by Jeff McCord

He was irascible, ornery. After getting out of the Navy, where he spent his time as an airplane mechanic, he was inspired to learn the guitar by a 60’s Lou Rawls concert: moved, not so much by the music, as by the number of women surrounding Rawls. He was almost indifferent to the stardom his remarkable string of songs brought him. And in 1985, when his new label, Columbia, got up too much in his business, he just quit. He would never release another piece of music.

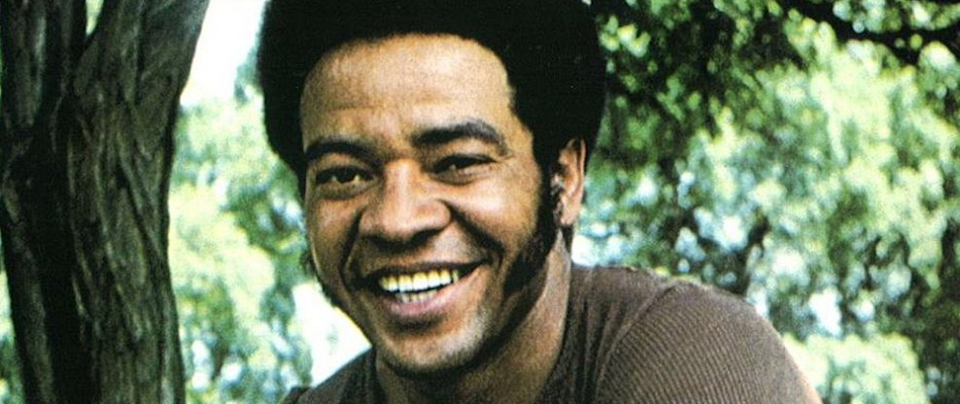

Yet Bill Withers, who passed away from heart complications March 30th at age 81, would leave his mark on American popular music like virtually no other ’70s soul singer. Motown had paved the way in the ’60s for mainstream acceptance of black music, and contemporaries like Al Green, Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin and Marvin Gaye were making their own groundbreaking music. Yet Withers, with his emotive, plainspoken tales of loyalty, lust, and longing, stood apart. “Lean On Me”, “Ain’t No Sunshine”, “Grandma’s Hands”, “Use Me” – who hasn’t taken these songs to heart?

Chance the Rapper tweeted “Aw man, Bill Withers really was the greatest. [These] are some of the best songs of all time.”

Questlove calls Withers the last African American everyman. In a 2015 interview, he said “Jordan’s vertical jump has to be higher than everyone. Michael Jackson has to defy gravity. On the other side of the coin, we’re often viewed as primitive animals. We rarely land in the middle. Bill Withers is the closest thing black people have to a Bruce Springsteen.”

Aw man, Bill Withers was really the greatest. Grandma’s Hands, Ain’t No Sunshine, Lean on Me, Use Me Up, Just The Two Of Us and obviously Lovely Day are some of the best songs of all time. My heart really hurts for him, it reminds me of playing records with at my grandma’s house

— Chance The Rapper (@chancetherapper) April 3, 2020

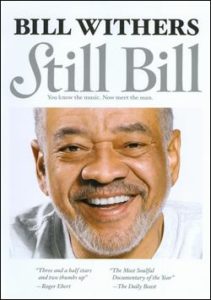

And he’s right, right down to the plain white t-shirt Withers wore to an interview for the 2009 documentary Still Bill (highly recommended, if you haven’t seen it). Devoid of over-arching themes, Wither’s work delved into the politics of the personal.

Born into the great Depression’s wake in 1938, Withers fought both a childhood stutter and the institutional Jim Crow racism in his hometown of Slab Fork, West Virginia. He would get out quickly, joining the Navy at age 17. Once out of the military, he worked as a milkman and later, as an airline mechanic in Los Angeles. He was thirty years old before he first picked up a guitar.

Writing songs between shifts, Withers would record a demo that found its way to a fledgling independent label, Sussex. They set up a session for him with producer Booker T. Jones (“Duck” Dunn and Stephen Stills were on the session, too). Jones would later reveal that Withers took him aside when he first arrived in the studio and asked, “Who is going to sing these songs?”

“He was expecting some other singer to show up.”

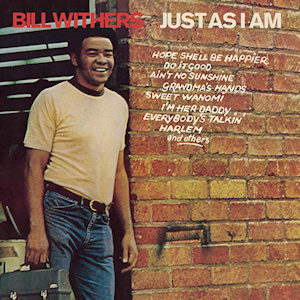

Withers would recount this in his song “Do It Good”, included on his 1971 debut Just As I Am. But it was the album’s first single, “Harlem” b/w “Ain’t No Sunshine”, that set Withers on his way. DJs immediately gravitated towards the lonely lament of “Sunshine”, with its repetitive “I know, I know” chorus. Supposedly written after Withers watched the Jack Lemmon/Lee Remick tearjerker Days of Wine and Roses, “Ain’t No Sunshine” would go on to sell over a million copies and earn Withers his first Grammy award. “Grandma’s Hands” would follow, achieving more modest success.

