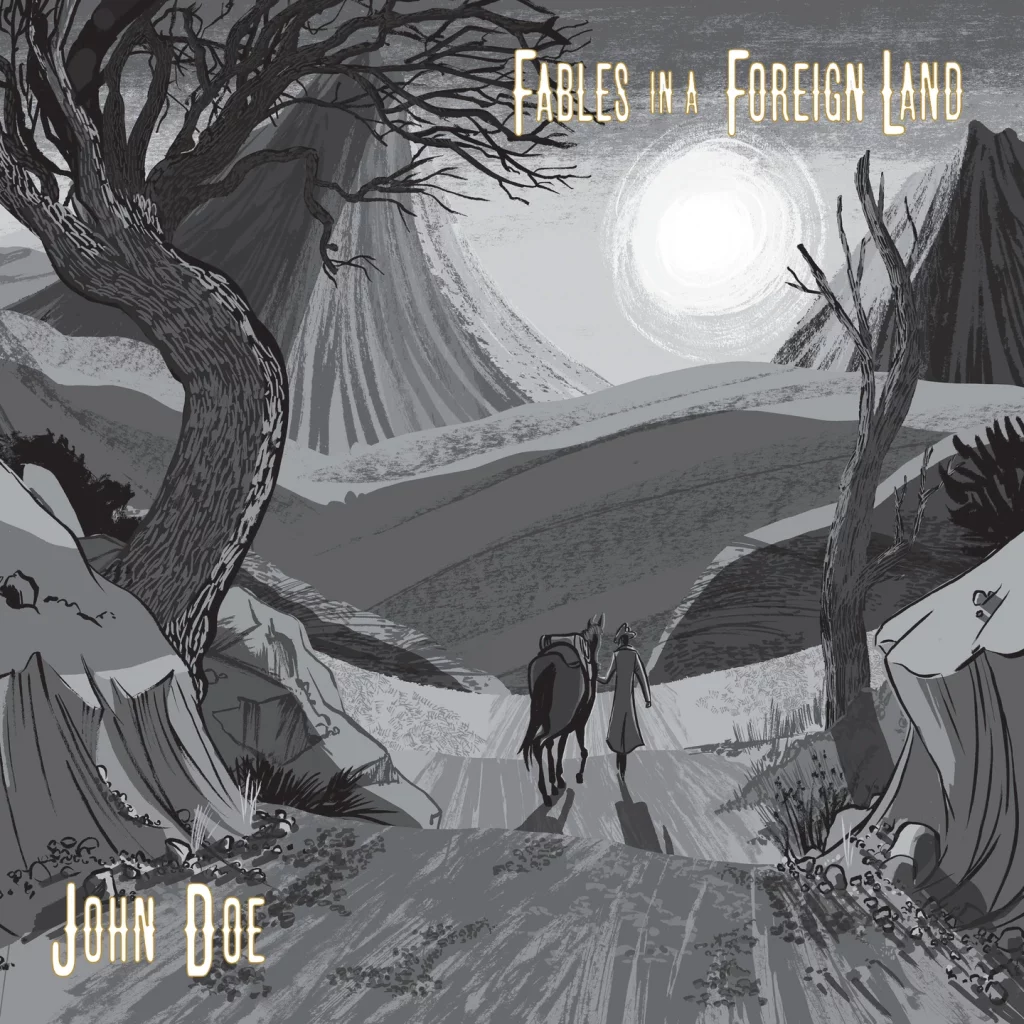

Fables In A Foreign Land is a concept record set in the 1890’s.

Given the long-term solidity of John Doe’s career, you might have missed the curveball in his arsenal. Fables in a Foreign Land, released 5/20 on Fat Possum Records, is a different kind of John Doe recording. In one sense, it’s unmistakably him, his omnipotent voice, his punk roots-rock sensibilities. Yet in terms of settings, both musical and otherwise, Doe is wandering new trails.

For one thing, the album, recorded live in the studio, is embellished only by a bare-bones trio. For another, the entire album is set in the 1890’s. “I’ve been saying it’s a concept record without the pretension,” says Doe, laughing, “But I try not to be pretentious about it. There’s no opera.”

While Doe, both with X and on his solo recordings, has explored characters in his songs before, this time there’s more of an arc and a sweep to his storytelling. Why this era, I asked him. Was it a longing for a simpler time?

“It’s a number of historical novels. There was one called Glory Land that was out a little while ago about an African-American sergeant when the military used to be in charge of Yosemite Park. And there’s my association with Michael Blake, who wrote Dances with Wolves, and a couple of other books that were set in the time of Custer. It’s not that [the era] was simpler. It was more elemental. You had to fight with elements that could kill you, or you could starve. And there’s a sense of adventure. And that’s another thing that fascinates me.”

