John Doe reflects on the band and their final album, ‘Smoke and Fiction’

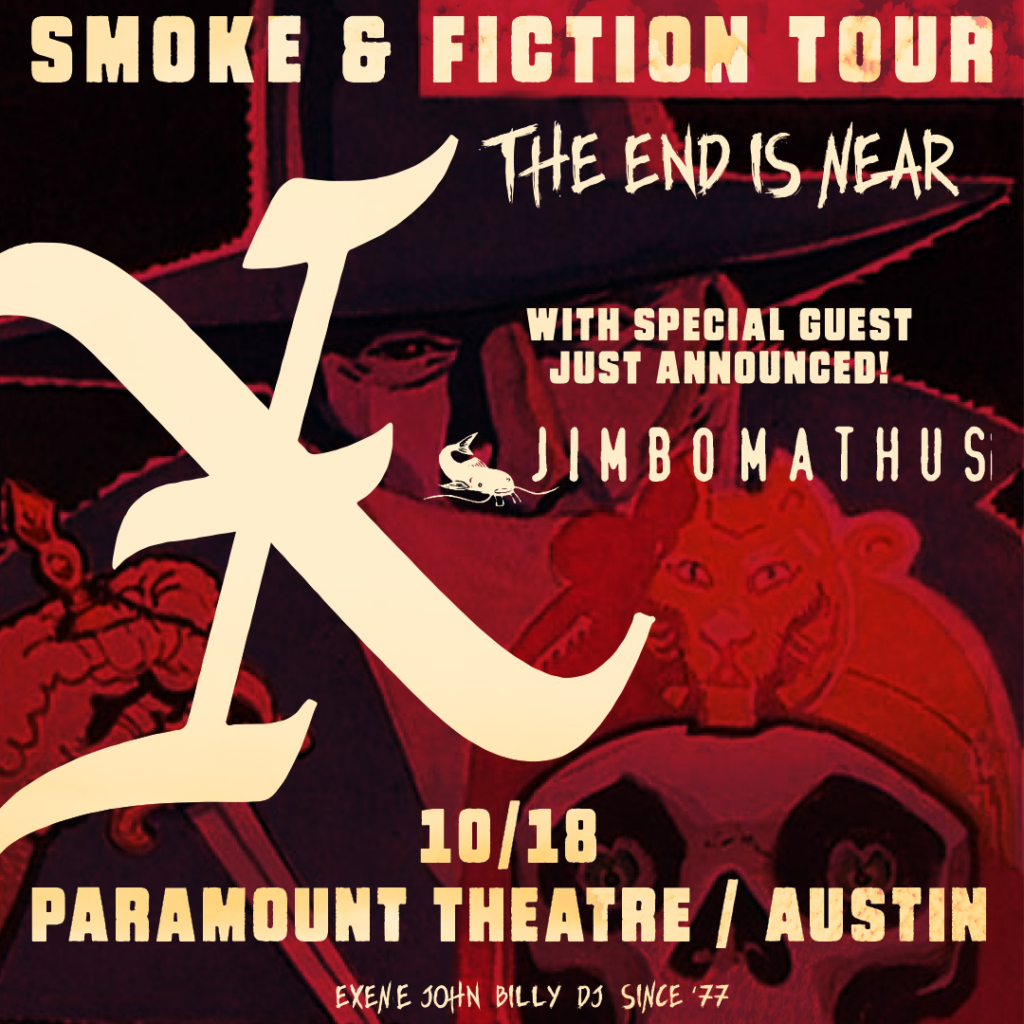

(Catch X in Concert Friday 10/18 at the Paramount Theatre)

By Jeff McCord

To the rest of the country, the notion of LA punk always seemed incongruous. The place was perfect, right? Never rains. Swimming pools, movie stars.

The city’s underclass knew differently.

