By Chase Karacostas KUT/KUTX E-mail Campaign Developer

I didn’t realize buying this record would reconnect me — and my brother — with my favorite album.

Vinyl records were little more than wall ornaments to me growing up. Hanging in a formation, they followed me up the stairs, trapped in paper sleeves inside glass frames, never to be heard, only observed.

They were my parents’ records. And the closest I ever got to them was when I packed them into boxes for a move six years ago. We had a record player, but it didn’t work very well.

The first time I heard a record live was 15 years ago. We’d gotten my father a record player that could burn the songs onto a CD for his birthday. I remember being 10 years old and watching him delicately pull one of his unframed records out of its sleeve and place it into the largest device I’d ever seen for playing music.

More than a foot tall, the record player dwarfed the iPod Shuffles, walkmans and alarm clock-CD players that defined my childhood up to this point.

But vinyl was still in decline back then, their resurgence years away. I doubt this record player was used again until this last weekend, when I asked my father to bring it to me so I could listen to the first-ever record I’d purchased, “1989 (Taylor’s Version)”.

I’d never really been into records. The advent of digital music and streaming made me confused about the hype. Why use old tech to listen to new music?

I decided as I pulled the record out of its sleeve for the first time, gazing at the photos that adorned the cover and the inside, that I wanted to explore the modern vinyl obsession. I needed to know, what was so different about this? Would it sound different? If so, how? Why? Was there something meaningful about owning this specific physical copy? These were the questions I wanted to answer as I listened.

An introduction to 1989

I’ve always appreciated physical media. That was how my listening growing up started.

My brother’s first car, a cherry red 1996 Ford Mustang GT, had a CD player and a cassette player. I remember him creating CD mix-tapes with the Kings of Leon, AC/DC and countless other rock bands for listening to in the car.

And it was my brother, Steven, who introduced me to 1989 when I was 16. I walked into his bedroom one day in 2014 to find him listening to it just weeks after it had been released. I’d been a secret Swifite since I was 11, when Taylor released the album “Fearless”. On my laptop in my bedroom with the door shut, I listened to her hits on YouTube through her music videos and memorized the words through “lyric videos” that were little more than glorified PowerPoints. But I never told anyone about my love for her music.

It was with Steven a year later that I heard “New Romantics” — a song off of the deluxe edition of “1989” — for the first time. The song quickly became, and continues to be, my favorite song ever.

This album is by far my favorite record of hers. That might make certain people think less of me. It is, after all, the pop album that Rolling Stone recently wrote is “the record that made everyone a Swiftie.”

But this album gave me everything. I could listen to Taylor Swift, out loud, as much as I wanted. Steven, my idol, had even given this album his stamp of approval. Almost all of my taste in music up to this point had come through him.

Old Tech. New Music.

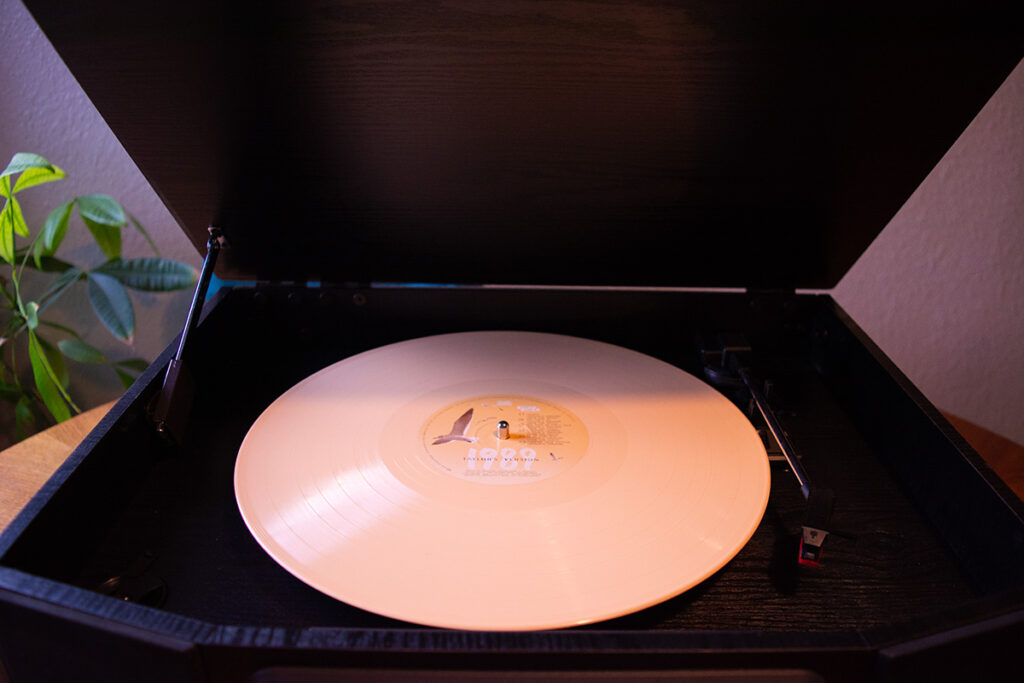

When Taylor Swift announced over the summer that she would be releasing her re-recorded version of 1989, I knew I would be getting it. And I went all out. I bought a T-shirt, a seagull necklace (a motif from the album cover), a cardigan, a CD and the special edition, Target-exclusive tangerine vinyl. I even asked for the album’s matching cassette as a birthday present when my mom called the other day.