Fables certainly did not begin like most albums. There was no theme in mind, or in fact, any kind of album at all. Through Exene, Doe befriended Willie Nelson bassist Kevin Smith, and at some point found himself convening on Kevin’s back porch with drummer Conrad Choucroun. “And I realized,” Doe explains, “after the third or fourth time, that, ‘Oh, we’re not doing this for anything.’ Which was a great realization. We’re just doing it so we can remind ourselves what we like to do.”

Yet a sharpened, dusty style emerged, and soon, songs came into focus; A down and out “Missouri”, the surreal tale “The Cowboy and the Hot Air Balloon” where a man steps out of a bar and is literally swept up into the sky. “Is this fate or is it a dream?” the cowboy wonders.

By the time “Never Coming Back” came along, Doe saw a clear theme emerging.

“I’ve always been a little fascinated with pre-industrial stuff, you know, being a lover of nature, being a lover of animals. I just had to be disciplined in order to bring it over the line. And it wasn’t that hard. I couldn’t make a full narrative from the beginning of the record to the end. But I really love bringing a cinematic kind of quality to it, just to give enough information so the listener can get in there and move around a little bit. It’s always hard to get songs together, but it wasn’t that hard to say, okay, here’s my theme and I’m going to do this.”

“Never Coming Back” also yielded a surprise. Doe had sent the song to his friend Terry Allen, no stranger to conceptual recordings, hoping to get some pointers on how to proceed. Instead, Allen sent him back additional lyrics to the song. Doe laughs at the recollection. “It was like my ego kicked in and I thought like, ‘Well, this song is done!’ And then the, you know, immediate other reaction is like, ‘Oh, crap, what if it isn’t?’”

There are a couple of other co-writes on the album as well. Doe dusts off a murder ballad Garbage’s Shirley Manson wrote lyrics to that he, Shirley and Exene originally recorded while X was on tour with the band. And Los Lobos’ Louie Perez contributes Spanish verses that flesh out the ridiculous braggart of “El Romance-O”. (See our pop-up video of Doe’s performance here)

But mostly it’s Doe’s words and Smith and Choucroun’s backbeat, an assemblage christened as the John Doe Folk Trio in the credits. “I sat on Kevin’s back patio just singing and playing out into the air,” Doe recalls. “So that’s how we recorded it, without headphones and just singing and playing into the air.” The air was a small room in Jim Eno’s Public Hi-Fi studio. “We had to pretty much do it live. If there was a bomb bass note or we sped up – and Conrad just doesn’t speed up, or if I sang a couple of bum notes, then we’d have to do it again. Steve Berlin, who also co-produced and Dave Way, who co-produced and engineered, could say, ‘Okay, well, maybe we can go to a different take just for that little section.’ They assured me that that’s what some old jazz records did. So we thought that was fair.”

There are a few guest musicians. Carrie Rodriguez contributes haunting violin tracks on a few songs, including “Down South”, of which Doe says “That was directly inspired by living here.” (John became an Austinite in the latter part of the last decade). “The Texas sky, when all those white clouds appear in the afternoon. Words and melody came together at once. And then, then I worked on the story part about sleeping on the ground.”

There are many such stories on Fables, encompassing survival, violence, gothic horror, and quiet moments of beauty.

“There’s a black horse in a photograph/ His mane blows in your face/ Your eyes are hidden/ Will you be taken away” begins “There’s a Black Horse”, which Doe says came to him long ago in a dream as a premonition of a breakup with a serious girlfriend.

“It was before I was John Doe,” he recalls. “She came from Alamogordo, New Mexico, and introduced me to Hank Williams. But as we were splitting up, I had this dream that. That she was just by this horse, and the man was obscuring her face. And I thought, Oh, I guess that means you’re leaving.”

And amid the mysticism, something else: a strong sense of mortality and spirituality surfaces time and time again. I tell him this surprises me.

“Me, too,” Doe laughs. “I’m definitely more spiritual than I was ten years ago. Maybe that’s just a matter of age. I think if you believe something going to happen, there’s more likelihood of it happening. The so-called coincidences that that seem to happen that I think are fateful. Exene and I moved to Los Angeles within, like, six months of each other. So, I don’t know, But I think it also had to do with the journey of this person [on the album]. He or she is off in the wilderness, and they’re saying, ‘Why me?’ They’re saying, ‘What the hell, God. I mean, have you forsaken me? I’ve been told all this stuff about, you know, you’re going to strike me down or, you know, I have to please you. So what’s the deal?’ Like in the song “Missouri”, there’s a reference to, ‘Let me down easy / But just let me go’. So that’s definitely cause I’m older. That’s okay.”

It occurs to me how the perils of the 1890’s can relate to today’s pandemic. I mention this to John.

“Yeah,” he says. “It’s odd that I worked on this whole thing and later, I was talking to my daughter about it and she said, ‘Wow, there’s a lot of similarities between then and now.’ And I said, ‘What do you mean?’ She said, ‘Well, there’s a lot of isolation, there’s a lot of fear, there’s a lot of loneliness.’ And it’s like, Yes! This is great! Thank you for telling me what I’ve been working on!”

