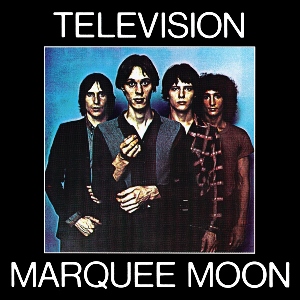

Television’s founder forged his own path (l to r: Fred Smith, Tom Verlaine, Richard Lloyd, Billy Ficca)

Tom Verlaine, who died Saturday at age 73, was one of rock’s most visionary guitarists. Just like the myriad angles of his playing and composing, Verlaine came at rock music through a less-traveled path. Much has been made of his early love of Roland Kirk, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Albert Ayler – probably too much. He might have played saxophone, but he was young. It’s not as if Verlaine, or Thomas Miller, as he was known back then, was in the clubs squalling free jazz.

But he was listening. Born 1949, into the pre-rock era in a suburb of Wilmington Delaware, of all places, he started his journey on piano, by all accounts a serious player with an early love for orchestral music. It wouldn’t last. He took up the saxophone, but when his twin brother started playing early Rolling Stones records, Miller fixated on the guitar sounds, the ways, like Coleman and Coltrane, the notes bent hard to the emotions of the players, and the ways the rules he grew up with were being quickly obliterated. He loved his saxophone, but he could see this guitar thing working out.

So he went for it, pulling along everything he had already acquired in his short musical life. By 1966, he was finding his voice and was ready to start a band, which he did with his friend Billy Ficca on drums. At boarding school, he met one Richard Meyers. They became fast friends with a shared passion for getting into trouble. College didn’t take for Miller, so he rejoined Meyers, now in New York’s East Village, and called up Ficca. The Neon Boys were born, and wouldn’t last long, but the three, already loaded up with original material, met guitarist Richard Lloyd and decided to give it another shot. The New York Dolls’ glammy pop ruled the roost, but something else was in the NYC wind: punk. They cut their hair, and shredded their clothes, Meyers took the surname Hell, and Miller, just to be contrary, named himself after the 19th-century French poet Paul Verlaine. They took the most ridiculous name they came across – Television.

They were anything but. Neither rank amateurs brandishing their DIY pride nor floor-staring gothy cynics, Television stood a breed apart. Verlaine had fashioned a serrated, strangled cry from his instrument. There wasn’t a hint of Keith or Chuck in his weird chording or his melodic scatterings. With the more conventional, but also talented Lloyd as his foil, their twin guitar assault melted the air. That alone would have drawn in the hordes. But there was so much more.

Verlaine had these lost, brittle songs. Emotional, complicated, they perched on the edge, as if the slightest breeze could break them apart. Some ran more than ten minutes long, others flew by in a burst. Raw, art school-ish, other times desperate, urging. “Prove it!” Verlaine screamed defiantly. At best, his vocals resembled a drowning man gasping for air.

Amazingly, they got the whole thing on tape. Marquee Moon stands as one of rock’s recorded pinnacles. An all-time classic. Not of its time, of its genre. Ever. By this point, Richard Hell had been replaced by Fred Smith on bass (poached from Blondie). Verlaine’s twitchy but undeniably arresting material melded melody and imagery into something inseparable. The guitar intro to “Friction” (yes, pure Coltrane), raises the hair on your neck. “I recall,” howls Verlaine on the title track, “Lightning struck itself.”

And then came the rest of Verlaine’s career, and the problems with peaking too soon. Adventure, the second Television record, with Verlaine and Lloyd squabbling, was a bit of a fizzle. A 1992 reunion album was only marginally better. Verlaine had a long and varied solo career, and made some excellent records, Tom Verlaine and Deamtime the most Televison-like. Others, News From the Front, Cover and a series of noir-ish instrumental albums brought home his early love of orchestrations. They could be playful, unpredictable. And he played on other people’s albums, did some production work.

But never again would lightning strike itself. Even the eventual Television reunions for festivals (mostly without Lloyd) felt somewhat perfunctory. Verlaine would joke in interviews about his lack of a post-Television career. Maybe he was OK with it, maybe not. But he seemed mostly at peace, putting out occasional records, continually scanning new musical horizons.

Verlaine arrived with an unheard talent and new ideas. His work lives on in the works of Steve Wynn, Nels Cline and many others. Patti Smith, a longtime admirer and onetime romantic partner, who Verlaine frequently accompanied, said this about his voice, in a way only she can. Verlaine, she says, “plays lead guitar with angular inverted passion like a thousand bluebirds screaming.” Let’s just leave it at that.