Withers would recount this in his song “Do It Good”, included on his 1971 debut Just As I Am. But it was the album’s first single, “Harlem” b/w “Ain’t No Sunshine”, that set Withers on his way. DJs immediately gravitated towards the lonely lament of “Sunshine”, with its repetitive “I know, I know” chorus. Supposedly written after Withers watched the Jack Lemmon/Lee Remick tearjerker Days of Wine and Roses, “Ain’t No Sunshine” would go on to sell over a million copies and earn Withers his first Grammy award. “Grandma’s Hands” would follow, achieving more modest success.

Withers would take over production for his follow-up album, 1972’s Still Bill, recorded during a break off the road with his touring band, the 103rd Street Rhythm Band. With its earthy, rough-hewed funk, and the triple threat of “Who Is He (And What Is He To You)”, “Use Me” and the iconic “Lean On Me”, Still Bill has achieved GOAT status as an indispensable addition to any record collection. The album would hit #1, and the generous support of “Lean On Me” has been used, and re-used, as the soundtrack for everything from two presidential inaugurations to 9/11 to the Coronavirus outbreak.

Yet despite all this success, Sussex was beginning to falter, and when it became clear the label could no longer pay its bills, Withers took it hard. He wiped the tapes of his latest album. “I was socialized in the military,” he told Rolling Stone. “When some guy is smushing my face down, it doesn’t go down well. Since I was self-contained and had no manager, my solution was to erase the album.”

When Sussex folded, Withers moved to Columbia but found the independence he had been previously granted a rare commodity. Over the course of a few more albums (including the uncharacteristically slick hit “Lovely Day”), facing the racial epithets of A&R men and fighting off such hare-brained ideas as getting him to cover Elvis Presley’s “In The Ghetto”, Withers eventually lost his taste for the game. The 1985 album Watching You Watching Me would be the last recorded music he released. He walked away and never turned back.

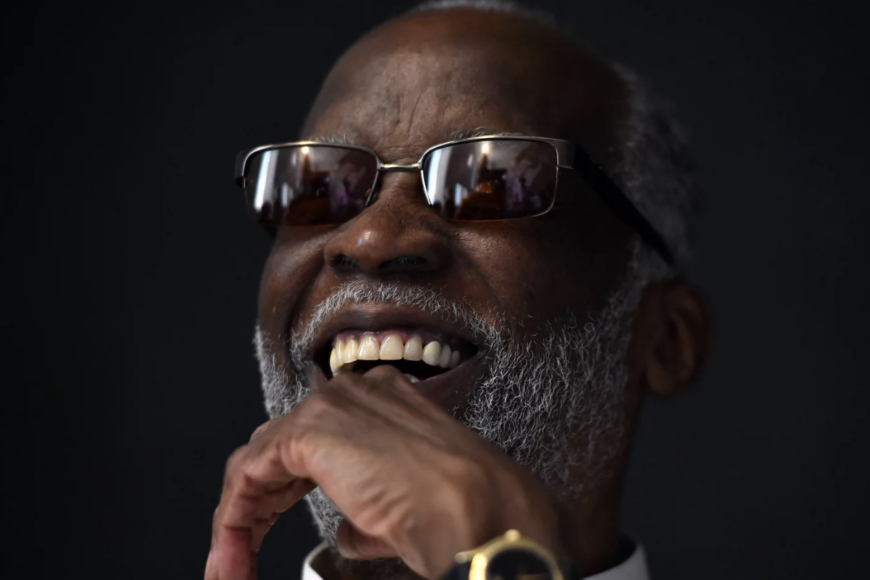

Not that people didn’t try to change his mind. With one exception, a 2004 private party for Detroit Pistons owner Tom Gores (Withers claimed his wife wouldn’t leave him alone), Withers never appeared on stage again. Yet as the mystery of his retirement and his historical status grew, the offers kept coming in, each one more fantastical than the last. Withers ignored them all.

Not that people didn’t try to change his mind. With one exception, a 2004 private party for Detroit Pistons owner Tom Gores (Withers claimed his wife wouldn’t leave him alone), Withers never appeared on stage again. Yet as the mystery of his retirement and his historical status grew, the offers kept coming in, each one more fantastical than the last. Withers ignored them all.

The filmmakers of the 2009 documentary Still Bill, with its culmination in a Bill Withers tribute concert, seemed to design their film in hopes of reversing that trend. (Spoiler alert: they didn’t.)

So this former airplane mechanic, happily married and comfortable from royalties and investments, went back to a quiet life. “I’m very pleased with my life how it is,” he told Rolling Stone. “ This business came to me in my thirties. I was socialized as a regular guy. I never felt like I owned it or it owned me.”

Support KUTX’s ability to bring you closer to the music. Donate today.