[Hear excerpts from this interview on What’s Next with Jeff McCord, Thursday 5/19 at 8pm on KUTX 98.9]

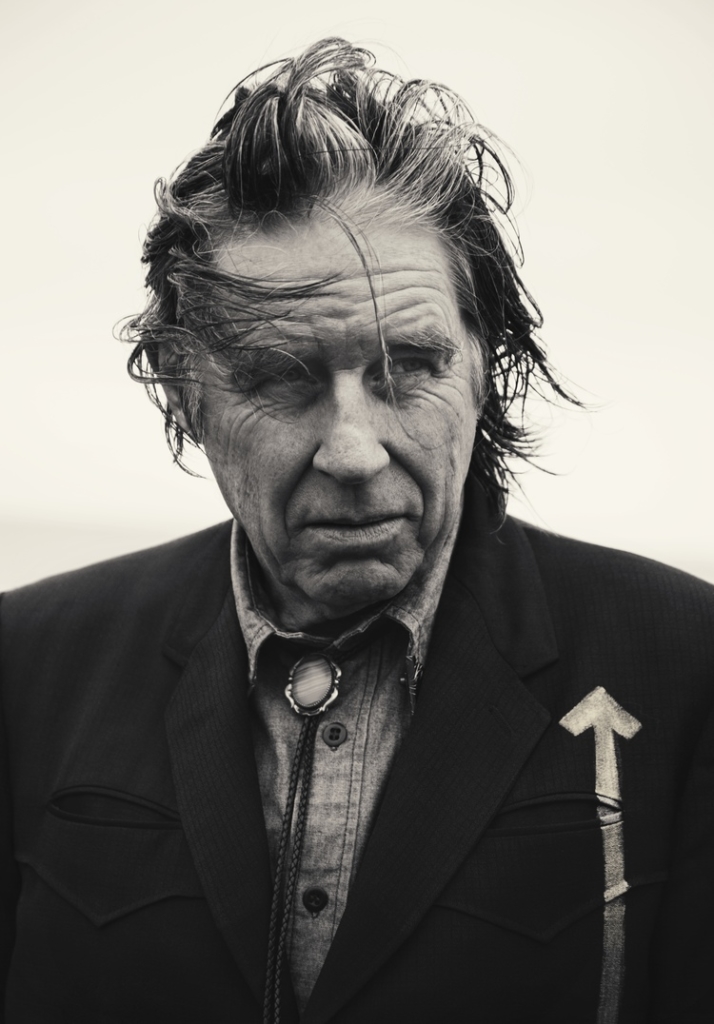

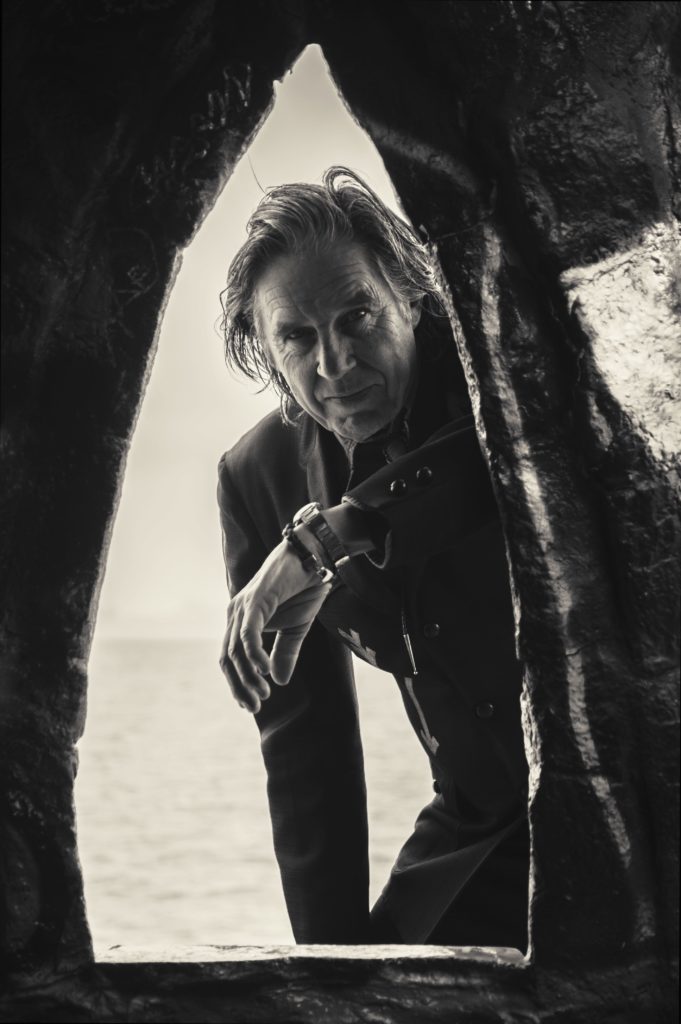

Banner photo: Todd V. Wolfson