The early eighties Austin band reforms 38 years later and re-releases their 1984 album

By Jeff McCord

We all have certain moments in our past we wish we could revisit, step back into and somehow relive the thrills, sights, and sounds. This explains the preponderance of band reunions.

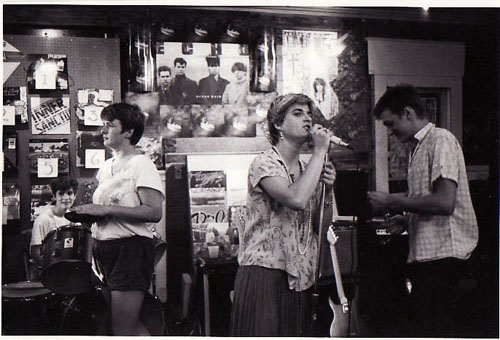

For Mellissa Cobb, Tim Mateer, John Perkins, Gretchen Phillips, and Jamie Spidle, that target date seems to be a brief slice of the eighties, 1982-1985, when a delirious post-punk scene in Austin included an almost unclassifiable band: Meat Joy.

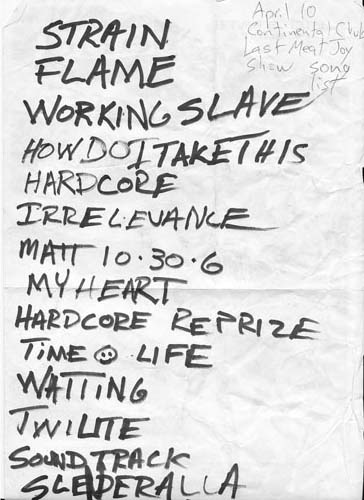

Meat Joy played their final show at the Continental Club in April of 1985. That is, until now. Despite its members being spread out around the country (and Canada), Meat Joy is reuniting for a pair of shows in Austin (October 19th at Cheer Up Charlie’s, and October 21st at The Museum of Human Achievement in East Austin’s Canopy studio center). And on October 13th, they are re-releasing their impossibly rare vinyl album from 1984.

Why?

This isn’t a ‘glory days’ type scenario. Meat Joy won some early Austin Chronicle music awards, but they didn’t achieve as much notoriety as some of their peers. And it wasn’t an instance of first-band nostalgia, either. Most of the members had played in previous groups.

And they have gone on to many other pursuits. Mellissa, who has a Ph.D. from Berkeley, played in the Delinquents and had an Austin band called Stick Figures prior to joining Meat Joy. She went on to front another eighties mainstay, Black Spring. Gretchen would form the pioneering Girls In The Nose and Two Nice Girls. John went into acting, changed his name to Hawkes (because of another John Perkins in the SAG), and has starred in many films and TV series (including “Deadwood” and an Oscar-nominated turn in “Winter’s Bone”). And Jamie, who started in Austin’s Buffalo Gals, would go on to drum for Nice Strong Arm, an LA band called Cowboy Nation (featuring Rank and File’s Chip and Tony Kinman). She currently plays in a LA band called Songs By Thom.

Yet to a person, they all say Meat Joy was the one.

Part of this was the times. It was an undeniably exciting moment in the history of Austin music. The catalyst, the punk rock venue Raul’s, had already shuttered, but dozens and dozens of great bands and venues sprang up in its wake.

“That time here in Austin, Texas,” recalls Tim, “with Gary Floyd [the Dicks] and Randy ‘Biscuit’ Turner [the Big Boys] as our den mothers, telling us to go out and start bands and that, ‘you can do this’.”

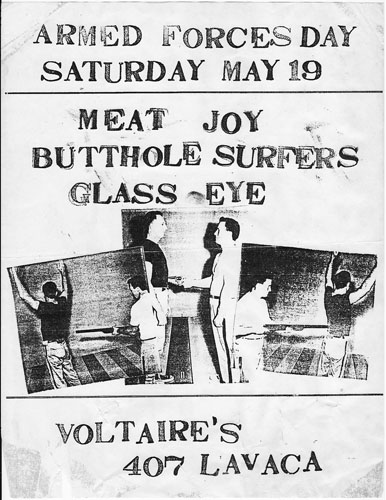

Newcomers Scratch Acid (the precursor to Jesus Lizard) and the Butthole Surfers were taking over. Venues like the sweaty firetrap Voltaires Basement and roadshow maven Club Foot were catching on. Exciting new bands surfaced most every week – the DIY spirit was infectious. The burgeoning ‘New Sincerity’ scene was on the horizon. And Austin mirrored what was happening elsewhere. Important bands of the era like Gang of Four and New Order were all playing in Austin.