All of my new physical media in my possession, I was ready to listen. Saturday morning, my dad brought me the record player and showed me how to use it. The experience was nerve-racking.

Vinyl pressing is a delicacy akin to surgery, and the vinyl’s themselves are more fragile than a crystal wine glass. Dropping a needle onto a record? Terrifying. This is a large part of what confused me so about the vinyl obsession. Why listen to something so easily damaged? I still didn’t understand.

As the disc turned, I could tell something was different. It was likely a bad pressing, which didn’t surprise me. I’d heard from friends that vinyls of her other records weren’t always the best. It seemed to be a Russian Roulette of whether you got a good one.

There were limits to my listening. I couldn’t connect the record player to my surround sound speakers to blast it at full volume. All the player had was a headphone jack that shrieked when I tried connecting it to the auxiliary cord of my sound system. But hey, my neighbors probably appreciated the break from hearing Taylor Swift blaring through the walls.

The background melody sounded mostly fine, but Taylor’s voice sounded wrong. It was sharper, and somehow younger, but it didn’t sound like her, it sounded like someone else. But part of the love of vinyls is the way that they can and do often sound different, unless the music was mixed and mastered specifically for vinyl.

I went from the first disc to the next, thinking about how each song sounded. “All You Had To Do Was Stay” was the best sounding song on Disc One, Side A. “I Wish You Would” and “Wildest Dreams” were the best on Side B. But the songs on Disc Two, Side A were all lackluster, including my beloved “New Romantics.”

So, I flipped over Disc Two for the final run of music. This side would feature the five new songs she’d written for the “Taylor’s Version” of the album. Side B also included a bonus track exclusive to this edition of the vinyl, her rerecording of “Sweeter Than Fiction,” a song she wrote for the 2013 British film “One Chance.”

All of the new songs sounded beautiful, close renditions to the digital versions I’d spent most of the prior 48 hours streaming digitally. “Suburban Legends,” my favorite of the new tracks, was flawless. But once again, there was something wrong the second I got to the final track, “Sweeter Than Fiction.” Like most of the other re-recorded songs, it was flawed. The signature snare drums that open the track sounded out of tune, as did the guitar riffs that soon followed.

I listened to the record again a day later and observed the same issues. And then Sunday afternoon in the car, I flipped to the CD rather than listening through my phone on Bluetooth, and I noticed how, for some reason, the music knocked both the digital and vinyl versions out of the park. It was crisper, cleaner, louder. Every note hit with such specificity. It reminded me of the first “Taylor’s Version” track that was ever released, “Love Story,” which giggly Swifties noted sounded “crispy,” specifically every time she sang “oh” in the lines, “Escape this town for a little while, oh, oh/’Cause you were Romeo, I was a scarlet letter.”

But I needed to be sure that this wasn’t just car acoustics. Cars, in a beautiful way, are built for music. The speakers are close to you, but often lower than your actual ears, so you both feel the vibrations in your body as well as hear them. It’s akin to singing in the shower, where the reverberations can make even the worst singer think they could be Whitney Houston.

I borrowed an external CD drive and slid in my pink 1989 (Taylor’s Version) disc. Playing it took some tinkering. Apple doesn’t make listening to a CD even remotely easy. You’re forced to process the music through the Apple Music app, which then resulted in two different experiences. If I opened the music file like any other file, it sounded like it had in the car.

Yet, when I imported the CD into the Music app, the platform simply gave me access to the digital downloads — which is not what I asked for. It was an infuriating experience, and one that reminds me of how fragile the digital economy is.

Just like how streaming companies — Netflix, Discovery+, Hulu — can’t be trusted to keep even their own content available on their own platforms (HBO Max, I’m looking at you), the tech companies that control our digital listening can’t be trusted either.

CD’s have long been seen as one of the most pristine forms of recording music. My colleague Ryan Wen noted the other day, when CD’s first came on the market, some people thought they were too good, too clear. It was startling to be able to hear the sound of a person’s fingers plucking a string as if they were sitting in front of you.

As I completed this journey that has turned me into a true audiophile, I called Steven once again. He told me about how anytime his wife plays the album, he’ll switch it to one of the hit songs he likes, even if it means catching flack for not embracing the deep cuts. We raged on about the way Apple improperly imported my CD.

And we made plans to listen to the vinyl, the CD and the digital album together, finishing the journey we started together nine years ago when I first heard “Style” as I walked into his bedroom. That’s part of the beauty, I’ve realized, about physical media. It’s something to share, discuss, bond over and gaze at, just like those vinyls hanging above the staircase. .