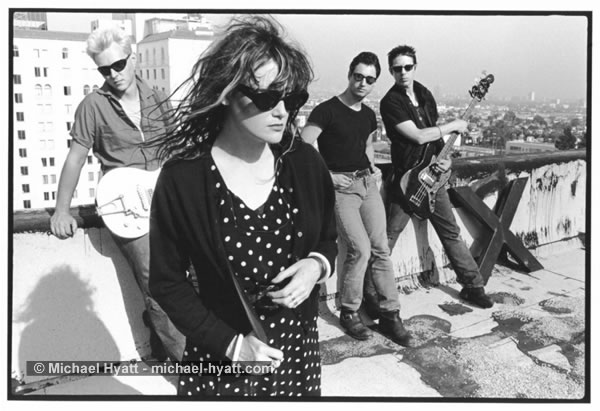

So it makes a certain kind of sense that the reigning band of the west coast punk scene was, and still is X, the LA quartet that started making their peculiar brand of urgency in the late seventies. “We’re desperate!”, they screamed on their first single. “Get used to it!”

Look at any list of the best albums of the eighties, and the band’s visceral one-two album punch, 1980’s Los Angeles and 81’s Wild Gift sit right there at the top. Sneering. Flies in the ointment.

Others, because of their outsized commercial success, may have had a bigger impact. But for over four decades, X has defined crucial American music.

It was more than blistering attitude – though there was plenty of that to go around. They had songcraft. A sense of what had come before them. Nothing felt half-baked, tossed off.

It still doesn’t. Released a few weeks back, their ninth album, Smoke and Fiction, takes up right where their 2020 pandemic comeback Alphabetland left off. Thirty five years since the original lineup had made a record, and it sounded like they’d just come back from a dinner break.

Carbon-dating the music of X has always proved difficult, in part because of their remarkable consistency. And there’s the unusual nature of their lineup.

“I was going to make it.”

That’s John Doe, one half of X’s lyrical brain trust, responding to the question of why the Decatur IL-born John Duchac ended up in Los Angeles with his police blotter alias in the first place.

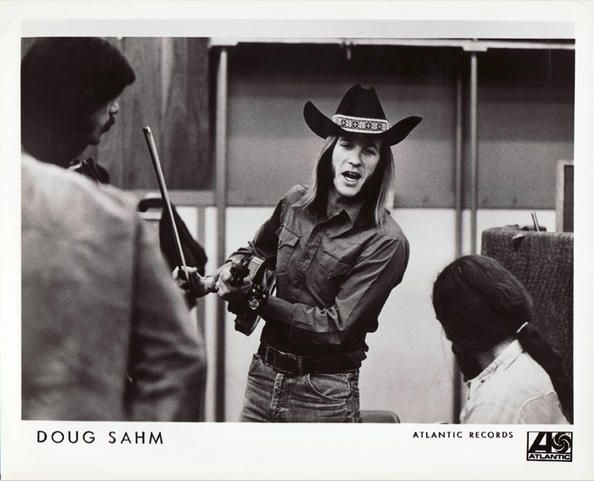

On a break from the Smoke & Fiction tour, John is back in his adopted hometown of Austin, where he’s lived since 2017. Over time, LA seemed to dispose of everything he loved about the city. Fondly remembering the many iconic X shows in the city with the likes of the Big Boys (as do we all), it seemed a natural choice to relocate. He loves Austin, and having him around, talking with him and understanding a bit about what drives him, what makes him tick, has been a real pleasure. He’s a great conversationalist, forthright, honest.

In addition to X, John has been part of celebrated side projects like the Knitters and Flesh Eaters, written (with Tom DeSavia) a couple of anthologies of the LA punk scene, acted in over 50 film and television productions, and released over a dozen solo albums.

But arriving in LA in the mid-seventies, he first met up with unlikely partners.

“There was a paper called The Recycler. You could buy, like, a refrigerator or a lead singer,” John recalls. He found a guitarist, not a punk rocker but an experienced veteran several years his senior.