“At that time,” Tim continues, “People were coming out of film school, writing good stuff, making music, movies, and it was all happening in that same scene. Whereas in some cities, San Francisco, New York, you know, those scenes were all separate. We were immersed in it. It was a generous and generating time.”

“I remember seeing Biscuit just going about his day,” says Jamie. “I lived right near the university and he would get stopped so many times by people wanting to speak to him. And I’d always just do a little head nod because I didn’t even want to bother him. He’s such a phenomenon, you know?”

“For me,” Gretchen recalls, “Being an out lesbian in 1982 in a band also with men was particularly transgressive to me. The fact that the men are so important to me and such great friends, and the fact that the experiences of our music, our rehearsals, our records, and our shows were so unlike anything else I’ve done. All of these things were really important to me about being who I am, being with other people who are being who they are. We get to be together in this sort of idealization that I had around human beings expressing themselves. And there’s no hostility. There’s a lot of encouragement.”

It’s an irony of the Austin post-punk scene. Fury and rebellion still streaked the music, but the scene was loyal to each other, sharing and giving.

“It was people who were thinking in very interesting ways,” offers Mellissa. “Local bands that were doing really extraordinary things, very receptive to hearing things, and there was an intellectualism in the scene that I particularly thrived on.”

“Smart people,” John agrees.

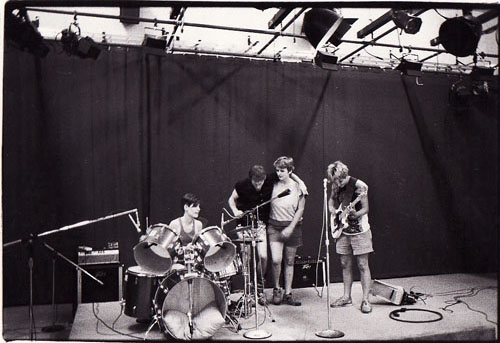

Like most groups of disparate people, Meat Joy fell together by happenstance. Their fame and longevity didn’t match some of their peers because they weren’t as easily pigeonholed. They had a tight-knit, yet herky-jerky sound. Co-ed, part punk, part folk, they started their shows with full-on improvisations and passed out lyrics to their audiences so they could sing along. Their enthusiasm and creativity made them irresistible, even if no one knew quite what to make of them.

Tim recalls their beginnings. On a friend’s recommendation, he had gone to see Mellissa in Stick Figures. “He says ‘You got to see this gal’. She sings in German. She’s singing Bertolt Brecht songs. And boom, I started stalking Mellissa. Our friendship develops. We ended up starting a student organization, and we would put out a little magazine. The girls were playing, and we had just shown up to help put magazines together and stuff, and I got invited to jam. I don’t play any musical instruments per se, and it’s like, what? ‘You can do this and take these two sticks in a block and beat on it and here, try this out.’ Truly to be invited in like that as a non-musician was a joyous moment.”

“Teresa Taylor (aka Teresa Nervosa), our first drummer, later of Butthole Surfers fame, and I were girlfriends,” recalls Gretchen. “She introduced me to Mellissa. Teresa, Mellissa and I jammed that summer of ‘82, and then we got a house together. And when the boys… we would have these great sprawling jam sessions in the front room. I have cassettes that have lasted remarkably well. It’s solid improv.”

