub of troublemakers. Especially with Meth’s intro and collaboration with GZA on writing the hook, “Gold” almost sounds like it was cut from Tical. This one will put you right in the environment of RZA’s basement studio.

Reappearing after two tracks of absence, Shogun Assassin kicks off “Cold World” with an oddly heartwarming piece of dialogue compared to its predecessors, and then launches right into another pseudo-sweet minor groove similar to “Living In The World Today”. GZA considers it, “just another dark, gritty street tale…another inner-city story“. In addition to the icy soul-inspired hook (interpolated from Stevie Wonder’s “Rocket Love”), the wind samples are a brilliant touch to “Cold World”, and just subtle enough to make you forget it’s there from time to time.

With RZA’s chromatic chops regulating the main orchestra groove, “Labels” is another grisly puff of the chest for GZA. And though partially inspired by he and RZA’s negative early experiences with records labels, GZA explains its true origins in his passion for wordplay. “I wasn’t deliberately trying to write a song dedicated to problems with labels and so on—I just threw ‘Cold Chillin’’ in there because they were an established label at one time. It actually started when I heard my friend say: ‘Tommy ain’t my boy!’ Then it just kind of clicked in my head to use ‘Tommy’ and ‘Boy.’” And that, ladies and gentlemen, is why he’s The Genius.

Living up to the expectations of its name, “4th Chamber” sounds like an unreleased rock-tinged B-side from 36 Chambers, with RZA hopping on the mic along with Ghostface Killah and newcomer Killah Priest. Always the introspective modest type, GZA purposefully saved his verse for last, mimicking his belief that, “it’s not even a GZA song to me—it’s a Wu-Tang song…This song, the guest verses, the video, the crowd response, all turned out perfect for this one.”

“Shadowboxin’” has to be my personal favorite song on Liquid Swords. The soul organ sample, turntable scratches on the dialogue, and bookend Method Man verses are all so well packaged together. “Shadowboxin'” might be another case of a Wu-Tang Clan song released under the guise of a solo effort, as GZA admits, “I think I was actually [just] the filler for that song anyways [laughs]. It always seemed more like Meth’s track. I remember RZA telling me I needed to get on it, so he put me in between. It’s an incredible song though, and I love performing it. It’s just another emcee lyrical joint with crazy smooth cadences.”

The beginning of “Hell’s Wind Staff / Killah Hills 10304” reminds me a lot of the soundscapes from Cuban Linx, and was recorded by the GZA and Killah Priest on GZA’s new portable ADAT recorder while the two were walking around Staten Island recording at will. Between roaring motorcycles, banging forks, and more, the layers build into something incredibly cinematic, also reminding me of later Beatles’ “Day in the Life”. GZA confirms the similarities to Cuban Linx’s Cosa Nostra ethos, clarifying that, “it’s a street story, but not told in a regular street way. I’m talking about slanging on the block, but not just your average street dealer. These were more sophisticated cats. Some of it came from a documentary I saw on the infamous Pablo Escobar. He was sending judges intimate photos of their wives and things like that. I think this is [probably] my first real Mafioso track. It’s like a dense, short film.”

As with “Killah Hills”, “Investigative Reports” taps into the Cuban Linx school of sonics, weaving a subdued string loop against the sparse bass and drum loop, and highlighting both Raekwon and Ghostface front and center. U-God and GZA hold their own, and other than that, it’s a pretty straightforward Wu-Tang Clan posse cut.

I feel like “Swordsman” completes the soothing-macabre trilogy that started with “Living In The World Today” and continued with “Cold World” but what makes it an outlier is how much more the groove is based around the pounding drums. It’s a banger and Killah Priest brings the necessary skills. Nuff said.

The album’s first single to be released, “I Gotcha Back” is another of my personal picks and includes some of Liquid Swords’ most quotable lines. You gotta love RZA’s dedication to chromatic ascensions and inversions in his sampling, always capturing that minor-second Jaws-type tension. The chorus is so fierce and GZA doesn’t need any backup to get through the verses, no surprise when you learn that the first verse quoted is a short rhyme written for one of his nephews as a cautionary tale. “When I said, ‘My lifestyle so far from well, could’ve wrote a book called Age Twelve and Going Through Hell.’ [it was] for my nephew who was twelve at the time, and whose father, my brother, had been locked up since ‘88…It’s a shame because…both nephews of mine, ended up getting in trouble for ringing out shots and are both doing time right now. It’s kind of ironic…the whole song is a sad irony to me now.”

A clear example of RZA’s style that would later influence Kanye West’s “chipmunk soul” formula, “B.I.B.L.E.” feels like the hot shower you’ve desperately needed after a long night in the cold, rainy Shaolin. Regarding his absence on Liquid Swords‘ swan song, GZA cites a strong desire to include Killah Priest on the album and that once Priest was secured, “he said he could cover the whole track, so we let him do it.” It almost sounds saccharine compared to the twelve tracks of gloom that precede it, but with its big heart, deep spiritualism, and sincere message, it’s a gorgeous piece of art that, in GZA’s own words, “ends the record out brilliantly.”

Liquid Swords in the World Today

As timeless as it is, Liquid Swords is undeniably a snapshot of New York in the 1990s. And though GZA’s continued to hone his talent is on the whole, nothing has seemed to match the tenacity of Liquid Swords in the twenty-five years that have passed for this erudite, vegetarian chess jockey. With his educational Netflix series Liquid Science and Showtime’s Wu-Tang Clan: Of Mics and Men, the legend of GZA and the Liquid Swords has been spun for generations to come. The record still sounds great and as one of the behemoth rap albums from New York in the 1990s, presaged the production of future releases from Jay-Z and Notorious B.I.G., further lending to its heavily-referenced reputation.

It’s one of few albums I can listen to all the way through and not want to skip around, and having seen GZA perform the entire album live, I can tell you it’s something to behold. So dive back into this ’90s time capsule and keep the spirit of Wu-Tang alive for the children with Liquid Swords.

–Jack Anderson