“Billy [Zoom] played in R&B bands. He played with Etta James, he played with Gene Vincent the last year or so of his life. He brought in rockabilly guitar playing. Nobody played rockabilly guitar style or surf guitar in punk rock – well, Robert Quine, a little bit in the Voidoids. So, we were pretty traditional in that way.”

As for his future wife and songwriting partner? John met Exene at a poetry workshop.

“Beyond Baroque. It’s Tuesday nights and it’s still going on, an amazing organization in Venice. I think it was fate.”

At first, the relationship was purely personal. Exene wasn’t a musician.

“Exene had written [the poem] “I’m Coming Over” and she could sing it beginning to end,” John explains. “It was clear to me that she was singing a song. She didn’t have any chords, so I put some chords to it, and I said, ‘You know, I’m working with this guy Billy Zoom. And, it’d be great if we could play this song, we’ll give you credit and everything like that, it would be great.’ And she said, ‘Absolutely not!’ It wasn’t blackmail, but she realized this was the one thing she had that was valuable.”

“I could tell she had no intention of being a lead singer. She didn’t go to LA to make it. She went to get out of Tallahassee. A friend of hers was driving to California and needed help with gas money. But it was really clear to me that she had the power and the soul to front the band. I didn’t want to be the guy. And it turned out that that was a brilliant decision because nowadays we can kind of trade off. Singing lead doesn’t wear you out and it has variety built into it. And over time, we figured out how to sing together. I give Exene most of the credit for that because she hadn’t been in a bunch of cover bands and didn’t learn traditional harmony. It has this mountain-y, folk music kind of vibe.”

The last piece to the puzzle: drummer DJ Bonebrake,who joined after he left his band the Eyes.

Almost instantaneously, their punk energy and rootsy foundation made them a local phenomenon. Signing to the big independent label Slash, they brought in another unlikely partner – producer and keyboardist Ray Manzarek, from the very un-punk rock group the Doors. They clicked, and Manzarek would go on to produce the band’s first four albums.

Stuff happened, as stuff does. In 1985, John and Exene would divorce, yet carry on as musical partners. Billy Zoom, frustrated with the band’s lack of a commercial breakthrough, would leave the band in 1986, following the release of their fifth album. He wouldn’t return until 2008. In the interim, Dave Alvin, then Tony Gilkyson held down guitar duties. X would go on hiatus a couple of times, though neither would last that long. Exene would announce an MS diagnosis (later refuted), stir up conspiracy theory controversies on social media. But their gravitational pull was strong, and by 2008, the original four were back in each other’s orbit.

The new album, Smoke and Fiction, manages the sleight of hand they’ve pulled off before. X makes the difficult look so easy. Rob Schnapf’s production is strong and straightforward, and the recording took about three weeks.

“You shouldn’t spend more time than that unless you have some grand opus that you want to dream you have,” says John. “We did the basic tracks in three days, and then Exene and I did our vocals in about four. Billy put his guitars down in maybe less than a week, and then Rob mixed it with his engineer in 8 or 9 days, something like that. Maybe ten. One song a day.”

Painless, right?

“Not actually,” says John. “No. [It was] a really hard record to put together. Just writing, rewriting, rehearsing, touring, relearning.”

And though none of them knew when they were working on it, they dropped a bombshell when they announced the album’s release: Smoke and Fiction would be the last X album.

“It became clear as it developed,” John explains. “Exene wrote a prose piece, ‘Big Black X’, and she didn’t know what to do with it. But DJ and I had some chords, and I had an idea for a chorus, as we were trying to fit the words into a more lyrical form. We made a chorus that was way too epic and strident, the lyrics were, ‘We knew the future and also the gutter’ – an arm raised in a solidarity fist. Maybe Joe Strummer could have gotten away with that, but we couldn’t. We didn’t know the future. That’s bullshit. But we did know the gutter, so we switched that around, just made it simpler and it all fit together. In the writing of that and in ‘The Way It Is’, maybe ‘Ruby Church’ and the title song, it had this reflective quality to the lyrics.”