Jamie, who replaced Teresa on drums in 1983, agrees. “We were just learning how to play our instruments together and really wanted to play some shows. We had this rehearsal space that we also lived in and I got a drum set, I think because I would go to Raul’s all the time and [see] the band D-Day quite a bit. I went up and I asked their drummer David for drum lessons. And that’s how I started. Also Brian Beattie from Glass Eye, one night he was going to be rehearsing, but he was like, ‘Oh, I better do some laundry. Here, I’ll teach you a drum beat. When I come back from the laundromat, I’ll jam with you.’ And I practiced that one beat over and over. When he came back, he played it with me and I was like, ‘I love this!’.”

Gretchen continues. “I had moved to Austin from Houston, so I was going to see everything. I had my sort of worshipful relationship initially with Jamie and Mellissa from seeing them play out before I did. I had played music prior in Houston, but Meat Joy was my first band in Austin to play, to be gigging at the cool clubs.”

“I’d had about a month in a band only,” John recalls, “So Tim and I came in with the least amount of musical experience. One thing that was really unique about this band is that we have such a wide range of musical talent. I don’t really consider musical talent in a traditional way, I suppose, but we have a really wide range of people who are really great on their instruments and people who are not as great on their instruments all the way up and down. But I think it’s really about listening and I felt like we were good listeners. That really helped us along. Usually, bands are all of the same level, either great or best players, and this band has such a variety and I think that’s what makes the sound unique. And when one member is missing, it doesn’t work. It just doesn’t work.”

“We had a band rule,” Tim remembers. “Any individual in the band could bring an idea and we would act on that idea before we talked ourselves out of it. We were not allowed to make any negative comments about it. It’s like, ‘No, let’s try that’. And that was part of how it goes in so many different directions because every individual brought ideas and words, music and combined them.”

This leaderless approach also made the band difficult to pin down.

“Once in Dallas,” John explains, “We sent our tape player out in the audience to record the show. But [on the tape] we also heard comments and [it was] either off that tape or someone telling us firsthand that someone who never seen Meat Joy before turned between songs to their friend and said, ‘Is this a lesbian Christian band?’ I then [started] saying, ‘We’re not just another lesbian Christian band.’”

And Meat Joy’s communal spirit extended to its audiences. A Meat Joy show was an event. They would have after-parties where fans would help design t-shirts.

“We would hand out drumsticks at the end of the set for the audience to join us with this percussion jam,” Gretchen recalls. “We handed out the LP covers for other folks to decorate, and we would have record decorating parties.”

