Zambia’s Jagari leads the comeback of the Zamrock legends

By Jeff McCord

In some ways, it’s the most unlikely of stories. Northern Rhodesia, a British protectorate in South Central Africa, gained independence in 1964. Renamed Zambia, the country buzzed with a newfound freedom.

Yet in other ways, the story of WITCH makes perfect sense. Independent on no, it was already too late for Zambia’s teenagers, inundated with pop radio and Melody Maker. They were obsessed with British and American psych-rock and R&B. Among them was a young Emmanuel Chanda, who would soon become known worldwide by his chosen nickname: Jagari.

It’s been quite a day for Chanda and his reconstituted band WITCH. Thanks to numerous bus breakdowns, they rolled into Austin at sundown after a 24-hour drive, with barely enough time to check into their south I-35 hotel before their show at the Far Out Lounge. Yet he still agreed to our interview, asking me to join him at the hotel. I expect he is exhausted but he doesn’t show it. He’s friendly and welcoming.

I had been looking forward to talking with him for some time. From early Zamrock comps to the 2012 WITCH compilation (We Intend To Cause Havoc, on Now Again records), his band has been in heavy rotation at my house. And now the reformed WITCH has released Zango, a big favorite on KUTX, and their first album in nearly forty years. I thank Chanda for seeing me under the circumstances, I call him a legend, and I mean it.

He just laughs.

“I like the title “legend’. I think legend must be synonymous with the money that it attracts. I’m on the way to that. I might have the fame, but I don’t have the money. Yeah, It’s coming.”

It’s a modesty and optimism Chanda has always shared, from the beginning of his time in what he calls the “Copperbelt”, Zambia’s mining industry that fueled the economy and lured prospectors from neighboring countries.

“My elder brother brought me up, worked in the mines and he worked night shifts so that the radio was always on in the evening. There was no one there to say, ‘Why you listening to the radio?’.”

So Chanda absorbed it all and daydreamed.

“There was this trend [when] the guardian or the parent leaves the employment of the mines,” he says, “They allow you to take over the place. I think my elder brother had hoped that I would go there and work in the mines, and I was almost lured by the idea. I liked the discipline. I liked the uniform and things like that. But I was told I couldn’t keep my afro hair. And that’s the cut there. No way. So I put that aside.”

Chanda had no idea what he wanted to do, yet he had an unsubstantiated faith that things would work out. Rushing out of school with a change of clothes packed to jettison his school uniform, he headed to the social club where local groups practiced and eventually got asked to jam.

“I had my notebook where I wrote the lyrics. It was not easy to get the British and American accent. I remember trying. I was singing ‘Sympathy for Devil’ and the people around me liked it, but I never, ever heard words like ‘troubadours’, so I made up my own words, which I didn’t understand.”

WITCH began like most groups, a cover band trying to mimic the records they loved. But before videos or the internet, they could only rely on records they could find or could hear on the radio, and the translations got a bit crazy. And Chanda’s overactive imagination led to a wild stage presence. For the most part, with few bands coming through Zambia, he was left with only magazine photos to understand how a rock star fronted a band.

When people started calling him “Jagger”, it made Chanda uncomfortable. So he changed his nickname at first to “Jaggery”, then to the more ethnic ”Jagari”.