“It wasn’t nostalgic because we don’t, I mean, if you look up nostalgia, it’s, it’s a pretty damning definition. You’re trying to make things what they weren’t. You’re also longing for that moment in time, like any other moment in time isn’t valuable, and that’s that’s no good. But it was reflective.”

At this point, the band has established a solid writing relationship. John and Exene each bring in what they’re willing to share, the rest of the band contributes, they reject, rework and rewrite until it works.

“[Exene and I] share a brain of some sort,” says John. “It’s a beautiful thing. We’re really fortunate to have worked together for so long.”

With titles like “Sweet Till The Bitter End” and “Winding Up The Time”, X seem to be working towards a conclusion, even as their energy remains undimmed. Yet Smoke and Fiction sounds vital as ever. So why stop?

“It’s being realistic,” John explains. “And wanting to go out on as much of a high note as we can. Billy is 76 years old. I’m 71. Billy sits down now because his knees are kind of shot, and he fancies himself as Les Paul. There’s no hidden agenda. It’s just quality of life. I like staying home. I like being with my beloved, and so does DJ. It’s the grind of going in and out of hotel rooms, unpacking your crap and then putting it back together and driving for four hours, if you’re lucky, or maybe ten, because you have a ‘day off’, when you’re driving from Denver to Salt Lake City. You get so worn out. People will say, do you fly to tour dates or do you get on a bus? It’s neither. We have two sprinter vans because we’d rather put the money in our pocket.”

“Hopefully by limiting the number of [future] shows we will give people a reason to take a road trip or play two nights in New York or Atlanta, in 2026 or 2027, Hopefully we’ll do like 20, 25 dates a year. No one wants to be part of an organization where the wheels are falling off.”

X has been successful at controlling every aspect of their story. But time is beyond their reach. Maybe if they’d managed a bit more mainstream success, they might have been able to prolong their touring life.

“We are in a very sweet spot,” John says, “we’re all incredibly grateful. It’s either, people know of us, and it can be as much as, ‘They’ve saved my life’, literally. Or ‘I don’t know who the hell you are’. And that’s better than having a couple of hits and then just, ‘Aren’t you that band that had .. that outfit?’”

“I’m hoping that we make it to 50 years,” John confesses. “I would love it if Billy was around if we ever get into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.”

They’ve shared each other’s creative lives for 47 years, and they still clearly mean a lot to each other.

“We did our thing, and we didn’t compromise too much. There was quality in the playing and writing and we opened some people’s eyes to being individuals.”

Their genesis was long ago, but it defined them as a band and as individuals.

“If someone who’s 18 came up to me and said, I’ve only got 3.5 minutes, what was it like in 1978? Listen to ‘Big Black X’, because that’s got all the imagery of climbing up to go to Errol Flynn’s burned down mansion on a hill, the LAPD coming over in helicopters, setting Christmas trees on fire in Hollywood alleys, people grabbing onto the bumpers of a of a car and sliding down the street backwards on their leather jackets. It was fun. It was incredibly reckless, as you can be when you’re in your 20s.”

X are survivors, and they have left behind a real legacy. It’s difficult to picture the evolution of American rock music without them. (you can see them in action at the Paramount Theatre Friday 10/18)

“I’m glad the coach keeps putting us in,” John says, smiling. “It’s not like, ‘Oh, shucks, we don’t deserve it’ because we worked really hard, writing the songs we did and having, trying to just be more or less accessible without pandering. The songs that we write, they’re pretty traditional. It’s a verse and the chorus. I think Billie Joe Armstrong is a great songwriter. He can write a chorus like Tom Petty. Everybody sings along. That’s awesome. I can’t seem to manage that, and that’s cool. They do their thing, we do ours. It would be nice to have a big fat bank account, but we would have probably just wrecked ourselves.”