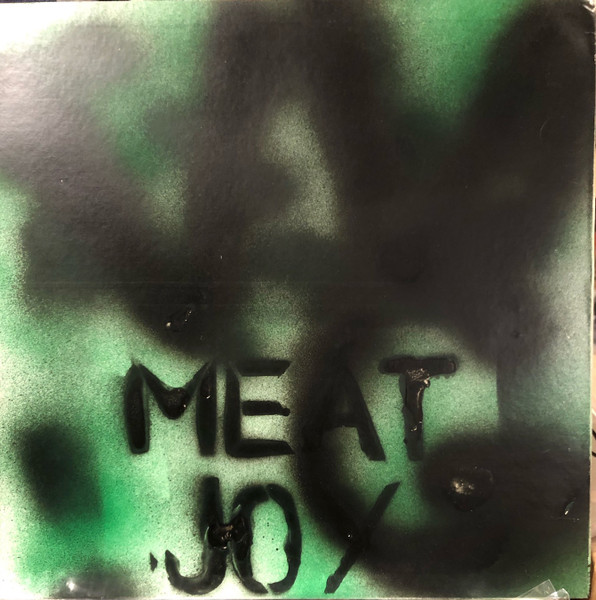

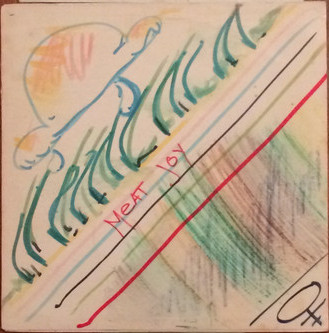

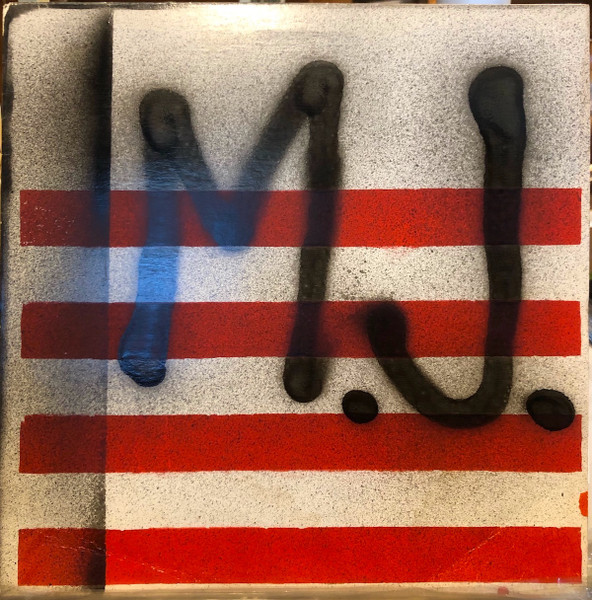

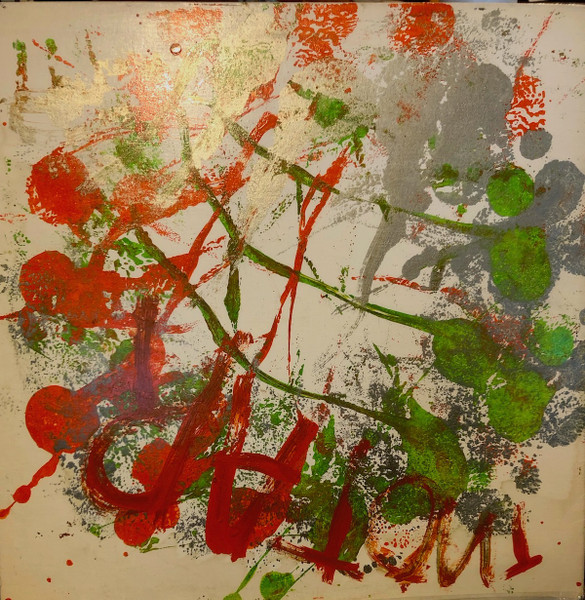

In addition to eight different front covers, each copy featured hand-illustrated back covers from the band and their fans. These are long out of print and collector’s items. Keeping in the same spirit, the reissue of the album will also feature four different covers.

Hand-drawn Meat Joy artwork

So how did this reunion get started?

Mellissa explains. “I had moved to Chicago and just really started wanting to do music again. And I was trying to do it independently, and I felt so isolated and alone. In the meantime, John, [in] several phone calls expressed in such a beautiful, touching way how much he missed Meat Joy and how much he enjoyed that experience. It invaded my dreams, songs were coming up in my dreams because of this beautiful, nostalgic, lovely feeling. It just spurred me on. And I asked everybody if they wanted to reform.”

“I liked Mellissa’s line when we were getting together to rehearse in May,” says John, “where she said we decided we couldn’t live without each other.”

The band managed to corral in Austin for the first time since 1985 this past May.

“It sounded at first like we hadn’t practiced in 38 years,” John recalls. “And then we found our way.”

They’ve spread out again at the time of our Zoom call. But prior to the shows in October, the band will reconvene here for another week of rehearsals.

All this effort, jump-starting a band that last performed in 1985, not to mention the work it takes to re-release an album, seems like a lot for just two shows. Is something more planned? More shows? New Songs? New recordings?

Instinctively, they all wait for John, who likely has the busiest schedule, to answer.

“Oh, I just,” John realizing what is happening, “Let’s see how we enjoy the experience and if people are interested, we’ll continue to play the shows.”

Gretchen takes over. “I feel like this incredible response that John has had seems so intelligent and well measured, which is ‘why don’t we do this and see how it goes?’”

[They all laugh.]

She continues. “It’s so awesome. Like, oh, okay, why don’t we do this instead of ‘I had a great date and I’m looking forward to us getting married and having five children’. It’s like, ‘Let’s just have some sex, okay, and see what happens.’ I don’t know. Maybe something will be generated. You know, let’s just see how we enjoy it.”