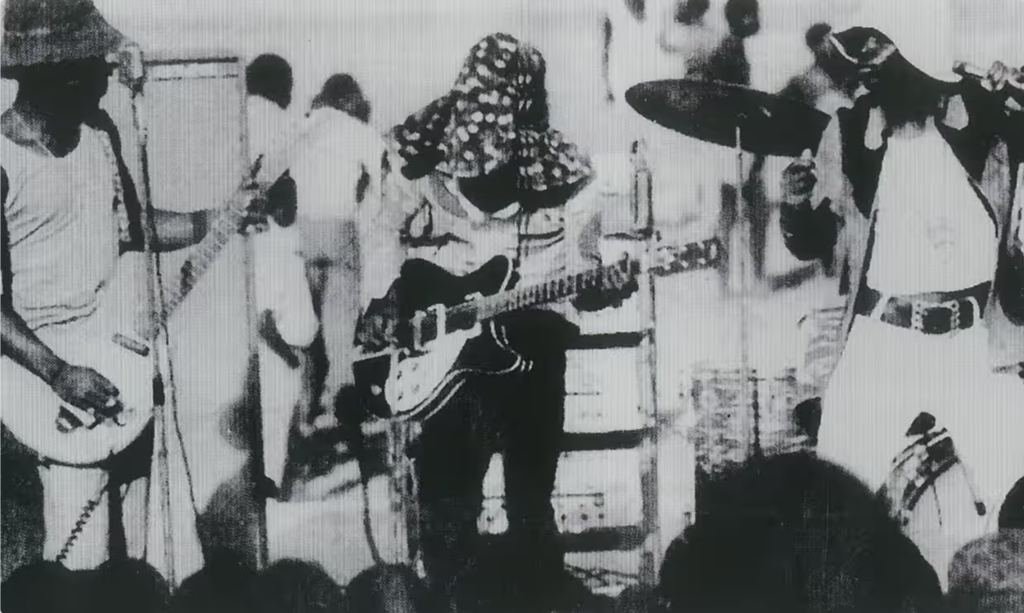

Caught up in the fever of independence, Zamrock took hold in Zambia, and Jagari and WITCH ruled the roost. Thousands began turning out to see the band, and WITCH was fashioning their own unique sound. On their early recordings, you can hear them imitating the sound of UK bands like the Stones and Animals – bands themselves imitating American blues artists – or American artists like James Brown or Hendrix. Through each filter, things would morph in unexpected ways.

“We have 72 ethnic groups in my country,” Chanda says. “While it’s not a very good situation in terms of understanding one another, the first president tried so much to unite everyone by saying ‘One Zambia, One Nation’ as a motto. That helped and shifted people from one province to the other so they intermarried and forgot about the ethnic initiative. In terms of music, the fusion of rock and roll is because of the influence of America and Europe. But we were Africans, you know? [There were] limitations. Apart from the English syllabus and things like that, we also use a simple scale pentatonic scale as opposed to the tonic scale. We have smooth, simple rhythmic patterns that entice people to dance rather than the harmonies you emphasize. There’s a lot of repetition in our songs, in the lyrics, the call and response repeated over and over.”

So WITCH became a wholly unique blend and an irresistible powerhouse act in Zambia. They played all over the region, made albums, and lived the life of rock stars. That is, until everything crashed.

By the mid-seventies, Zambia was suffering on all points. The country was in the midst of an economic crisis, and despite their recent independence, citizens were under increased authoritarian rule. Curfews meant bands could only play during the day, and if anyone wanted to go out at night, they were locked into dance clubs until the morning hours. Zamrock began to fade, and Chanda left WITCH to limp along for a couple of more records without him. By the mid-eighties, due to the burgeoning AIDS epidemic, almost all of Chanda’s original bandmates were dead.

“The HIV and AIDS pandemic just swept the floor for a lot of people, Not only musicians across the board, teachers died. There was stigma and there was also no medicine. So a lot of people died.”

Chanda tried his hand at teaching and eventually turned to the only thing he could think of to make a living: the mines. As far as he was concerned, mining gemstones was now his life. The stage was nothing but a distant memory. Decades went by.

But in 2012, Now Again Records, a reissue label led by Egon Alapatt, issued a massive 4-CD set of WITCH’s music, and suddenly crate diggers everywhere were discovering the hidden delights of these former Zambian superstars. One of them was Gio Arlotta, an Italian London-based journalist and music blogger who sought out Chanda, and told the incredulous singer he wanted to make a documentary on WITCH (also titled ‘We Intend To Cause Havoc’). The film is still in post-production, but Arlotta had another offer: he would manage and help Chanda assemble a new lineup to take the music of WITCH back on the road. (It was Arlotta who was shepherding the group and their broken-down bus into Austin.)

“It’s a very talented band,” boasts Chanda. “We have people from Bulgaria, from Germany, from the Netherlands, from the UK, from Africa, and we are playing together and they are younger. Most of them are much younger than me.”

Chanda is now 72, the afro hair is long gone, replaced by a colorful headdress. That night at the Far Out Lounge, he drives his young band through a set of polyrhythmic rock and R&B delights, drawing heavily from their new album, Zango. Jagari has been back in action for a few years now, but he still marvels at WITCH’s resurrection.

“I’m very grateful to God that he’s that he has given me another chance of a lease on life. I never thought that I would go back on stage. I’d almost given up, but I have not forgotten about my dream. My dream has always been that I don’t want to die with the little knowledge I have acquired. I would like to share my knowledge with the youngsters, my experiences and knowledge after being a teacher. I have thoughts to make the younger generation’s lives easier, and like they way just listen to by ear. That’s how you imitated bands. So my dream has been [that] Zambia should have a very nice school of music and an international standard studio where I can retire. That has been my dream. That dream, that dream must never die.”