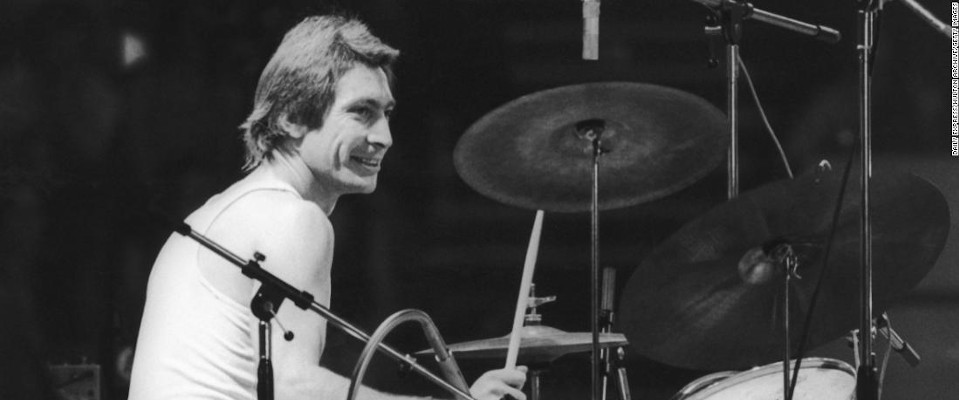

The Irreplaceable Charlie Watts

by Jeff McCord

Since Charlie Watts died, my mind keeps flashing back to a brief discussion I had with a friend a few weeks earlier, back when the news first broke that Charlie would not be joining the Rolling Stones on the latest leg of their tour. We were discussing their upcoming (rescheduled) Austin appearance, and I commented that I didn’t see how they would even sound like the Stones without Charlie. He strongly disagreed.

My friend is an experienced musician with many bands under his belt, so his reaction surprised me. For me, in a lifetime of listening, and taking an open-minded approach to all kinds of rhythm-based music, there has been one constant blocking the entrance. If the drummer isn’t locked-in, I just can’t go there.

Drummers occupy this weird netherworld in music. Many don’t know a C sharp from a B flat, or how to improvise (really, the less they do of that the better). In general, they’re not big on songwriting. And they’re the butt of countless jokes (“What kind of people hang around musicians?”). But they couldn’t be more vital.

Drummers (and, yes, even creatively programmed drum computers) are the foundation of everything else that happens, and while there are extraordinary players behind the kit in every genre, the best often barely get noticed. They’re not out front posturing, stealing the spotlight. But they’re the reason you’re feeling the music. Their glue is holding everything together and making your body move. They literally are making the music happen.

This is why so many great jazz drummers become bandleaders. Or why both Lennon and McCartney told the same story: sharing looks of wide-eyed amazement the first time they rehearsed with Ringo Starr, how he gave them something they didn’t know they were missing. Keith Richards repeated many times that he never had to think about the rhythm when he wrote. He knew Charlie would know just what to do.

Charlie Watts was a bit of an enigma. He didn’t consider himself a great musician and often talked about how he was limited because he never really learned to play properly. A fashion devotee and jazz fan, he seemed aloof at times, apart from the rest of the band. Yet at other times was right with them for their drugs and other excesses. He didn’t particularly like touring. But he loved to play. New Stones records have become scarce, to say the least. Yet in their decades of making music, it’s impossible to think of a single moment Charlie called undue attention to himself.

When you do pay attention to Charlie on the Stones recordings, though, there it is. The ever-so-slightly behind-the-beat syncopation, the rim shots, the skin-tight snare. At times he swings, at least within the confines of rock music, almost like a shuffle. Other times it’s a pounding blues beat. And often, it’s what he doesn’t play, the pauses and delayed entrances that create such drama and tension. He didn’t just accompany the Rolling Stones. He made them better.

A lot of recent obits have dredged up the story of a drunk Jagger calling Charlie’s hotel room to ask “Where’s my fucking drummer?”, and of Charlie showing up at Jagger’s door to punch him in the face. “Don’t ever call me your drummer,” said Watts. “You’re my fucking singer!”

I couldn’t agree more. Jagger and Richards are among the all-time greats in rock and roll. Their accomplishments are without peer. But they didn’t get there alone. The truth is that, long in the tooth and well into their career coda, the Stones haven’t sounded like their heyday for a couple of decades now. Still, I will likely be on hand one more time, if COVID allows, when and if they hit the Circuit of the Americas in November. I know the show will be a real spectacle. Top-notch players will be backing them up. But Charlie is gone. And, for me and so many others, the Rolling Stones will never be the same.

— The Rolling Stones (@RollingStones) August 27, 2021